Dear Readers,

My dispatches will always be free and open to everyone. If you have the means, and believe in paying for good writing, please do become a paid subscriber. Your contributions go towards my care, which include physio, massages, hydrotherapy and equipment, all of which is essential for my physical maintenance.

Love to you all,

Hanif

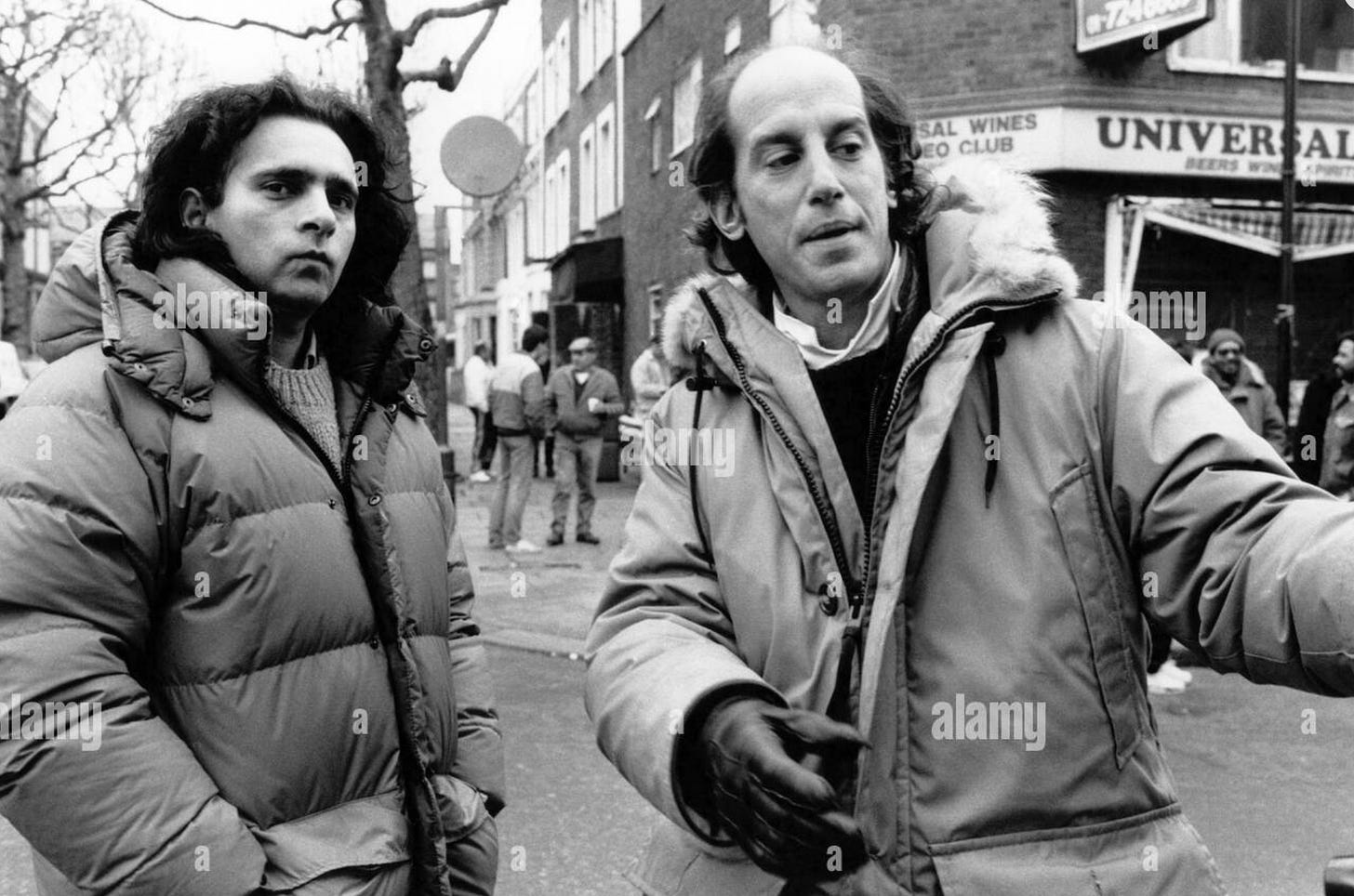

In the late 1980s I directed a movie. I was given a chance by Working Title Films to work on a story with good actors but a small budget. It wasn’t uncommon for writers to become directors - that was often the pathway.

I had a brilliant cinematographer, Ed Lachman, and a good producer. London Kills Me (1991) was set in Notting Hill as it was being gentrified. I had spent a lot of time in the area, around the Portobello road, and was enthralled by its decadence, its mix of races and classes, lawlessness and creativity. The rich were beginning to move in because the houses, many still semi-derelict after the war, were magnificent.

