Dear Readers,

My dispatches will always be free and open to everyone. If you have the means, and believe in paying for good writing, please do become a paid subscriber. Your contributions go towards my care, which includes physio, massages, hydrotherapy and equipment, all of which is essential for my physical maintenance.

Love to you all,

Hanif

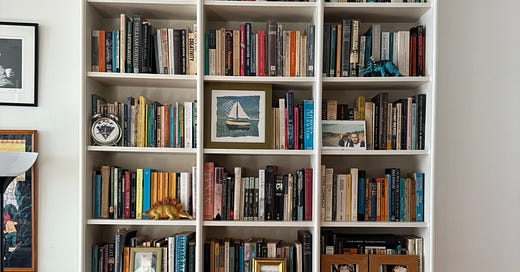

I live, work and sleep in my living room between two floor-length bookshelves which, before my accident, I rarely looked at. Now, as I lie in bed being washed or changed, or when I am sitting in my wheelchair having my splints put on, I can’t help but observe these books. When and where did I buy them? When did I read them? What do I remember of them? And why do I have three copies of Eros and Civilisation?

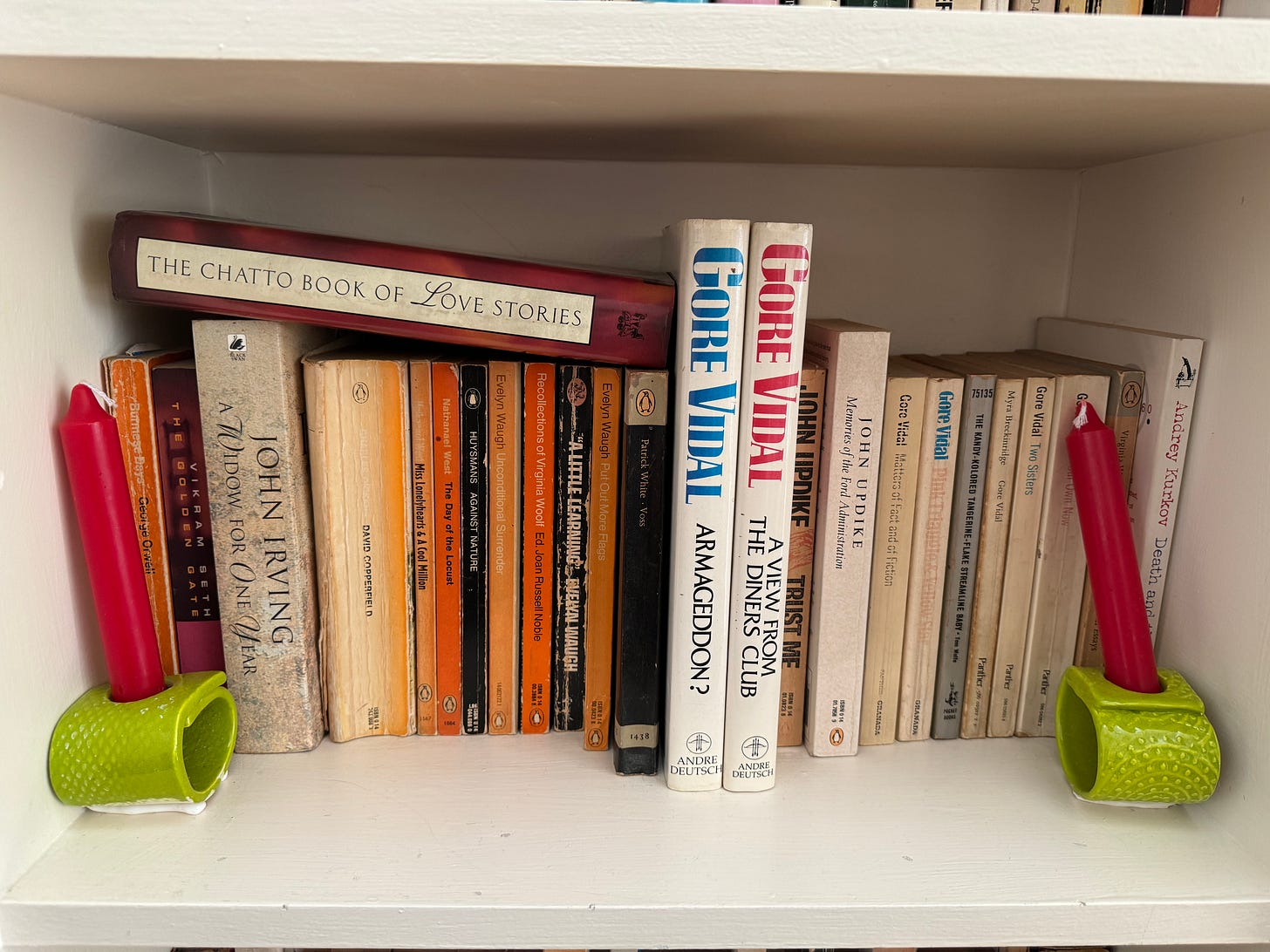

When I moved into this house at the end of the nineties, I had these shelves built, and filled them more or less at random with paperbacks from my previous flat. They are mostly fiction from the sixties and seventies. At eye level, I can see a lot of Updike, Gore Vidal, Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh. It’s unlikely I’ll ever read these writers again since I am unable to hold a book. Yet I’m reluctant to dump these volumes. I always wanted to have a library, a permanent collection which I could use for research and browsing, but the internet has made this necessity somewhat redundant.

