Dear Readers,

The Kureishi Chronicles will be a year old next month. Time certainly hasn’t flown, but this blog has kept me alive. Thank you for your loyalty and continued support.

I ask that if you enjoy The Kureishi Chronicles, believe in paying for good writing, and want to help with my recovery, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Below, an essay about accidentally appearing in a documentary about the band Nirvana, and some answers to your questions.

Hanif

Sachin has been away for a couple of weeks, and when he comes bouncing into the house, he seems to have grown. As a family we were never huge; Tracey and I are about the same size, five foot six. Sachin is wearing thick shoes, but he also seems to have got wider. As he is a twin, I can compare him to his brother, and he does seem to have got broader as well as taller.

It is a sunny winter’s day, and we go out of the house and onto the Shepherd’s Bush Road, me in my motorised wheelchair. As we pass Le Citron, a French Restaurant - formerly the notorious Café Rouge, where I was seen every night, carousing with friends - we are both struck by the same memory. About a year ago, Tracey and Carlo were watching a documentary about the band Nirvana and their first London tour. The band had the good fortune to be staying in a rough B&B on the Shepherd’s Bush Road, and were filmed larking about outside the Rouge. The producer of the documentary had now returned to the scene, filming the Shepherd’s Bush Road as it is today. By coincidence, they filmed Sachin barrelling into an establishing shot, and me crouching in the doorway of the Le Citron, ready to jump out at him. Because I am omnipresent in the area, Tracey and Carlo had in fact half expected to see me – and so they did, and they cried with laughter.

It is difficult not to think of this as Sachin and I make our way up the road, but after a few yards, I am more concerned with the unevenness of the pavement. If you are newly in a wheelchair, you will be aware, for the first time in your life, of the exact nature of the pavement you are covering. You are closer to the ground than ever before, every bump shoots through you with a shock.

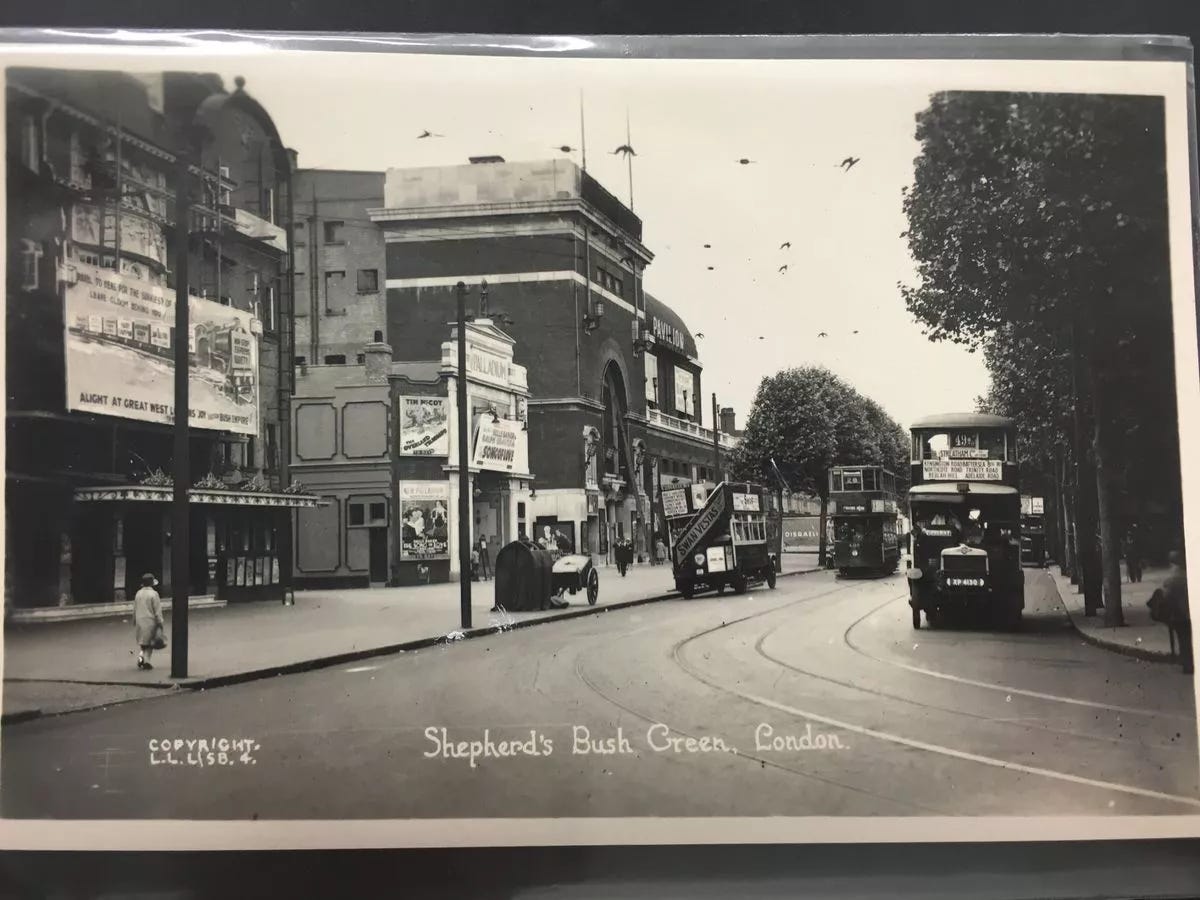

Things improve when we get to Shepherd’s Bush Green, where the ground is smoother. Soon we are outside my barbers where a rough looking man in wheelchair skids up close to me and starts admiring my chair, pointing out its features enviously, and asking where I got it. I explain that it is the NHS’s finest.

