Dear Loyal Reader,

You are keeping me alive. Your interest in my weekly ramblings have given me a reason to go on. I thank you from the bottom of my heart.

I want to continue sharing my progress with you. You are on this journey as well. I kindly ask that if you have the means, it would mean a great deal if could support my writing by becoming a paid subscriber, and keep this show on the road.

Your loving writer, Hanif

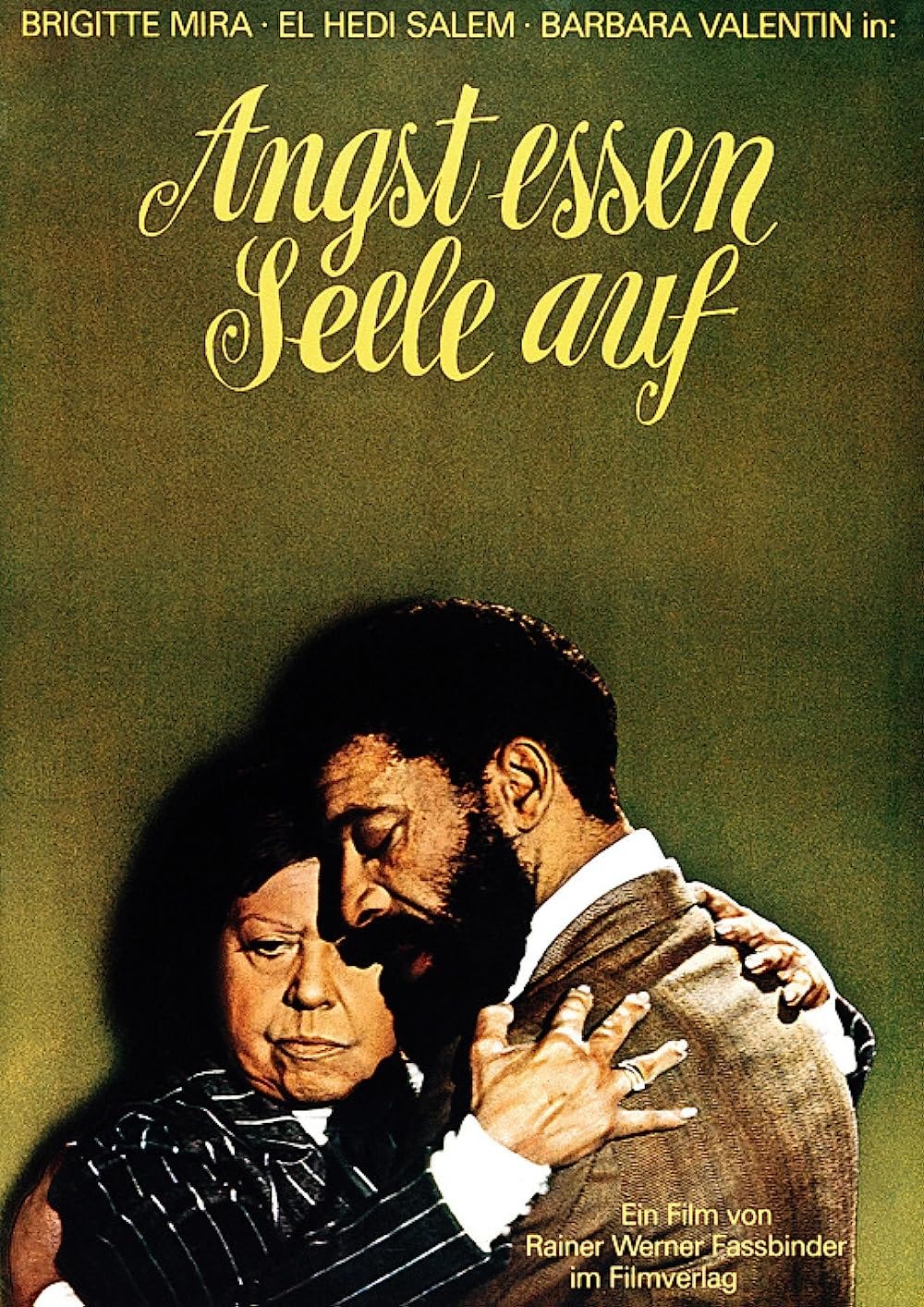

In 1974 the renowned and often notorious young German director Rainer Fassbinder made a simple and relatively small film set mostly in a Munich bar and an apartment. This modest but resonant piece concerns the relationship between a late-middle-aged cleaning woman, Emmi, and Ali, a Moroccan immigrant she meets and dances with in a bar near her flat after a thunderstorm.

