SMALL TOWN REBELS

Pop was a paradise for no-hopers, bums, outsiders, fairies and failures.

Dear Readers,

I present to you my final piece on music.

This is the last weekend to take advantage of the flash sale.

Yearly subscriptions are priced at just £35.00.

That’s less than three pounds a month for all my writing.

So, if believe in paying for good writing and want to help with my recovery, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber.

In addition, if you wish to preorder my forthcoming memoir, Shattered, you can do so by following the links provided here:

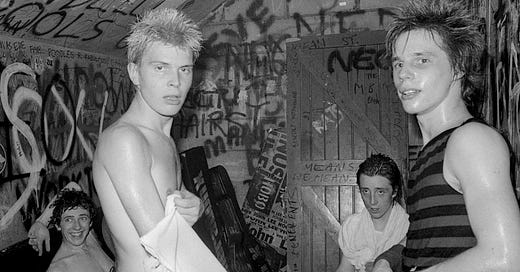

I was on the train to the coast with Bill Broad, Steve Bailey and another school friend, when Bill, now known as Billy Idol, slipped a tab of acid onto my tongue. Then he stood up, wound down the window, and ordered me to throw my watch out. This watch, which my mother had obtained with Green Shield stamps, had been my sixteenth birthday gift. Billy said, “Do it now! Time doesn’t matter.” I complied.

I learned later that this discarding of the watch was something Bill had picked up from the movie Easy Rider, an incident which would later turn up in TheBuddha of Suburbia, when Charlie Hero invites his school friend Karim Amir into his bedroom for a joint, a telling off, and a wank.

We four school friends arrived at the coast as it was getting dark. By now, we were tripping off our heads. Pitching our tent on what we thought was a rugged patch on a coastal path, we woke in the morning with two policemen poking their heads into the tent. It turned out that we were not in fact by the sea, but in a children’s playground, next to a swing, in Bournemouth.

The policemen rang our parents to confirm that we were not runaways. Bill Broad, who later formed Generation X, and Steve, who, as Steve Severin, became the bassist for Siouxsie and the Banshees, were two among many musicians who emerged from the suburbs at the beginning of the seventies.

Yesterday, I did my first onstage interview since my accident. I was sick with nerves in the afternoon, terrified that my catheter might get blocked and I would pee myself on stage. I even threw up in my favourite café on the Goldhawk Road. I was worried about my appearance and how I would be viewed as a disabled person.

Despite my fears, I enjoyed the talk. The audience was sympathetic and responsive. A young woman asked me about the optimism of my first novel. Oddly enough, that morning, Carlo and I had been discussing optimism as a generational force, wondering where it came from, and how culture worked to inspire and bring about innovation.

I replied to the woman that despite the gloom and boredom of the suburbs, there was a lot of resourcefulness, particularly in regard to music and the arts that emerged from it: photography, fashion, journalism and film. Pop was a paradise for no-hopers, bums, outsiders, fairies and failures. Listening to The Velvet Underground – tough, awkward, avant-garde music – made us want to become artists. Our style was informed by A Clockwork Orange, Cabaret, and Visconti’s outrageous masterpiece, The Damned.

When I was fifteen I formed a band called The Orange Socks, but since I couldn’t sing or play, we didn’t get very far. At one all-night party, I was strumming a guitar with some local musicians – including Billy Jenkins, who would become a great jazz guitarist – and I remember Bill Broad (Idol) looking at me with some contempt as I attempted a blues solo. What options were left for me? To become a roadie?

Musicians like The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Joni Mitchell, Crosby Stills and Nash, Marvin Gaye and Jimi Hendrix were leading the culture, and were far more important than the latest novel by Iris Murdoch. Music had taken over. I wanted to be part of this scene, but I also wanted to write fiction. How could the two be put together?

It took me a long time to work out how to integrate pop and popstar aspiration into my writing. I hadn’t seen it yet in contemporary fiction. The character of Charlie Hero was an amalgam of the young, talented, pretty boys I had grown up with.

Writing is a form of integration, it is where a young artist will, if he or she is lucky, synthesise their various preoccupations; where at last everything they have been conscious and unconscious of – what they have been thinking about – will come together in a coherent pattern or story. This is why it might take so long for a person to become the artist they need to be. It could take ten years.