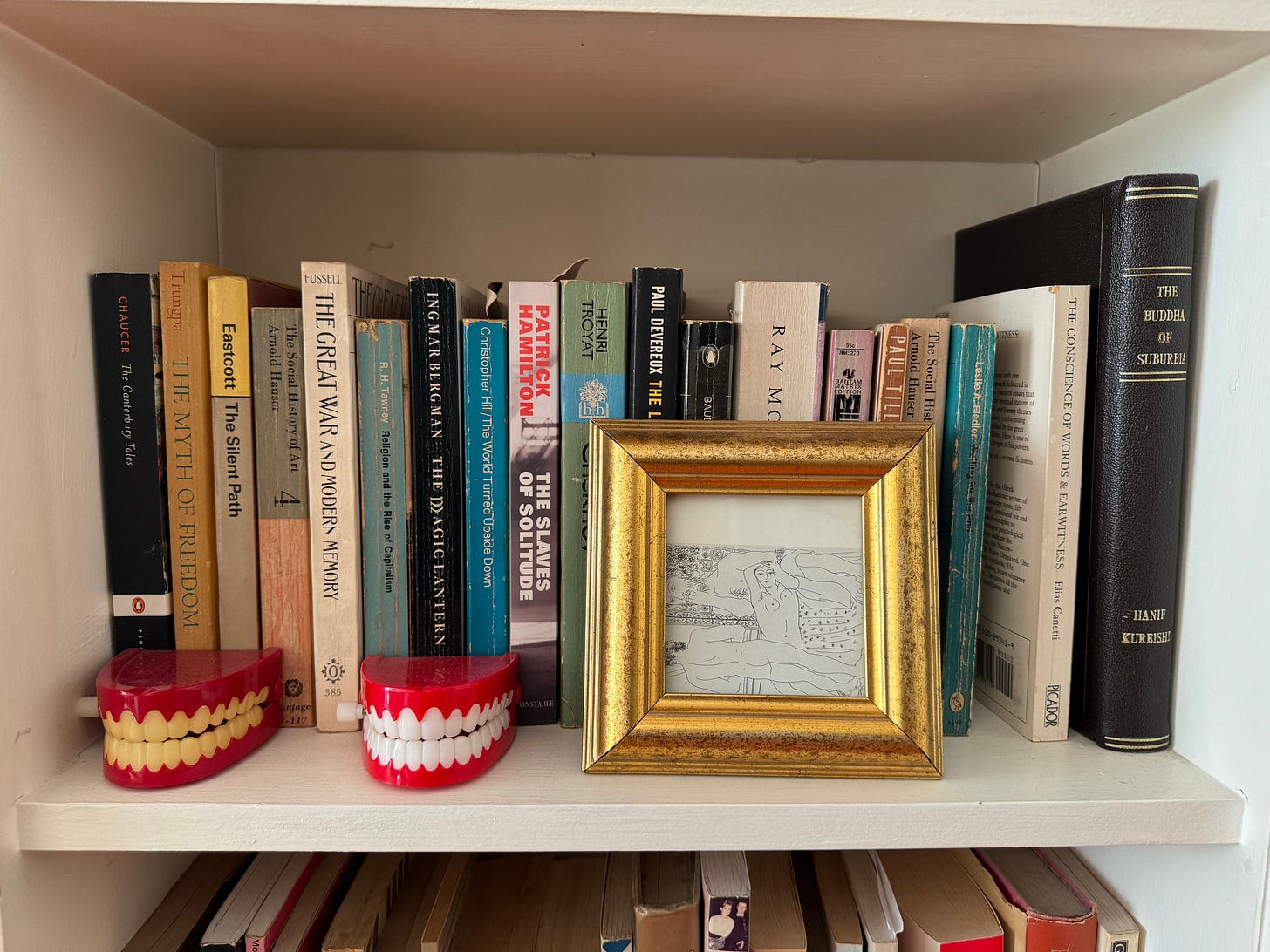

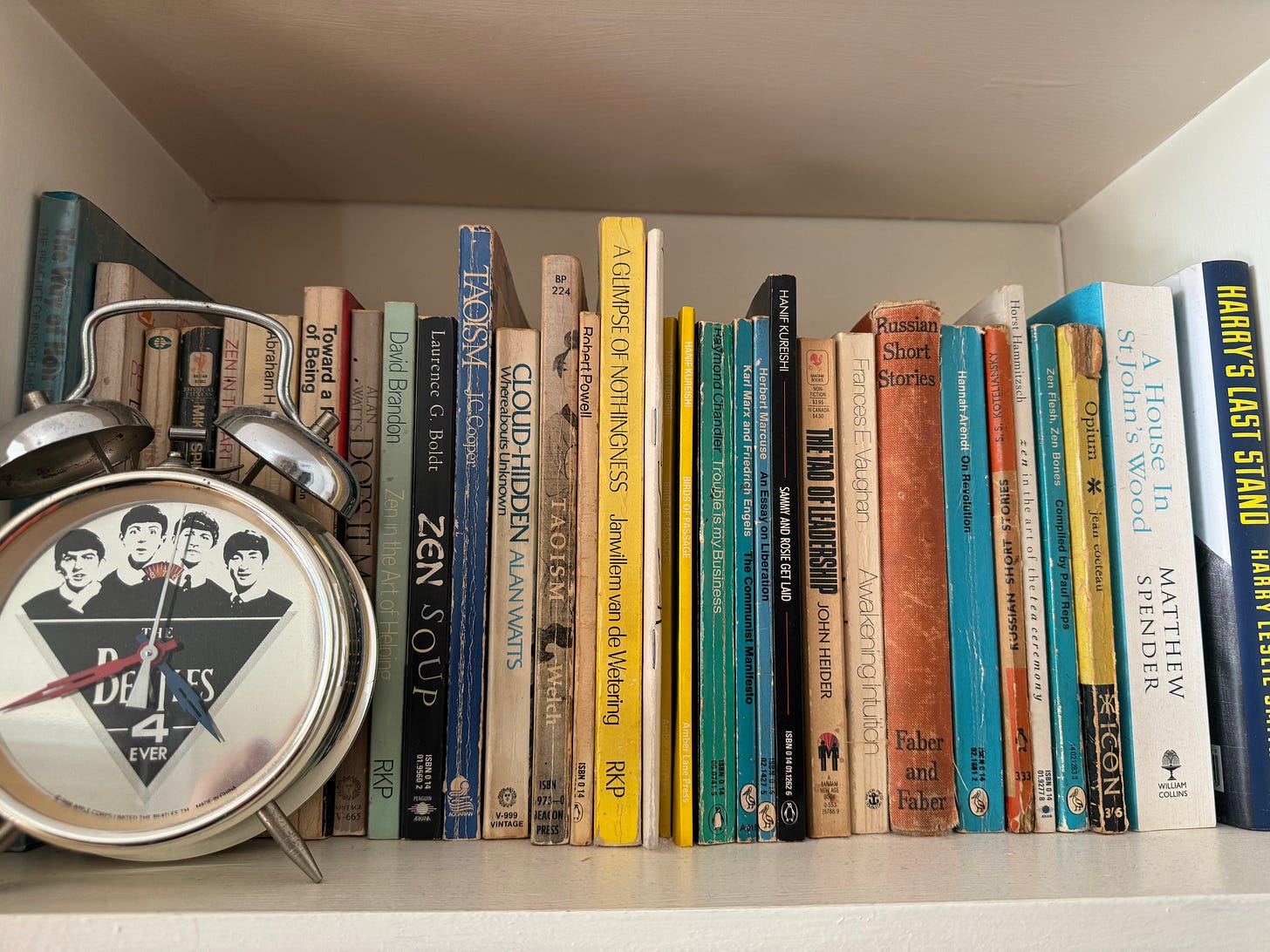

On the bottom shelf there is some heavier stuff: Marxism, philosophy and post-modernism. To my right, next to the bed, there are books about Zen and the counterculture, as well as volumes by Alan Watts, the Buddhist author and promoter of Eastern culture, who was brought up, coincidentally enough, in Chislehurst, just outside Bromley. I wonder whether if he will ever come back into fashion – such an interesting figure.