I can't have seen Fear Eats the Soul until the early 1980s, when I suspect that though it might be quite different in its details, it reminded me of the relationship between my parents. (The film could easily have been set in any British town.) Although Britain and other European countries were changing rapidly in terms of their racial identity, I wasn't aware of any other films about European racism or 'integration', and this film seemed to be saying something important and necessary.

Fassbinder was an extremely imaginative artist with his own somewhat peculiar preoccupations; however, there are few directors as aware of their time and place as him. He was born at the end of the war and became obsessed with its consequences, making films with women at the centre of them. (He had many relationships with actresses, as well as with men.) Fassbinder resembles Brecht in his ability to combine political analysis with a passion for understanding women. Like Brecht he wanted to see the centre from the position of the outsider; that way he could speak the forbidden. The dignified presence of El Hedi ben Salem as Ali - a lover of Fassbinder, who hanged himself in a French prison just before the director's last film, Querelle, was released - can only remind us of how few black and Asian actors appeared in the great European cinema of the 6os and 70s.

Fear Eats the Soul is not over- aestheticised; the camera barely moves and the actors are often impassive. Nor is Fassbinder much interested in the psychology of the characters. It is their social situation which compels him. Haunted by the recent past, the 1070s were certainly violent and disruptive in Germany. Early on in the film Emmi admits that she and her mother were both in the Nazi party. Nonetheless, she likes Ali instantly and he spends the night in her flat. (Usually he shares a room with six other ‘guest-workers’.) 'Come on,' Emmi says to Ali on the stairs. ‘We’re all forever saying "but”. And everything stays the same.’

'Arabs with Germans not good’, Ali warns her. 'Arabs not human in Germany’. What Fassbinder then explores is the traumatic impact of this disconcerting love on those around the couple, including her children. Emmi's neighbours and friends even begin to suspect her of not being one of them; they point out that her name - Kurowski - sounds foreign. Her workmates say of the ‘Gastarbeiter’, dirty pigs the lot of them. The way they live. Whole families in a single room. All they're after is money. The women who go with them are whores.’

Ali is dignified, impeccably polite and good-looking, though he is no saint. He also appears somewhat isolated, if not lonely. As as a ‘guestworker' he is not a German citizen and seems stranded far from home. We never see he and Emmi making love, but they like to talk. Fassbinder might have been known for his exploration of sexuality and its instability, but this is a love story. These two people really like one another.