It certainly did for David Bowie, who, before Hunky Dory, was a fey folky, struggling to find his artistic identity. I first met him in the early nineties when I was sent to interview him in a studio in Chalk Farm. He was doing a lot of press for his album Black Tie White Noise and was worrying that his music was being forgotten. He told me he wanted to write music for film; intending to do so for The Man Who Fell to Earth, but had been too exhausted. We talked about Peter Frampton’s father, Owen, an art teacher who had taught us both at Bromley Technical High School, ten years apart. When we concluded the interview, Bowie asked, in his typically charming way, “Can I have your phone number? Can I see you again?”

Of course I never expected to hear from him, but during the next few years, he often rang me up when he wanted to talk, sometimes at two in the morning. I was a new father of twins, dressed in only my underpants in a freezing cold house when I got one such call. Bowie wanted to discuss serial killers which, for a time, was a subject he had become enthralled by. I was at a loss as to how to reply, but soon realised I didn’t have to say anything, just let him talk.

When we first met, Bowie had already read The Buddha of Suburbia, and had heard that the BBC were intending to do it as a television series.

I met him in The River Café to ask him whether he would allow the BBC to use his original music on the soundtrack. But he said to me, at cross purposes, “I thought you’d never ask”.

“Ask what?” I replied.

“Me to do the music for the TV show.”

That’s how it started, and he went off to Montreux, Switzerland with the tapes of the show. The late director Roger Michell and I flew out to hear what he had done. We sat in Bowie’s tiny studio with his then collaborator, Erdal Kizilcay, who played the instruments on Bowie’s eventual album.

At first hearing, Roger was disappointed, and was tasked with having to tell the world’s greatest pop star that he didn’t like his work. You couldn’t just write a song and play it against a film sequence. The music had to work with the images and the story.

Bowie took Roger’s complaints seriously, writing them all down in his little notebook with a pencil. He stayed up all night revising the music so that he could play it to us the next morning before we went back to London. It didn’t surprise me; Bowie was an autodidact and incredibly industrious, constantly trying to improve himself, evolving and experimenting. He had high energy and read widely, visiting galleries daily and surrounding himself with the most interesting people. He admired Prince for the sheer volume of his output. He used to say, “How does he do all that? He must be a cokey.”

The next morning, Roger and I listened to his revised ideas. They were an improvement; the sounds now worked better with the action, the music fitting the beats of the drama.

When Bowie finished the album, he came to London and invited my partner Tracey and me to his hotel to listen to it. When we turned up, he was dressed in a kimono, and presented us with two notebooks with The Buddha of Suburbia written as a heading. He was going to play the entire album to us through a small tape deck, and we were to make notes as it went. I immediately went into a panic and slipped into the toilet to smoke a joint.

Tracey and I sat through the album as Bowie watched us. I didn’t write anything down at all, but stared at the page, hoping something insightful and useful would occur to me. But it was a great record, and later David claimed it was one of his favourites. It was a relief to get out of that room.

I went through something similar with him later, when we were working on a theatre adaptation of Ziggy Stardust. As before, Bowie played the whole album while singing along to it and asking for suggestions about how we could stage it. I had no idea, and I don’t think he did either. He just wanted it to be ‘avant-garde.’ I said it needed a story if it was to be a theatre piece. He told me he didn’t want a story. And that, as they say, was that.

On August 11th 1993, the pregnant Tracey and I joined Bowie and his wife Iman in a limousine to see U2 perform at Wembley. The moment we stepped into the stadium everything got weird. A murmur became a roar as people began to recognise him; ninety-thousand heads turning, like a wave, straining to see the nation’s greatest pop star, and perhaps wondering who the diminutive Indian scampering along beside him was.

This was the night when Salma Rushdie, still in hiding after the fatwa, and wearing devil’s horns, was invited on stage by Bono. Music and literature had come together, briefly.

Brian Eno had told us we should sit close to him at the mixing desk as it was the safest place to be in the event of a crowd surge. But the desk was in the centre of this menacing multitude. So, a dozen security officers formed a triangle around us and like an arrow, forcing us through the shrieking horde. I realised, while being carried through that immense crowd, that extreme fame was both exhilarating and terrible, though Bowie didn’t seem to mind. After all, as a teenager he had wanted to be Elvis.

Does this have to be your final piece on music???

Really enjoyed reading this. Loved the In My Own Words documentary screened the other night as well.

