A MOST VALUABLE PRIZE

A long way from the terrors and fears of the hospital. But not far enough.

Dear Readers,

Thank you for reading The Kureishi Chronicles. I am still unable to use my hands and am writing, via dictation, with the help of my family.

Your contributions go towards my care, which is considerable. If you enjoy my writing, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber.

If you wish to preorder my forthcoming memoir, Shattered, you can do so by following the links provided here:

Splashing through a soaked west London on a moped, a middle-aged man is carrying in his satchel a most valuable prize: a new book.

I am in a wheelchair in my kitchen, being fed coffee through a straw by a pugnacious African woman. I am shouting at my computer screen – scroll up, scroll down, click 59 – which is how I read the newspapers. Isabella sits across the table, rolling a cigarette, telling me to keep my voice down.

Simon, my editor at Hamish Hamilton, charges in, grinning all over. For weeks, Carlo and I have been anticipating this moment: to actually hold the finished copy of Shattered, an account of my year spent in hospital with a spinal cord injury.

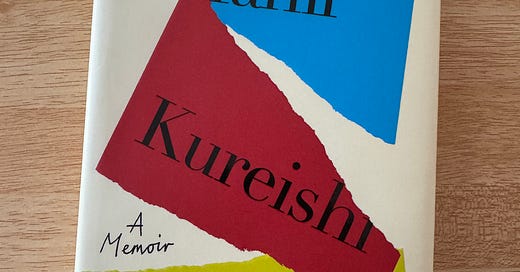

We pass the hardback around between us. It is thicker than I’d imagined; the sleeve is cream, and my name and the title are emblazoned on shards of coloured paper; blue, red and yellow. Of course I can’t handle the book myself, my fingers are still unresponsive, but Carlo turns the pages for me, and we examine the font and margins, afraid to look at any particular line too closely, for fear of spotting mistakes which are too late to revise.

I have published many books over the years, and I remember the excitement of holding my first novel, with its brilliant cover by the great Peter Blake. Naturally, as you publish more regularly, the thrill diminishes. But this time it is different.

Shattered, written in close collaboration with my family, was created in almost unbearable circumstances, across five hospitals and under the strain of a near-death experience. Some of it I barely remember writing, I was so drugged-up and traumatised.

But this finished copy stands for what opportunities trauma may offer. Literature converts suffering into art. Most of the patients in the Hospital of Accidents - as I called the ward in which I stayed - are unable to resume the lives they previously led. If you are a ski instructor, a policeman or a teacher, it is almost impossible for you to work with an injury like mine, although some people continue to lead useful and productive lives. I am one of the lucky ones.

It takes many people to make a book: the cover designer, printer, editor, the friends who read it through, numerous publicists and journalists, as well as the booksellers, who actually get it to the public.

All these people believe in books as an inherent good; that thought, intelligence, and articulation are important to democracy and the quality of our lives.

Tonight, a good friend visits, and we sit around my kitchen table drinking wine and chatting about movies. This friend and I met in the nineties, after he published a book on psychoanalysis, about which, at the time, I was insatiably curious. There was something I wanted to be cured of.

He and I would go to Paris for the weekend, where he’d been a student. We would walk along the Seine talking about psychoanalysis and its relation to popular culture. This was a man who was fascinated by modern hip-hop and Lacan in equal measure. Before these conversations, it hadn’t occurred to me that low-brow commercial culture could be interrogated by sophisticated ideas. The more pulpy and trashy, the more the structure of the contemporary imagination was exposed.

After my accident, he proved to be one of my most loyal and steadfast friends. This is a man who listens to people for a living, from early in the morning, until six o’clock in the evening; complaints, failure, death, impotence, catastrophe. But with me, he remained attentive and concerned. He would say, ‘If you are not helping people, what are you doing with your life?’

After half an hour of good talk, a carer knocks on my front door, and they, with my live-in carer, haul me off to bed, where they check that I am clean, change my clothes and settle me down. It is 7pm.

My dear friend moves from the kitchen to my bedside, feeding me wine and talking about how Freud travelled second class, and Jung first, when they went to the US together in 1909, and how enraged this made Freud. Receiving friends in bed has become my new normal, and it is beautiful in its ordinariness. A long way from the terrors and fears of the hospital. But not far enough.

The next day, in a private hospital on Harley Street, a urologist jams a thick black stick with a camera on its tip down the end of my penis. He shows me the source of my catheter blockages on a monitor. Never mind that I am crying out in pain and blood is now dripping from my penis, he tells me I will need an operation to eliminate some stones and debris.

I am trying my best to move on from the suffering of last year, but I am locked into the medical system, and each time I return to it, I am reminded of how alienated and anonymous it makes me feel, that I am a hostage of my body.

But then I return home. I ask Isabella to show me the book again. It is dedicated to her, For Isabella, and she kisses me on the forehead. The first chapter is titled The Fall, and I read the opening line;

On Boxing Day, in Rome, after taking a comfortable walk to the Piazza del Popolo, followed by a stroll through the Villa Borghese, and then back to the apartment, I had a fall…

Congratulations Team Kureishi. Mighty work.

Congratulations! Even more people will know your story and get to know how you've dealt with what happened, and is still happening.

Besides your talent for writing, what keeps me reading this is your absolute honesty...in a culture of sentimentality, you write about what's not pretty as well as what's beautiful.