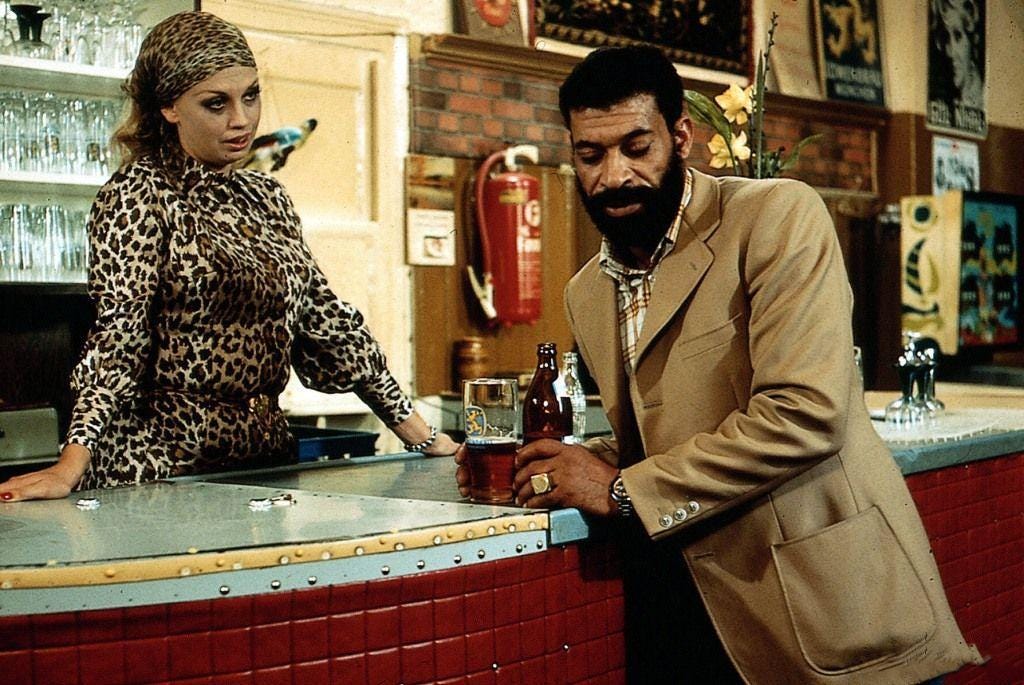

When Emmi and Ali marry and move in together Emmi is isolated by her colleagues and neighbours. The local grocer won't serve Ali because, he claims, he doesn't speak German. The neighbours call the police when Ali plays cards with some friends. Someone says, 'Four Arabs in her apartment. You know what they're like. Bombs and all that.’ At their wedding lunch the couple are alone while being stared at by strangers, eating in the Munich restaurant Hitler used to frequent.

At this point Fassbinder moves the story on. When Ali and Emmi return from their honeymoon attitudes moderate. Her children can use Emmi as their babysitter; the grocer welcomes Ali: he has been made aware of their mutual dependence now he is afraid of losing customers to the expanding supermarkets. ‘In business,’ he says, ‘you have to hide your aversions.’ Emmi's colleagues take up with her again when they find another victim to bully, this time a Yugoslav woman. Not only that, her female friends begin to find Ali attractive, even feeling his muscles.

Towards the end of the film, after a confused and persecuted Ali sleeps with a girl from the bar, Emmi goes to some trouble to win him back, insisting their love is more important than any minor transgression. Then, when Ali falls ill with a perforated stomach ulcer, she takes him to hospital where he is left in the care of a doctor - Fassbinder's father was a doctor - who informs her that Ali will have to return because his ulcer won't get better. The doctor has seen this before with other immigrants: their lives are so difficult they fall ill repeatedly.

The notion of integration is one that is discussed constantly in Europe today, and the character of Ali perfectly illustrates the difficulties and double-binds it involves. The language used against him is the familiar vocabulary of the racist, whether the victim is a Jew, Negro or Muslim, and it involves the most important things: money, sexuality, disease and social status. Considering their envy of this Arab man is, at least, a way for those around him to be reminded of what matters most to them - if only in inverted fantasy.

The immigrant should work but not belong; he mustn't forget his place as an outsider. If he 'integrates' too much he is accused of taking over, or of fracturing the organic unity of the existing society. If he keeps his distance he is living in a ghetto, thus creating social disintegration. In the end he is indigestible, and Ali represents in his sick body the contradictions of the society he now inhabits.

There are no Black Shirts, political parties, marches, or any mention of the holocaust in Fear Eats the Soul. The hatred is deliberately low-level; it is simple everyday bourgeois racism. Fassbinder is showing us that fascism starts at the bottom, rather than being imposed from above. It is not the authorities who harass Ali, it is his neighbours. And although Fassbinder is too pure an artist to become didactic, he is reminding us that Europe has been through this before and that this is how it might start again.

The society which Ali has moved into is shown by Fassbinder to be stagnant, if not decadent. Emmi's children are cruel towards her, indolent and envious, and without motivation or desire. Seemingly traumatised by the past, they are numb and uninterested in their mother's passion for Ali. Their souls have been devoured by hatred, and Fassbinder cannot find much about their way of life which is valuable or alive. Ali as the alien, scapegoat or awful Thing - he is both a question and a provocation - appears to occupy an empty place, a position that almost any outsider could be put in. Jews were often referred to as the Negroes of Europe.) Ali is not hated because he is in reality dirty, over-sexualised and ambitious etc. He is considered to have these qualities because he is an immigrant. That is what the immigrant has been made into.

Perhaps if the host community can focus their hate on Ali, he at least absolves those around him from hating one another. His presence seems to create some kind of unity. This is not unlike the son Gregor Samsa in Kafka's great story Metamorphosis. The gain of Gregor becoming an insect is that his horrible transformation creates accord and, eventually, happiness and freedom in the family. The last line of Metamorphosis runs, 'And it was like a confirmation of their new dreams and excellent intentions that at the end of their journey their daughter sprang to her feet and stretched her young body?

But Ali also reminds those around him that although they don't want anything to change, they might require a catalyst. In this regard Ali represents the future; there will be more like him, and deeper difficulties. How will these Others be absorbed, and how will everyone have to change in order to make a productive life possible? What sort of society can be made from these elements?

In 1989, fifteen years after Fear Eats the Soul, when the Berlin Wall came down and communism collapsed in Eastern Europe, a fatwah was placed on the life of Salman Rushdie.

There is no Muslim community in Fear Eats the Soul, only a group of Moroccan buddies in inhospitable territory. But by 1989 in Britain the Muslim community was becoming a force; they were no longer innocent like Ali, but active and persecutory themselves.