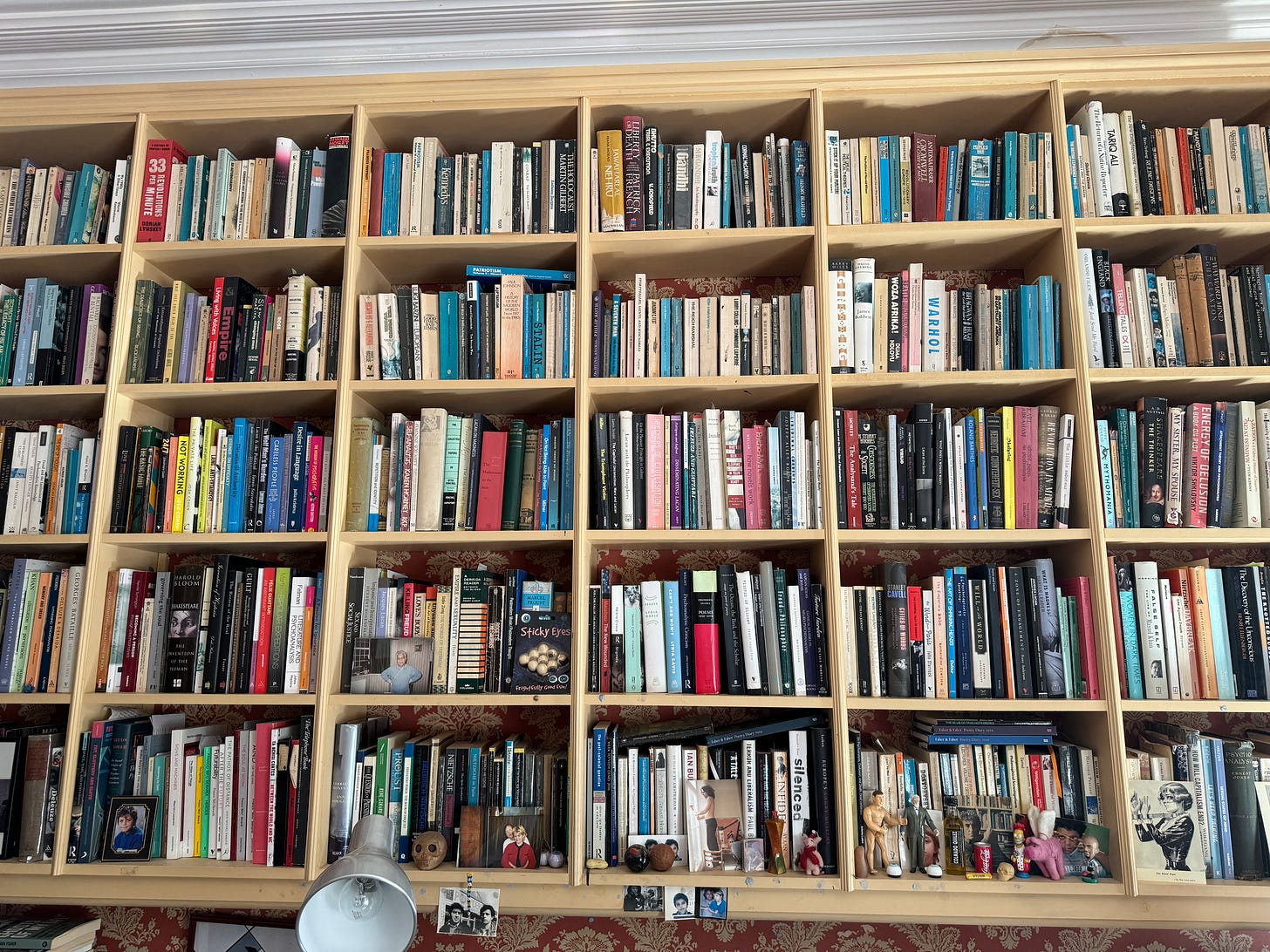

My sprawling psychoanalytic library is upstairs in my study, and is organised in order of author, Freud, Klein, Winnicott, Lacan, Phillips and Leader. On the other side of the room, there are three shelves of creative writing books, which I continue to collect but rarely read. Anyhow, I can’t get up to my study now. Sometimes I sit at the bottom of the stairs looking up, wondering why I can’t just step out of this chair and float up to my study as I used to.

Occasionally, when people come to the house to fix things, they say, almost in wonder, “You’ve got a lot of books, have you read them all?” I always say, “I’ve started a lot of them.”

There were several second-hand book shops in Bromley in the sixties. As a child, I spent many hours accompanying my father to them. He would clamber up ladders, stand on stools, venture into basements, emerging with armfuls of old Penguins and rotting hardbacks. I’ve always followed dad in this pursuit, and London in the seventies was still full of second hand-bookstores, where one could burrow for hours and pick up interesting stuff cheaply.

Obtaining books was a pursuit that my dad had in common with at least two of his brothers, who were called, in those days, ‘intellectuals’ - not a word you hear often now. Indian men influenced by Bertrand Russel, George Bernard Shaw, R. H. Tawney and other leftist and liberal writers of the time. These uncles would read political theory, Marxism in particular – which was a live idea then - as well as the great nineteenth century writers in translation, Balzac and Zola were favourites. When my father and I visited my uncles at home, we would look through their libraries, dad’s head at an angle, examining the spines, and the men would swap and borrow books.

There is something charming and triumphant about finding a book you’ve longed for in a second-hand book shop, though these days it is easy to get anything you want from Amazon or Abe books. In the seventies and early eighties, when I was living in Baron’s Court Road with my then girlfriend Salley, we began to tour these shops in Gloucester Road, Putney and Chiswick. We sought out books on the burgeoning new media, on race, feminism and American psychology; Maslow, Rogers, Perles, Wilhem Reich and Marcuse. I used to read all the time, on the tube, on the toilet, in waiting rooms and in bed, trying never to be bored, a condition which reminded me of my childhood, but mostly, I read to further my education.

