Dear Readers,

The Kureishi Chronicles will be a year old next month. Time certainly hasn’t flown, but this blog has kept me alive. Thank you for your loyalty and continued support.

I ask that if you enjoy The Kureishi Chronicles, believe in paying for good writing, and want to help with my recovery, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

What's the nature of your working relationship with your book (s) editor (s)?

HANIF

Currently I am working on a year’s worth of dispatches which, with my son Carlo, and the Hamish Hamilton editor Simon Prosser, I am converting into a book which will be called Shattered, an account of my injury and the year that followed it in five hospitals. It’s proving to be a lot of fun to work on, since Simon is an experienced and committed editor, and was the reason I left my former publisher Faber & Faber and moved publishing houses. Since my injury I have needed an editor who is far more involved in my work than previous editors were. I get tired easily and unfortunately cannot do any typing myself, and so although, much to my surprise, I’ve completed a book during the worst year possible, I am unable to finish it on my own. Simon is a pleasure to work with, since he is smart, undramatic and sensitive; he doesn’t force changes on you, but when he does require alterations, he always gives a full justification. With every line or mark there is an improvement. We are going through the entire text with a pen, discussing cuts and how pieces can be moved about to improve the pace and direction of the story. He suggests where new material can be added, characters embellished, and expansions made.

I have had some harsh run-ins with editors over the years, particularly at the beginning when I was wrangled into making changes that I didn’t believe in. I guess I wanted to please the editor or, my likely, didn’t want any conflict with them. I gave way too easily. I regret it, but I had far less of an appetite for disagreement than I do now. I also believed that others who were older and more experienced than me knew better, particularly when it came to prestigious magazines like The New Yorker and Granta.

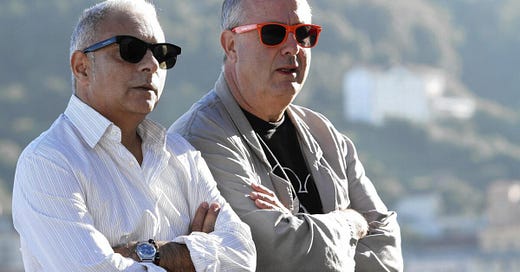

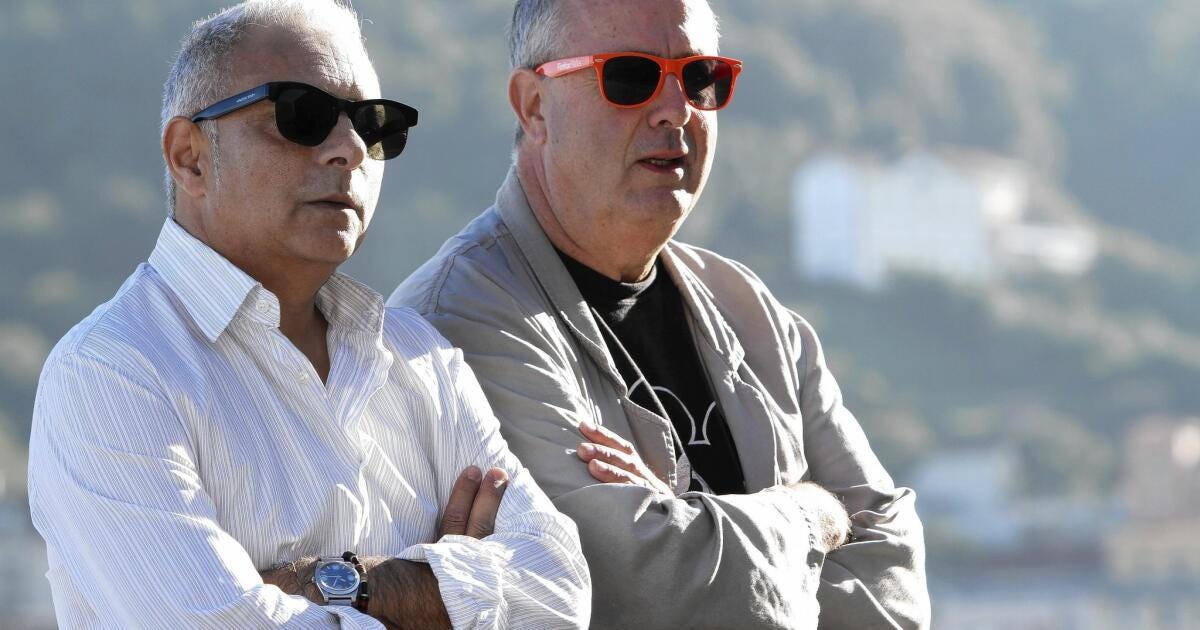

Over the years I had some hair-raising clashes with my late pal the film director Roger Michell. Mostly we enjoyed working together; we had a lot of fun and liked one another’s company, shared many jokes, and accomplished things together we couldn’t have done alone. But towards the end of our relationship, around the time we did our movie Le Weekend, things got quite rough. At times, Roger could turn angry if not nasty. He could be a bully, and I could be passive aggressive. He would delete parts of my screenplay without permission and add his own material, though some of it was excellent. At one point he even asked for a writing credit, I said “Fuck off, count yourself lucky if you get a directing credit.” In all these relationships, you must learn when to resist and when to give way - if you relent, you may regret it,

A couple of years ago, a long story I wrote for Francis Ford Coppola’s literary magazine, Zoetrope, was harshly edited and twisted, which I found abusive. I am still smarting from it.

I’m an editor who would love to have a go at writing. But always at my back sits my inner editor. I can’t make him go away. Do you have a suggestion for me?

HANIF

It is difficult to rid yourself of the devil on your back who insists on discouraging you. I say it is difficult but not impossible and with enough resistance you can shut him up so that you can get on with your work.

Do you believe one runs out of things to write?

HANIF

Some writers, particularly genre writers like Agatha Christie, P.G. Wodehouse and George Simenon never run out of things to say. They can recycle themes and characters throughout their lives. Other writers, who insist on saying something new each time can indeed run out of novel things to say, since they have reached the limit of their imagination. And so what? It would be a good opportunity to find something new to do with your life. It is not necessary to write all the time, it might be a good idea to try something else, there is nothing wrong with that.

How does one escape the chains of one’s own suffering enough to occupy fictional characters? Or are we doomed to write non-fiction forevermore?

HANIF

One of the things you might do with suffering is to take the time to convert it into stories for others. This may shrink your suffering by entering it into the symbolic field.

How do you keep your pace all year round? To keep writing and posting and at great quality and quantity as well?

HANIF

With the help initially of Isabella, and now with my son Carlo, I can produce a quantity of work that I wouldn’t have been able to do previously. Because I can only dictate, the often slow and frustrating work of actually writing, editing, and moving things about on the page is done by someone else, allowing me to just think and speak. When I get tired, my spirits are lifted by collaboration, and I can do more than I did even before my injury.

Any tips on writing dialogue, especially for the screen?

HANIF

It is well known that the dialogue in films and TV shows has to progress the narrative; it also has to match the nature of the characters, it has to sound like them. David Chase, the creator of The Sopranos, said that his characters do not always say what they feel, concealing their intentions, so that the audience has to work to understand exactly what is going on. This is subtle writing. There has to be variety, scenes can’t all be the same length or pace, but what is true of all drama is that characters are constantly trying to extract things from others; love, information, recognition, and so on.

Hanif, you are a living legend. Please continue. You inspire and energise always.

Thank you.

Loved the unexpected answer you gave to Sonia Pilcer: not “there’s always more to write about” but maybe, for some, there isn’t. Also your last line, about characters always trying to extract something from others in their dialogue. A good reminder!