Dear Readers, a small note before we begin. Since my accident in December which left me without the use of my hands or legs - a considerable inconvenience - I have been writing, via dictation, a weekly dispatch, which you all read and respond to with such love and thoughtfulness. You have kept me a live. As we approach six months, I kindly ask that if you have the means, it would mean a great deal if could support my writing by becoming a paid subscriber, and keep this show on the road.

My Loving Readers and Scribblers,

What a privilege it has been to read yet more of your wonderful and elegiac writing. I am so humbled by the care taken with each one, how personal they felt, and the fortitude and strength of spirit they exemplified. These are stories about tragedy and resilience; how our lives can be altered irrevocably in a cruel moment, and the loved ones who remain unwaveringly steadfast in their devotion to us, absorbing our pain and demanding that we carry on.

It was almost impossible to choose the winners, for all of them were so beautifully written and intimate. I must urge you all to continue writing, whatever the outcome.

The stories below were chosen for their sagacity and control, sincerity and perceptiveness, within the small frame of time prescribed.

I hope you enjoy them as much as I did,

your loving writer,

Hanif xx

Life Hurts

Sepulveda is the longest street in Los Angeles County, as well as my mother’s maiden name. From her, I inherited bad teeth, a bad temper and an interest in the paranormal.

My father — Scots-Irish and a Methodist preacher’s kid from Appalachia — wasn’t averse to the supernatural either. After a World War II tour of duty in North Africa, he lugged home an authentic mojo. It’s a mahogany-red, heart-shaped, leather-bound amulet, stitched with white reeds and topped by a tassel of leather fringe. It supposedly contains a monkey heart, but that might just’ve been my dad’s tip of the hat to a Swahili fairy tale.

Of uncertain age, it bears the patina of countless incantations by who-knows-who for purposes unknown. When Muddy Waters sang, “I got my mojo working, but it just don’t work on you,” he was talking talisman. Friends injured by nasty divorces, child custody battles and bad neighbors often ask if my mojo's Hoodoo can solve their issues by getting rid of the problems.

I’ve never been asked to rub that mojo for pure purposes. There is enough Irish superstition and my father’s kindness in me to know what you put out is what you get back. I can imagine my dad tucking the charm into his flight jacket before bombing the hell out of combatants in Europe, the Mediterranean, Africa and the Pacific islands. Knowing him, he hoped to protect innocents below from becoming collateral damage.

My mother, on the other hand, had no compunctions. She was all about retribution. Lore has it her family roots reach back to Island Carib, the fierce cannibal tribe of the Caribbean. Having seen that side of her, I believe it. Floating in and out of hospice care on seven occasions, she went down fighting at age 90 from a dementia that slowly ate her brain over the course of 15 years.

Long divorced from my mom (of whom he never said a bad word, despite her running off with a Colombian bombero, blowing her settlement and moving to Bogota), my dad’s end at age 64 was also heroic. He suffered an aortic aneurysm and lay on his bathroom floor for two days before being found. He got to the hospital too late for survival but held off dying for 48 hours until I caught a flight from the West Coast. He died 15 minutes after my arrival. “He was waiting for you,” the nurse whispered in my ear as I leaned over his bedside.

My parents were warriors, especially in death. That got me wondering whether elephants really travel to a tribal bone yard to bury what’s left of their life. Most cultures contain chapters on senicide, a concept I encountered as a child reading Jack London’s story, “The Law of Life.” There are worse things than being left to die in the forest or on an ice floe.

From my perspective, it’s never too early to think about where you’d like to die from the thousand tiny and large cuts that constitute life.