None of my three sons read for pleasure growing up. They had Xbox’s, Playstations, a Wii, TV and movies. I always considered reading to be serious, and television and games to be frivolous. Kier is dyslexic and has never had an interest in newspapers or contemporary events. He barely knows who the Prime Minister is. He doesn’t want to know what is going on. It might be that he has rebelled against my passions, but Carlo and Sachin have embraced them.

It seems strange to me to be disconnected from the politics and culture of the country you are living in. In the various hospitals I was in, the nurses told me they didn’t have time to read the papers or watch the TV news, and had no opinions on the contemporary scene, except that it was depressing.

To my relief, Sachin and Carlo began to read and borrow books from me when they were sixteen or seventeen, and now both have decent libraries of their own. Carlo, who was educated privately, says that he began to read because he became aware that you could only outsmart your peers if you read beyond the curriculum. My reasons for reading were different, they were to do with class. If you came from a lower middle-class background, the schools were rough and inadequate, and you would be competing, for the rest of your life, with privately educated middle-class kids. Reading was a necessary attempt to improve my social status. When I moved from the suburbs to London, and began to work in the theatre, film, television and publishing, those worlds were dominated by white Oxbridge educated men. As an interloper, if you were to succeed, you’d have to make sure you had something different or special to impress with. I knew little about history or music or even the empire, but I could write about the new multicultural Britain.

In the pub next to the Royal Court, I would hear directors talking about composers or music. Retaining what they mentioned, I would go out the next day and buy the work of the artists. Wanting to keep up, if someone cited a novel of interest, I would make a note, read it and think about it seriously. Among the many deficits of class is the idea that you, having had a weaker education than the imagined other, will always know less, and should therefore buttress yourself with wide and significant autodidactic education.

It is essential that there is a relation between writing and reading, where reading stimulates and educates, particularly at a young age. Admiration is important; it’s from other writers that you can filch ideas about plot, storytelling, voice, dialogue, character, and the rest. Other writers’ work is a resource from which you can develop yourself.

When it comes to my writing, I’m in a regular routine and more cheerful than I have been for a while. But as I write this sentence, I become aware that I am urinating in my pants, something that shouldn’t happen if my catheter is working correctly. Ten minutes later my carer, with the help of Carlo, has put me into the sling, like a large baby, and hoisted me back onto the bed to be checked and changed. Work will have to be postponed for thirty-five minutes. It is quite a procedure. I have to be rolled while my pants are taken off and my catheter tube - which runs from a hole in my stomach to my leg bag – is checked. I’m staring at my paperbacks again, George Simenon, Simone de Beauvoir and Henry Miller, their names keep me sane as I go through this daily humiliation.

In the mornings, when everything is running as it should, I work on Shattered, which is almost finished, as well as the blogs, of which I usually have several in mind. I work on them simultaneously in my head, until I feel they are ready to be explored and expressed. There are many sources of inspiration: conversations with my analyst, with the boys and Isabella, my memories and my current quandary. Each time I write something I wonder if I have said enough, and then a few days later something new occurs to me. I have been writing long enough now to know that this is the ‘process.’

David Bowie told me he always had music running through his head, he was continuously working on something. It was an off-hand remark, but a profound one, particularly as he was so prolific as an artist. I wonder, though, whether this is the case with most artists, that there is always a tune or an idea present in their head, percolating.

An idea always percolating? What a productive way to think about it. I’ve always felt I was great about idea-generating, but dreadful about carrying through. Hmm. Thank you. I’m looking forward to buying Shattered.

Great piece Hanif. I remember the Southwoid bookshop near Highgate station with great affection. Books will never go away! Even when urinating in one’s pants. Which is the next phase as far as I am concerned. Love Nige