The movie concerned a poor kid, a small-time drug dealer, and his gang of friends, who were squatting in a gangster’s pad, and their adventures as they tried to survive in the new hyper-capitalistic environment.

Turning up on the first day in a warm coat, so nervous I could barely breathe, I was faced with a barrage of questions, ones I was unused to as a writer: questions about the set dressing, about costumes, lenses and lighting. Having worked previously with Stephen Frears, and seen how effortlessly he had dealt with all this, and how at home on a movie set he was, I soon became aware that that wasn’t the case with me. Things would get worse.

When I started writing seriously as a teenager, I began with novels because they were what I’d read as a child.

We rarely went to the movies or theatre; we did of course watch television, but I never associated these forms with writing. Or with serious writing, or art.

I must have been lonely or something, or it was possibly the influence of my A-level college experience, but in my late teens I began to write for the theatre.

My A-level English class was taken to the Aldwych to see Jean Genet’s great play The Balcony, and I found myself enthralled by its mixture of depravity, corruption and beauty. I wanted to be doing this.

Many of my friends were in bands, rehearsing in Bromley garages. Following David Bowie, our exemplar, they had begun to experiment with costume and theatricality. I yearned for this myself, for collaborators who would be more mature, experienced and with better ideas. Not being able to play an instrument, the theatre, which was very lively in London, was the closest I could get to being in a band.

Soaking the Heat, my first play, was given what was called a Sunday night production, at the Royal Court’s the Theatre Upstairs, directed by David Halliwell. This was the beginning of my involvement with the Royal Court.

Antonia Bird, who was one of the young directors there - along with Roger Michel and Danny Boyle - was the first I worked with. I had written a lunch-time play, The King and Me, about a working-class Elvis impersonator. It was with Antonia, who later directed many television plays, but died young, that I began to figure out what the writer’s relation with a director should be.

As soon as we started work, it was obvious that she was in charge, and sitting there in rehearsals, I began to wonder about how much I could contribute to the process. What might I say to the actors without interfering with the director’s authority? How much should I be present at rehearsals? What if I didn’t like what the director was saying or doing? Was I really needed?

I began to worry. I had handed my writing to someone with their own ideas about what the piece should look and sound like. After all, the director would cast it, decide where the actors stand on the stage, and how they would say their lines. They would determine how it will be designed, what the costumes were, and how it would be lit. That is a lot. And you would begin to realise, during rehearsal, that this little piece which emerged from your life, and you wrote in your bedroom, is transitioning into something else. You are losing control, and this can be an exciting or disappointing experience. Or most often a bit of both. From now on, you are a backseat driver, and it can feel like the play no longer belongs to you. You will wonder if you will get it back.

Trying to find my way during the first few days of filming London Kills Me was mind boggling. Film is expensive, every moment counts. I wanted to experiment, try new ways of doing things, putting the camera in unusual places. As a writer you are entirely free, you can go wherever your imagination takes you. Filmmaking is practical. I was forced to think about the budget, the availability of the actors, and the fact that it snowed on several days. I couldn’t sleep, I was on edge the whole time.

Some directors will listen to you, will be interested in what you say, and will try to integrate your ideas; others will not want you around after the initial discussions, ‘sniping from the side-lines’, as one director put it. After all, like you, he or she has spent years learning their craft. They may feel affronted by someone telling them how to do their job, despite recognising that work began with you.

A significant director in terms of my development and career was Max Stafford-Clark, at the Royal Court Theatre. Max, the artistic director, asked me – an inexperienced writer in his mid-twenties - to write a play about immigration and the new arrivals from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Max was a boss, he was authoritative, talented, charismatic, and knew what he was doing. He was a great teacher for me, giving astute notes, and often direct instructions. He was demanding and tough to work for, which is what I needed. I knew, and he realised, I could be lazy with my writing, hoping to get away with things that were weak. But he believed in me and my talent, pushing me to do better.

With this new play, Borderline, I felt I was beginning to find my voice as a writer. Max was good on comedy, encouraging me in that direction, as well as insisting the piece be serious, political and contemporary.

He would interrogate every line of dialogue in every scene. What were these words doing? Was it dynamic, did it drive the piece forward, could it be reduced or cut entirely, with the story still making sense? He would slash through stuff that had taken me hours to write. It was horrifying to kill my darlings, and an important lesson.

I didn’t have time to sulk, my preferred method of passive aggression. In rehearsal, I had to be alert, sitting there with my notepad, constantly rewriting as the actors went through the scenes and complained that they needed more lines or jokes. Max made me aware that dialogue has to work in front of 400 people who have paid to hear it, and it’s only when you hear a good actor reading it that you know whether it works or not. You are terrifyingly exposed. The pressure is enormous.