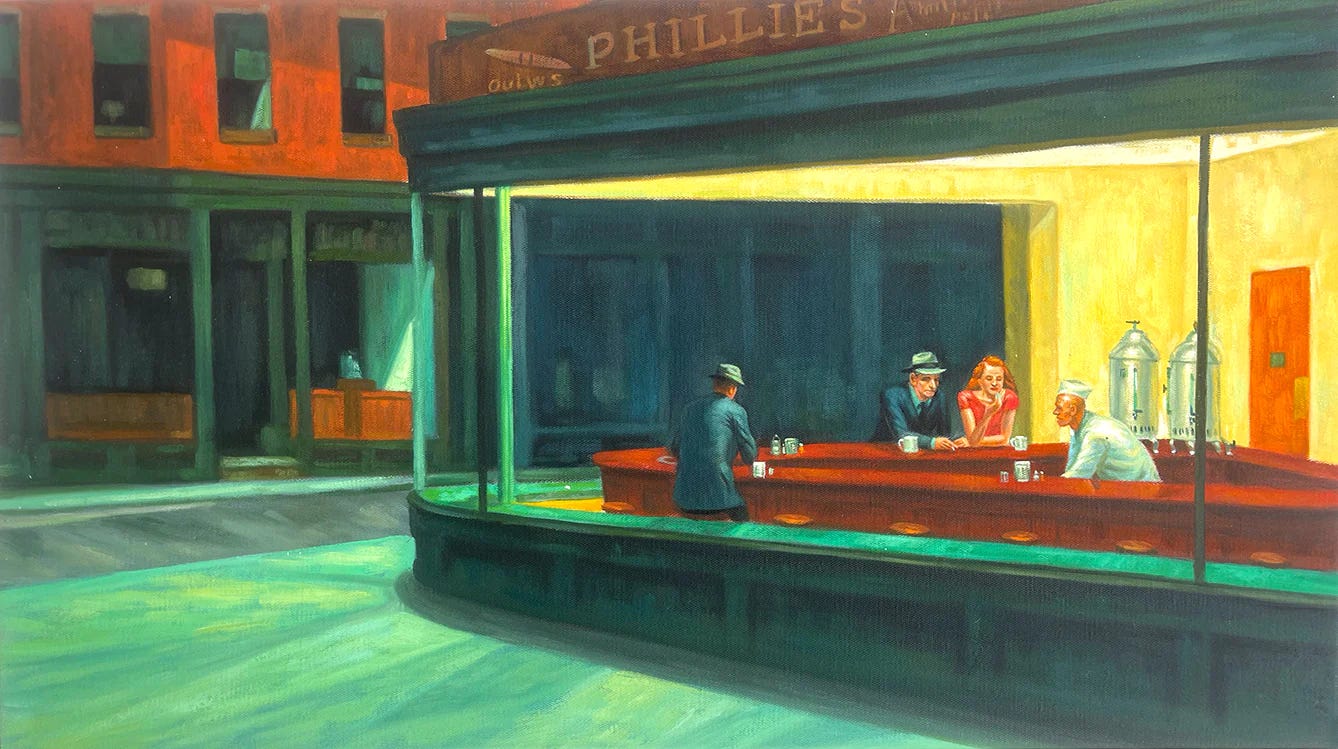

As a music writer, a big part of my job was searching for the entertainment gold standard in the coal mines of nightclubs. This butt has embraced more Naugahyde in more dive bars than I can count. When the heartache and thousand shocks that flesh is heir to finally catch up to me, I hope to find myself at the Sans Souci. A longtime press corps and ne'er-do- well hideout, Sans Souci— French for “without care” —harkens to the caveman era of highballs and unfiltered cigarettes. Legend has it that the bar opened in the 1930s to launder heist money for the Lavender Hill Mob of Los Angeles.

Sans Souci attracts all kinds, from the homeless to celebrities performing at the theater across the street. For old school patrons it's a huddle around the horseshoe bar sounding off on opinions others listen to, even if they ferociously disagree. An advertisement for the band exalts, “The Sewer Is my church!” Its dimly lit confines and jukebox are an antidote for the loneliness that ails us; for those not busy being born, who are busy dying.

