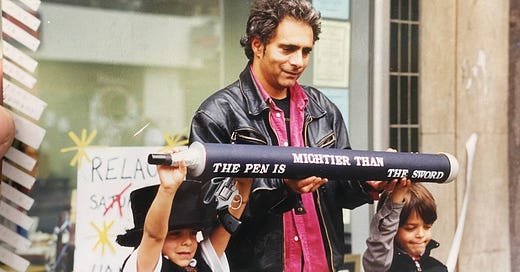

There has barely been a minute of the last ten years that I haven’t enjoyed being with my three sons, Sachin, Carlo and Kier. But I have to admit that the early days were difficult, if not nasty and even hair-raising at times.

I am sure there isn’t a parent in the world who wouldn’t admit this. Freud refers to these strong alternating currents as ambivalence, which does not mean mixed feelings, but absolute hating and absolute loving, often at the same time. The people most likely to madden you are not those you merely hate, but those who raise the greatest, most insane-making conflicts in you.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to THE KUREISHI CHRONICLES to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.