All first novels are letters to one's parents, telling them how it was for you, an account of things they didn't understand or didn't want to hear, saying what couldn't be said, providing them with a bigger picture.

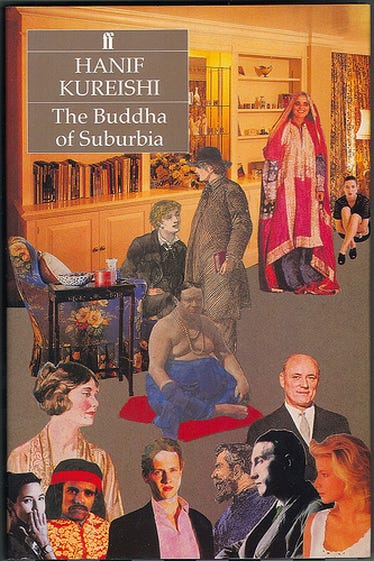

It was the late 80s, and I was in my early 30s, when I began to work on The Buddha of Suburbia. The two films I'd written previously, My Beautiful Laundrette and Sammy and Rosie Get Laid, had bought me time and money. The success of My Beautiful Laundrette had given me confidence that the writing tone I'd found, could be extended into the novel I’d wanted to write as a teenager.

I had been no good at school, but always felt more alive than the people around me. I was a horny bookworm, and novels got through to me. I thought I'd do one. I did several.

They were not published. But I did write what became the first chapter of The Buddha of Suburbia, as a short story for the London Review of Books, published in 1987.

I believed that was that. Then I kept thinking there was more material. I had an intense experience which can happen to writers, when you understand that your subject is right there; you have lived it already, and that world is waiting to be converted into scenes. If people were not writing books about people like me, I'd write one myself, spitting out all the painful things, rudely, lightly. Someone said to me, write your pleasure. I did.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to THE KUREISHI CHRONICLES to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.