For the bartender Sans Souci is selection 45-01, Wilson Pickett's "Mustang Sally."

For the gentleman nursing a schnapps it's 18-02, Brooks & Dunn's "A Man This Lonely."

Me? I’d be happy to end my life listening to 00-01 Nat "King" Cole's "Unforgettable."

Luckily, I have a mojo. Maybe it works for me.

A Few Years Ago

By Carol

A few years ago, I received a book in the mail from my best friend. It was entitled Recovering From Trauma - Stories from Victims. Cathee was really excited because her story had been included in one of the chapters. Indeed her story was pretty compelling. In August of 1967 her family drove from Kenosha, Wisconsin to the central plains of Kansas.

Her mom had grown up on a small farm outside of Beloit, Kansas and it was a tradition for the family to come together and help with harvest. After a long 12-hour drive with 3 girls and a dog in the back of the Rambler they arrived on the farm Saturday evening. Her uncle was eager to show them the wheat fields and the new combine. Traditionally they would take one cut around the perimeter of the field to see if it was dry enough to harvest the next day.

It was also a tradition to let the kids ride in the back of the bin. It was considered a privilege to sit upon the pile of cut grain and feel the flow of wheat pour into the back. Cathee and her little sister were lifted and placed in the bin. Her dad hung onto the ladder by the front seat and talked to their uncle as they made the lap around the field. Her uncle steered the combine over to the silo to unload the wheat. But lost in conversation, he forgot about his two nieces in the wheat bin and he flipped the auger switch on. Cathee was tall enough to grab onto the edge of the bin and she hung on with all her strength as she watched her six year old sister helplessly circle around with the wheat as it was sucked down towards the auger at the bottom of the bin.

Her dad immediately screamed at her uncle to turn the auger off but it was too late – her sister’s foot was already sliced to ribbons. Her dad reached down and grabbed her sister as her uncle whipped off his shirt to stop the blood flow. They ran to the car but in the rush to save her sister, my friend was left hanging onto the wheat bin, terrified she might be sucked down next. She felt overwhelmed, frightened and alone. She states this trauma affected her for the rest of her life. And it was very cathartic for her to see her story published and her trauma validated.

But my reaction after reading her story was one of anger. Because you see my best friend is my sister and I was the little girl whose foot was cut off. I felt that if anyone was traumatized it was me not her. I was the one with a lifetime of strapping on my prosthesis every morning to make it to the bathroom. I was the one with endless appointments to doctors to manage my pain or replace the leg after it had broken. Surely my trauma was bigger, longer lasting and more painful than hers. Why would she still be holding on to that moment, that in comparison to my experience, wasn’t that big of a deal?

But in truth - I was the one who was pulled out of that bin and was supported from that day forward. My father hoisted me onto his shoulders whenever I was tired of walking. My mom took me to endless doctor and prosthetist appointments. My family encouraged me through swimming lessons and gymnastics. I married a big strong man and backpacked around the world with him. He carried the heavier load and kept me safe. I had friends and a wonderful profession in health care and a supportive family surrounding me my whole life. I cannot claim to be traumatized.

And yet I never took the time to understand that Cathee did. She still felt abandoned and forgotten. She has spent her adult life trying to understand the deeper mysteries of life. She channels spirits, she wanders off into the mountains, and luckily she’s found a good man with whom to share her itinerant life. But she always chooses solitude over friendships. And in her quietness she had been struggling with a trauma I had not recognized or even discussed.

I guess being a part of a traumatic experience isn’t the issue. What’s more important is what happens afterwards – the feeling of being pulled to safety.

Cathee chose to disappear 2 years ago and only recently reached out to us. I hope it’s not too late to pull her home.

Surviving a Life Interrupted

by Jenny Tatsak

It’s 8:51 on Tuesday morning and I am laser focused on the clock on my hospital room’s wall.