My first encounter with the music of David Bowie was the video for 'Let's Dance,' which I saw on Top of the Pops. The song was number one in the United Kingdom for three weeks. The video was one of those formative cultural experiences, where you know instinctively that there is more going on than your child's mind can grasp – a world that exists beyond the slender reach of your understanding. In the same way, I could just about fathom that 'House of Fun' by Madness (one of the few songs ever penned to focus on the social embarrassment of purchasing condoms for the first time) wasn't actually about hi-jinks at a fairground.

I was fascinated by the aboriginal couple in the video for 'Let's Dance', for whom a pair of red shoes initially exert an exotic allure, but later become synonymous with the city on the horizon that both exploits and oppresses them. By the end of the song, the shoes are a malign talisman to be stamped on and kicked around in the dust.

I asked my mother what the video was about. She told me that it was about racism. In hindsight, I think that it's more complex than that.

The eighties were a very strange time for Bowie. His mystique was on the wane, but he was probably more popular than he ever had been at any point in his career. The 'Let's Dance' album sold phenomenally. The two albums that came after ('Tonight' and 'Never Let Me Down'), which are regarded as among his worst, both went platinum. Strangely, in my opinion at least, his best songs from this period appeared on the soundtrack to the film Labyrinth, when he was unburdened of the pressure of being David Bowie. He could be someone else. He could be Jareth, the Goblin King with the spiked, lion's mane hairdo. The film yielded 'Magic Dance' – a bouncy, spirited back and forth between Jareth and his goblin minions. There's a song called 'Chilly Down' which Bowie wrote but didn't perform, where the easy-going Caribbean lilt of the music is unsettled by lyrics that hint at sexual coercion. My interpretation might be coloured by the way that it was used in the film: As an accompaniment to a disturbing scene where a 16-year-old Jennifer Connelly is harassed by freaky-puppets who are capable of removing their own heads, and who are very keen to remove her head as well.

By the late 1980s, Bowie could have added 'soulful gravitas' to the section on his CV where actors list the accents they have mastered. His other two offerings on the Labyrinth soundtrack are a pair of earnest ballads: 'As The World Falls Down' and 'Underground'; the latter elevated by that very distinct, booming, back of the throat vocal, that was the hallmark of the David Bowie of this era.

After the nadir of 'Never Let Me Down', Bowie attempted to recover his mojo as the frontman of a band called Tin Machine. I think that part of him would have liked to have been a performer in the vein of Iggy Pop, but indestructible warrior-poets of that stripe are born rather than made.

'Black Tie White Noise' is where it felt like Bowie was putting himself back together. It wasn't entirely coherent but he at least came across as re-energised. He delivered a cover version of Nite Flights – one of four Scott Walker offerings to grace the final Walker Brothers album; an interesting choice of song, given a new funked-up direction by Bowie and Chic's Nile Rogers. Scott Walker, for all his talents as an existential songwriter, never really had it in him to bring the funk.

The Buddha of Suburbia album strikes me as Bowie reconnecting with his origins, along with the more artistic side of his nature. I suppose that you could draw a comparison between this record and the Labyrinth soundtrack, in that it is tangibly related to someone else's project and perhaps that freed him creatively.

These past weeks I have been rebuilding my Musicbee database which has been corrupted through my own dumb actions. I have been cleaning up the broken links and dragging hundreds of files from one dialogue box into another. It is slow and tedious work, but necessary if I want to listen to music on my PC.

Along the way, I made a re-acquaitance with Billy Idol's 'Cyberpunk' album – a sprawling conceptual record that marks a dramatic shift in style from rock cabaret towards dystopian electronic soundscapes. It was a critical and commercial flop that almost tanked his career. Despite the derision that greeted the album upon release, parts of it have aged very well and even feel contemporary. It's hard work for sure, but interesting. For example, the last three minutes of 'Adam In Chains', once you get past the interminable self-hypnosis tape intro, are recognisable as Billy Idol but in a new and unexpected guise, at the helm of a somnambulant ballad with electronic stopwatch percussion that reminds me of Propaganda's 'Dream Within A Dream'.

My theory is that Idol – a man who, prior to the release of 'Cyberpunk', never encountered a problem that he couldn't solve by yowling at it like a Californian mountain lion – would have been given an easier ride by the critics if he had recorded the album in German. They would have called it a sci-fi masterpiece and hailed its creator as the Tarkovsky of punk.