Dear Readers,

As The Kureishi Chronicles hits its nineteenth month, I would like to thank you, my audience, for all your love and attentiveness. With a following of twenty-eight thousand people, we are one of the largest Substacks in the country, and that is down to you.

All my new writing will be freely available; all we ask if that if you have the means, believe in paying for good writing, and want to help with my recovery, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your donations keep this page alive.

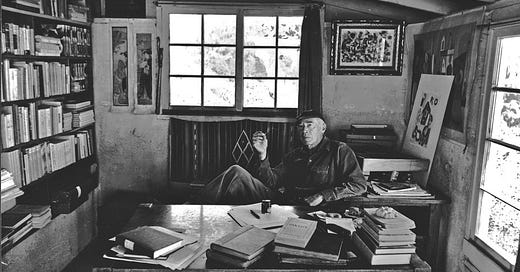

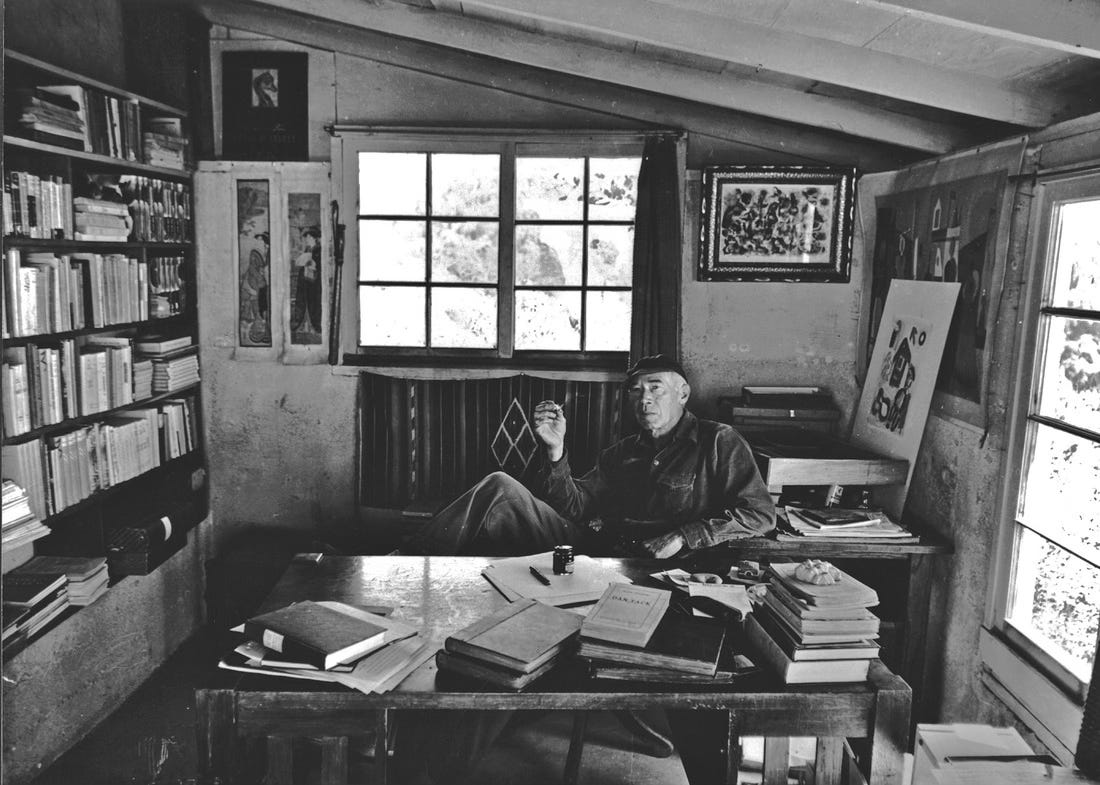

(Photograph of Henry Miller in his office)

In my early twenties, when I became writer in-residence at the Royal Court theatre in Sloane Square, it was taken for granted by the directors that I would teach. I was informed, somewhat casually, that I would run a group each week as part of the Court’s youth theatre.

When I turned up, I was startled to find a group of young adults sitting in a circle looking at me expectantly, as if I was someone who knew what they were doing. Never mind that I hadn’t taught before; or that I was more or less the same age as the students. No one had prepared me for this. I was, as they say, thrown in at the deep end.

But I did have some experience with teaching. I’d been taught by both my father and by an editor at the Anthony Blonde publishing house, Jeremy Trafford. But that was one on one teaching: mostly encouragement from my dad and instruction from Jeremy on the creation of character, which in his view drove all interesting writing.

I was always interested in how stories are created out of elements like plot, structure, suspense, conflict and relationships. How does a writer work on himself to produce and shape ideas? Where do they come from? How do you know whether an idea is a good one? How do you bring it to fruition?

For me writing has always been practical. After all, I began this piece by wanting to write something about teaching but when I started I had only the first couple of sentences. Some people like to plan an entire piece in advance but I’ve never worked that way. Experience has taught me that one idea will produce another idea. Shape will come later.

And so, confronted with a group of twelve young and eager faces, many of them, unfortunately, appearing highly intelligent and from cultured families, I knew I couldn’t bullshit.