It was Max’s job to keep me buoyant, but he could become bad tempered. He would shut me in a dressing room until I had rewritten a scene the way he liked it. He insisted the direction could only be as good as the script, and he wanted to ensure he was driving a Rolls Royce.

This experience served me well when it came to working with Stephen Frears on the film My Beautiful Launderette two years later. Stephen had worked at the Royal Court, trained by the great Lindsay Anderson. Stephen admired writers, and knew, too, that his work was dependent on the quality of the script. My Beautiful Laundrette was low budget, and shot in South London. Stephen wanted me on set the entire time as a consultant, asking me whether the characters really would do or say this or that. Was it believable?

Years later when I worked with Roger Michell he had a different attitude. The script had to be complete before we started shooting. His working day had been worked out in advance; he didn’t want any last-minute rewrites which might upset the actors or waste time; he didn’t want me on the set staring at him, putting him off, as he said.

By the end Roger and I had become competitive; he even figured he was a writer too, and could do the adjustments and rewrites himself, infuriating me. I was experienced enough now to know where the line between writer and director should be drawn, and that when it was crossed it wouldn’t help the piece.

Patrice Chéreau also had no intention of allowing me on set. I didn’t write the script for his film, Intimacy, which was based on my novel and some of my short stories. But Patrice and I did spend a lot of time together in London and Paris, getting to know one another, discussing our histories, and thinking about the idea which concerned alienation and sexuality. He was highly intelligent, very gossipy when it came to sex, and good company. But he had his own writer.

I knew I could have done a better job – I would have at least included one joke – but he wanted to work in French and then have the script translated into English, which is why the dialogue doesn’t sound quite right.

I became aware, working on London Kills Me,

the extent to which a writer is used to working alone, in his or her solitude. During filming, I found myself in the middle of a hurricane, organising a large group of demanding people. I had to make fast and difficult decisions. But I am not naturally a leader, a captain or organiser; I had never hired or fired anyone.

Actors are human beings unfortunately; one actor, as I began to direct him, told me that he had punched his wife for the first time the previous evening, and that his family was in meltdown. Another actor told me he was in the middle of an intervention with his drug addict son. Some of the actors and crew were sleeping together. None of this was my problem, but it was becoming so. I’d rather have been at home.

Relationships with directors have been some of the most enriching of my life, enabling me to do something I couldn’t have done alone. A remarkable and inspiring alchemy can emerge from a union of complementary imaginations. It’s sex without touching.

Welcome back Hanif, from whatever it is that has preoccupied your attention.

It is a worry when the signal of someone with a reliable Internet presence and known health issues abruptly vanishes from the online spectrum. Thereafter you hope that their name won't turn up on the Explore tab of Twitter / X, which in general points either towards death or scandal, or a coincidental sharing of a surname with a Premier League footballer.

In a different life, under a different name, I would submit short stories to an event that existed at the time in London, New York and Hong Kong. There had been other incarnations that had come and gone but these were the three that were active. Occasionally something that I wrote would be accepted and an actor would give a performative reading. In a coup that was eventually stymied by the postponement of the New York event, I once managed to get three stories accepted for performance at the three different events in the same month. In my own quiet way I had gone international. It has been all downhill since then, but if that is the peak then I can live with it.

My involvement in these events began and ended with the writing. What the organiser/director and the chosen actor did with the piece was entirely their business. I liked the surrendering of creative control. I didn't think that I would, but I did. My stories were works of imagination. I wonder whether I would have been less willing to let them go if they had been penned from lived experience.

I made a point of attending the London events where I sat out of the way and made a mental note of what worked and what didn't. In terms of shining a bright light on your fuck ups, there is nothing quite like hearing your writing read back to you by somebody who knows what they are doing. Sometimes it was obvious that the actor had an interpretation of a character or a scene that differed from my own. I found that flattering; the suggestion that something I had created had a life beyond my own conception of it, and dimensions that had not been obvious to me but were apparent to others.

I had the ideal editorial experience working on the Hong Kong story. Very to the point notes – what is the function of this character? Is this sentence redundant? I appreciated that directed focus, guided by insight. I was able to work with that, bring the piece back under the word count and then go another round. I've never had any problems killing my darlings. When I am done writing this I will go back to gutting the short story that I am working on in the hope of making it more tonal. I am throwing away so much.

Reading your account of working in the theatre and on movies cements the idea that creative collaborations work best when the roles are clearly defined in advance. When the lines are not clear, or are blurred, or are shifted at the behest of one party, then it seldom bodes well.

This was fascinating for me to read as I write picture books. I have to hand my story over to illustrators, so know the feeling well of handing your work over to someone else's interpretation. At first, I found it threatening. But then I came to really enjoy what another creative mind and talent saw in the story. In the world of picture books, a good artist and art director create at least half the experience for the reader.