Quickly they were able to pass around information about The Satanic Verses, organise for the book to be burned in Bolton and Bradford, and put pressure on both the publishers Penguin and the British government to have it banned.

There's no reason to think the Muslim community would be any more cohesive than any other. However, there was one issue which briefly brought these believers together. It wasn't inequality, discrimination or hatred which created this organisation, but an insult. And it wasn't the host community they were attacking, but another Muslim, a highly regarded writer. The community was a community because of its underlying religion. Being an immigrant wasn't an identity, or enough of one, except for others. The 'deviant' Rushdie created a brief unity.

The Satanic Verses begins with a terrorist attack on an aeroplane, and this explosion presages the explosion of identities Rushdie explores in the book. As Rushdie himself put it, 'How does newness come into the world? How is it born? Of what fusions, translations, conjoinings is it made?'

The super-acceleration of the world in the 8os; migration and metamorphosis: if you can't go home again because both you and home have already changed, you can at least remake yourself in the new place although it rejects you. But you'll be different to your parents, and most likely far from what they wanted you to be. You might feel you have betrayed them, but that the way to return is via religion.

Amongst other things, The Satanic Verses is a celebration of fragmentation, hybridity and breakdown, psychosis by another name. This is a painful mad state which might require the reintroduction of limits. The authorities are called in when there is too much enjoyment; they re-establish order and renunciation over the vortex of obscene enjoyment. One cure they might offer could be the safety of certainty, knowledge of the absolute truth; the certainty of the very religion Rushdie, as an artist, can't help being sceptical about.

If novelists and the religious are envious and fascinated by one another it is because religions and literature approach the same subject, knowledge of the world and how to live in it as sexual and dying beings. Like literature, religions are a form of myth, a creative function of the human imagination; Mohammed, Jesus and the Virgin Mary can resemble characters in a drama, and we can argue about their virtues and failings as we would with anyone else.

Religions are, among other things, a form of explanation, of story telling and order making. As with literature, these stories are, then, useful delusions. But where religions seek to eradicate conflicts, installing some notion of ultimate harmony, literature sustains conflicts as arguments worth having. The Satanic Verses is concerned with the necessity of doubt in this process, returning religious myths and narratives to man as objects of creativity and of enquiry. All texts, like all lives, are endlessly open to interpretation, satire, slander, idealisation. Religions, like the novel, are mankind's dream and a high form of useful play. God is man's greatest creation, as well as his worst. Man is more creative than God.

But if forms of worship are man-made, they can be modified by man; they can be reinvented, according to need. But where literature is critical - Baal in The Satanic Verses states, ‘a poet's work is to name the unnamable, to point out frauds, take sides, start arguments’ - religions, called 'sacred', require obedience and often silence: If religion is man at his most creative, it is also him at his most authoritarian. Not that you can underestimate the pleasures of obedience.

Nietzsche writes, ‘What we do in dreams we also do when we are awake; we invent and fabricate the person with whom we associate - and immediately forget we have done so.’ As Fassbinder points out, we fictionalise the immigrant, turning him into the monster of our imagining. At times he is an oppressed or greedy immigrant, and at another a revolutionary fascist, a proto-bomber hating the West, wanting to change it into his own idealised image.

We can frighten ourselves, taking these stories literally. But myths are imperative: nothing is still, migration and metamorphosis are our destiny, a passage to death. We live in fantasy, hallucination and imagination. The self cannot be mastered or contained; parts of it are always liable to sheer off and fly about, looking for a character to inhabit.

You can find the published works of Hanif Kureishi here on Faber Books (available for delivery in the UK).

Thanks for this brilliant commentary, Hanif. In 1976, my young filmmaker-fiance, David Hancock, was given a Ford Foundation grant to follow a young Algerian making his way to Europe to find work and start a new life. Sadly, David died of cancer that year and the film was never made. But I know he would have explored all that you say here. Thanks so much. My heart goes out to you. I've loved all your work and these dispatches are evermore poignant and necessary for all to read. Gretel Ehrlich

This essay is hallmark Hanif. Sensitive, alert and tender, but unflinching and full of balanced clarity, relating the human heart to society and how the dark impulse of intolerance and persecution cuts through us all, and in a social sense, within minorities as well as majorities, communities and societies, and families too.

Remember, Hanif aroused some intolerance because of My Beautiful Launderette, and its beautiful and brilliant and fearless eye upon British Asian culture and gay culture in nascent multicultural England.