We would talk about what we expected from the workshop before beginning on the practical part. It was essential to me that at every workshop the students would produce a piece of writing: it might be the creation of a particular character, a description of a place or a conflict. I would send them away for thirty minutes to a quiet area in the building where they would write something new. There was a time limit, it was high pressure.

The young writers would read out their work and the group would articulate their thoughts. This set the paradigm of how I learned to run workshops; having no idea what other writing teachers would do, I created a space where ideas could be developed by the group. The students began to talk to one another, becoming friends and collaborators, going to each other’s houses. I saw that running a workshop meant standing back, keeping out of the way, allowing it to develop its own energy and momentum.

Later, I was invited to run bigger workshops including weekend courses, or even week-long courses for the Arvon Foundation. These involved longer sessions and more reading. It wasn’t uninteresting to find out what the students were thinking at that time; politically, socially, sexually and so on.

Through this experience, I began to learn what constituted originality, and I become aware of what a small proportion of the work I read was of value. You would spend time with writers who couldn’t improve much; there is a limit beyond which they can’t go.

I no longer run workshops or groups, it’s too tiring and it’s not as effective as working with a single student. But on the other hand, the students do learn from one another. Their competitiveness can be a simulant.

Occasionally, it can become clear to the teacher that what the student is actually doing is exploring some particular part of their history in order to think it through. They wonder what went on in their childhood, with their parents, or whatever. This is writing as therapy.

I had a private student who worked with me on a novel for ten years, and she still doesn’t appear to have got anywhere close to finishing it. I wonder now if she was ever really serious about writing the book at all, and why she kept on seeing me. I suspect she enjoyed our conversation, and that the project was therapy by other means.

You cannot exhaust an analysis of your childhood. There is always more to go over, and another way to see things. So, for people who don’t believe they need therapy, writing is a place where they can find out about themselves. After all, writing can be as useful as a dream when it comes to exposing the unconscious. You are there without knowing it.

As a reader I might see things in a student’s work, and therefore in their life, that they were unable to see themselves; I can suggest connections or even truths which may not have occurred to them. These points have to be said at the right moment, when the subject is on the verge of discovering them. You are not the expert of their life.

I teach a young woman now who is talented and her work is strange, evocative and original. I’ve never read anything like it. Many students, even the good ones, tend to follow some kind of formula. They want to write like other people. But this woman is so original it is difficult to know what to say to her. I mostly listen while she tells me what she is doing. I guess my job is to respond in an authentic way. But this is unusual. Most writers need a lot of advice both about their work and the market.

I like working side by side with a student as they cut and rearrange their work to make it more effective. I am their editor and can be a motivator. It’s cheering to see writers improve or to read those who have an original point of view. It reminds me of what I enjoy about reading and others’ creativity.

One of things you might have to do as a teacher is disillusion the student: by this I mean inform them what hard work and commitment – in terms of time and energy – it takes to write a book. It is not a breeze; there will be a lot of frustration to bear, and a lot of rewriting to do, some of which is tedious and exasperating. The chances are that no one will ever read or appreciate your work, so it must be done for its own sake, which is always the best way to do it.

The most frustrating students are the ones who you might call ‘semi-talented.’ They have good ideas and can write a bit, but never reach the standard of publication. I’ve had several students like this, and I wonder what happened to them.

During the time that I’ve been teaching there’s been an eruption of creative writing courses: particularly in universities in the United States but also here in Britain as well as in Europe. It is a neoliberal idea that you can improve or even purchase talent.

On occasion, I have been sent students who are barely proficient in English, let alone able to produce a substantial piece in that language. The colleges are more interested in accruing the wealth of overseas students than in producing quality writing.

If you think of the writers throughout history you have admired, you will find that none of them from, say, Sophocles to J.K. Rowling, actually attended created writing courses. This isn’t to say that these writers haven’t been taught. Presumably they would have read a lot, or shared their work with intelligent friends, editors and other encouragers. But this formalisation of writing has always had something absurd about it.

I still like to teach but I’ve always found it meaningless when I am supposed to give the students a mark or even a degree. It useless to point out to the authorities that giving a student a B+ is neither here nor there. What makes a writer a real writer is that they begin to find an audience for their work; readers who are excited by what they find on the page.

This isn’t to say that it impossible to teach. If anything, creative writing courses do enable writers who are starting out to make contact with readers who know how to talk about texts. A pithy intervention can really help someone.

Someone once said that at least one in five people are writing a novel. I barely know anyone who isn’t. It is still a prestigious form. And so, despite social media – the junk food of communication – literature continues to adapt to the contemporary mood. Where there is digital overload, people are returning to this more relaxed, nutritious analogue mode - reading words on a page.

Reading a great novel like Middlemarch – the minute exploration of class, character and society - is both demanding and time consuming, but in its depth and forensic analysis, it goes further than anything the media can do today.

The return to the novel is not unlike the present rebellion against late-capitalism’s production of trash; junk food, junk pop, cheap clothing and electronics, barren hook-ups. The age of kitsch and synthetic bargains is over; we are experiencing a necessary correction, people want that which is authentic, lasting and real.