It has been more than a year since I have had a haircut from my constant barber, the Macedonian Lula, who I consider to have the hands of Michelangelo. Our family have known him for fifteen years, since he was installed in a leaky shed next to a petrol station on the Goldhawk Road. Lula, in fact, gave Kier his first adult haircut, and the boys and I used to get shaved there. Now, Lula has two salons and a restaurant nearby, as well as a permanently worried look on his face.

Sachin gets me over the threshold and into the shop where a space is made for my chair. Kier, my youngest son, joins us. It is a relief to be back doing normal things, on a regular day, in my hood. Often all of four of us would be in the barbers together; gossiping, listening to music, arguing over who goes first, and trying to avoid one of Lula’s fresh recruits who would inevitably give you the ‘Serbian Rapist Look’.

During Covid, when you weren’t allowed to fraternise, the boys and I would have to get haircuts surreptitiously. We would meet around the back of Lula’s building, passing through an anonymous door, along several damp corridors, and into a room we’d never been before, with no windows. Sat before a miniscule mirror the size of an iphone screen, illuminated by a single bulb, Lula would get to work with his scissors. It was as if we were part of an underground resistance movement, or doing a drug deal.

Now, looking out of the window, across the Green, I see someone I recognise. It is the father of one of Kier’s friends. When Kier was at primary school, he came home one day after playing with this man’s son, and announced that he had become a Muslim. I found him on his knees praying in front of the television, and he asked us, his parents, to respect his conversion. The practise of this new religion went on for a few days. I was absolutely furious and wanted to go round to this man’s house and give him a bollocking. Luckily, Kier soon gave up his religious practises and continued to watch TV and eat sweets in his spare time, as he had done formerly. Now I ask him why he converted, and he tells me he wanted to be like the other kids in his class. He didn’t want to feel left out. I tell him there’s nothing bad about feeling left out; in fact it could be a luxury, a pleasure, and a form of self-determination that would one might relish.

Sachin, Kier and I, in the sunshine, cross the Green and back onto the Shepherd’s Bush Road. It has been a lovely day.

To the extent that you can discern, what aspects of your writing practice were *improved*, or pleasingly changed in some way, by the dictation and editing methods you've had to develop post-accident?

HANIF

Since my accident I have had to develop a new method of writing, directly dictating to a member of my family, usually Carlo. Since he is sitting here, fingers poised over the computer, there is pressure on me to produce work straight away. I can’t piss about waiting for inspiration, so I have to open my mouth and start talking, more or less without thinking. As it has turned out, and much to my surprise, it is a method which is working well for me. I never knew that it would, but it encourages you as a writer to get on with it, and not worry too much, at least initially, about the quality. The point is to produce a serviceable first draft, which can later be revised into better sense. It is the way I like to work now, I wouldn’t’ like to go back to the old, sitting-at-your-desk method, which is just too slow.

Carlo and I separate writing and editing over two days. On the first day, we bang out a rough draft, and on the second day we go through it, word by word, making it presentable.

I suppose a more general way to phrase the question is: how much empathy for the general reader should the writer have re: the readability and approachability of their work?

HANIF

I wrote about this in an earlier blog, which I’ll copy below.

It is important when you are writing, or indeed creating anything, to be aware of an audience. This may be one person, several, or a crowd. But this will help to orientate you as a writer, so that when you are reading through something you have written you will ask yourself, will the audience be bored by this, are they still with us, or have they left already?

So, for instance, the writer should be aware that a novel should get off to a good strong start, that there should not be pages of warm-up, of easing slowly into the story. It is best that it should start dramatically. This will help the reader to become interested in the story.

If possible the story should have a certain pace, which will keep the reader at the book. As a writer, you must be able to separate yourself into both author and reader. I know this sounds daft, but it is possible. I am neither an arts-for-arts sake guy, nor am I a guy who likes art to be purely commercial; the best artists, the ones I admire – Miles Davis, The Beatles, Hitchcock, etc – are the ones able to combine serious ideas within a commercial envelope.

I heard you have been working with Emma Rice to turn The Buddha of Suburbia into a stage show for the RSC. I would love you do a blog post about how you and Emma work together, what are the processes involved in turning a novel into a play?

HANIF

I like Emma Rice very much, and I have enjoyed working with her on The Buddha of Suburbia as a stage play.

Infuriately I had this accident, which has prevented me for being as involved in the production as I would like to be. I attended a workshop at The National in 2022, but since then I have been in hospital. Though I do meet with Emma from time to time to discuss ideas for the project.

Utterly brilliant to read this, thank you. I agree that the “Serbian rapist” haircut is one to be avoided. I used to live next door to someone whose hairdresser had apparently been inspired by the Bayeux Tapestry. Also not a good look, especially on a woman.

Thanks so very much for responding to my query on your new writing practice. It’s an inspiration, like nearly everything in this blog.