Only a month ago, by this time in the morning I would have already packed my daughter’s lunch, dropped her at school, reminded my husband for the umpteenth time to get the trash cans to the curb for garbage day, and reveled in some alone time during my bumper-to-bumper commute to the college where I work as a professor.

But not today and every day since I woke from a two-week coma, the parting gift from what should have been a routine surgery to repair a nine-year old hernia acquired during childbirth, that left me with an internal flesh-eating bacterium that ravaged my insides. Given only a 10 percent chance of survival, I beat the odds, but was left paralyzed below the neck.

So now the highlight of my day is when the surgeons peak beneath the gauze disguising the massive hole in my abdomen; the site of the original infection and where the remaining infection is being sucked out by two wound vacuums attached to me at all times.

The remainder of my time is spent fixated on the clock’s second hand, with its audible and rhythmic “tick” until the minute hand advances putting me one minute closer to my next ration of ice chips. Like many reliant on ventilators, I developed a swallowing dysfunction making pneumonia likely, which for me would be a death sentence. No food and no tall drinks of water - only six ice chips each hour.

What remains, as a new constant in my life interrupted, is a kaleidoscope of emotions – fragmented and blurred together as well as intense and fleeting -- ranging from gratitude to be breathing to the more pronounced and vivid grief for the life I had once enjoyed and deep despair for the limitations of my current existence. My only solace is six measly ice chips.

I deserve a drink of water, basic hydration, for all that I have and must still endure. If only to alleviate the pain of my severely damaged vocal cords from the ventilator, which makes every labored syllable sound and feel like I choked on a mouth full of gravel. Even moving from my bed to the chair, so close I can touch it with an outstretched hand now requires one of those parachutes with handgrips toddlers use to propel balls into the air except my body is what is suspended in midair. Affixed to steel pulleys on tracks in the ceiling, the sturdy canvas folds me into a stork-like package used to deliver me to my destination.

And then there is physical therapy and my physical therapist, “Frau Blucher,” as I refer to her because she has the same thick German accent and invokes fear like the iconic character from the cult classic Young Frankenstein. Her therapies are equal parts torture and invention as evidenced by the hard stainless-steel table she binds me to with thick leather belt-like straps to simulate standing - a cross between an industrial kitchen’s work surface and the electric chair. I imagine I look like the scene in Silence of the Lambs where Hannibal Lecture, restrained in a similar manner, meets Clarice. Frau Blucher, I am sure is a disciple of Hannibal Lecter given her affection for agony.

All these dreams, emotions, new and unwanted experiences taken together make me ache for a life beyond these same four cinderblock walls. I cling to the hope so desperately that my recovery, albeit long and difficult, will culminate in some triumphant return to my definition of normal. Like the payoff of a movie montage where the hero defies all odds. That my life interrupted can someday be condensed into some inspiring tale to regale strangers with in casual conversation.

Patience has never been my strong suit; I want my ice chips now just as I want my old life back now. The ice chips signify a promise of what could be. A future moving freely, talking painlessly and gesticulating wildly. But the wait is unbearable. What is left is the fear I will be bed-ridden and unable to care for myself or anyone else, leaving me utterly hopeless with only an empty glass. But once every hour, if only for a few minutes, I can suck on an ice chip, sooth my throat, refresh my spirit, and remember my old life with a glimmer of hope for what could be.

Hanif, I am so honored by your selection. I also wanted to let you know that Susie's "May" was added to the bottom of my "Surviving a Life Interrupted." Her piece begins with "It's exactly as you see it on TV." Should you be able to revise the post to separate the pieces to ensure Susie is credited, it would be greatly appreciated. Again, thank you for the recognition and for the Kureishi Chronicles.

Dear Hanif - I’m honored my story was chosen as I was moved by all of the stories that were shared.

As a post script - my sister Cathee finally made her way home. She spent 2 years wandering in the deserts of New Mexico - but that story is for a longer essay. I am just happy my middle sis is back.

Am hoping you too will be home soon.