If you would like to preorder Shattered, you can do so on Amazon here.

I was a teacher for 33 years. Writing was always the hardest and the most interesting thing to teach. When teaching writing, you feel more like a coach. I didn't presume that I was better at this thing...just older and more experienced. My job was to listen, to elicit what the writer's goals were, to provide suggestions (if desired), to provoke more thought. Ultimately, the writer had to work through the process.

Recently a video by a 1990s, Washington DC-based band called Velocity Girl washed up in my YouTube subscription feed. When I delved into the reasons why a 30-year-old song had suddenly surfaced among the shark footage and the creepypasta greentext (purportedly true supernatural tales sketched out in disjointed sentences), I discovered that Sub Pop records were poised to re-release the first Velocity Girl record - Copacetic.

I like about half of Copacetic and find the other half irritating. The fifty-percent of the record that I do like, I like a great deal. The first song I heard from it - Crazy Town - seems to me fully-realised, in that it achieves what it sets out to do and I can't think of any way that it could be improved without upsetting the creative balance. Evidently the band disagree with me on this point as the reissue of Copacetic is an overhaul of the original mix; an attempt to present the songs as they wanted them to sound, while adhering to a 1990s aesthetic.

Copacetic was originally produced by Bob Weston. I like Weston. He keeps it real as an engineer and as a musician. In the promotional spiel for the reissue/remix of the album, the band diplomatically state that he did exactly what was asked of him and that it was their inexperience in the studio that resulted in the record falling short of their expectations. In the wake of reading this, I pondered the role of the record producer. It is one of those dark arts, I would think similar to teaching writing: There is a band/artist who has a creative vision, but who may be uncertain of how to get from A to B. It is possible that they cannot even articulate what they are trying to achieve, as it exists beyond words. In these cases, it is the job of the producer to identify what the artist is aiming for and to assist them in homing in on it.

Some producers are very hands on. Brian Eno's fingerprints are all over the albums he works on. I doubt that Coldplay would have made the leap of faith that was necessary to write 'Viva la Vida or Death and All His Friends' without his encouragement. They recorded an album that sounds like a cache of hitherto unknown William Blake poems set to music; songs that embody nativity, joy and hopefulness in a way that is almost religious.

Other producers are more hands off. Steve Albini, who died recently, regarded himself more as an engineer. He would meticulously set up the studio to best capture the sound of a band, but wouldn't directly involve himself in the creative process. He wouldn't stop a band from pursuing a bad idea, but he would make it very clear that he thought that it was a bad idea. Luke Haines, formerly of The Auteurs, recalled Albini's silent imitation of a hippie taking a long drag on a joint while a tossing a Frisbee, that he would enact whenever he felt that the band were veering off-course. This condemnation, delivered sarcastically through the medium of mime, was enough to rein them in.

When producers fail to understand what makes a band good, it can be an outright disaster. During the 1990s, there was a local metalcore band called Above All who seemed to be poised on the brink of success. I am not really into hardcore - a lot of it strikes me as performative rage underscored by metronomic finger-wagging. Having said that, I did like the energy of Above All's live shows. They signed to Roadrunner records which was huge. It should have been the beginning of a career. I remember listening to their over-produced first album and thinking 'they've blown it'. All of the rawness was gone. All that a producer needed to do with that band was get them riled up over the state of the world and then let them loose, and get as much of that energy down on tape as possible.

The thing that made me want to write novels was an offhand remark made by Henry Rollins regarding his book 'Get In the Van' - his account of touring with Black Flag during the 1980s. He said that, when he started assembling material for the book, he knew that, a year hence, he would still be working on it. I wanted that for myself; that big project. Also, by then I knew I wasn't going to make any headway in mainstream publishing. The only other option was to self-publish. I wrote a short novel about the spiritual journey of an atheist and released it through Amazon. In a month, with no planning or research, I wrote a 60,000 word espionage novel set in the Soviet Union of the 1980s. I wrote almost 300 pages of chapter and character notes for a novel concerning an African community in Hammersmith that is facing a crisis of leadership. I was about to begin writing it when I was temporarily kicked off of Amazon for reasons that remain unclear. Afterwards, I didn't have the heart to go back to the book.

At present I am eye-deep in a psychedelic pirate novel. It is a very ambitious story and I have certainly bitten off way more than I can chew. There is a massive cast of characters. On two occasions, the narrative pivots significantly. A few people might read it. However, the real value of a project to me lies in the process - the writing of it, the editing of it, the designing of the cover, the getting of it out into the real world.

On the wall of our home there is piece of framed Jesus-themed embroidery dating to 1882. It was stitched by a 13-year-old girl named Emma Cornish, who is a distant ancestor. According to our family tree, Emma died a spinster, which is where Jesus-themed embroidery will get you. Her needlework is probably the only remaining part of her left in this world. It is her statement that says 'this is who I was'. If a handful of over-ambitious paperback novels, of somewhat questionable quality, legally deposited in the British Library, are all that will remain of me long after I am gone, then I will be happy with that.