Dear Readers,

What a joy it has been to read through this dazzling array of stories. Over seventy entries this time—the most subscribed competition yet—each one crafted with care, imagination, and flair. I am truly impressed.

The standard has soared even higher, making this the most challenging competition to judge so far. Writing is never easy, and every submission is a testament to your creativity and dedication. Thank you for sharing your words; your passion is inspiring.

The winning stories are vibrant, surprising, and utterly original.

Until next time,

Your loving writer,

Hanif

FRACTURE

L.A./1969

I was making money, don’t ask how, but enough to rent one room above a garage in west L.A. I had split from Dennis but took his painting of naked ladies as a room divider between my bed and the front door. The walls were lavender and India prints and lace billowed around my bed.

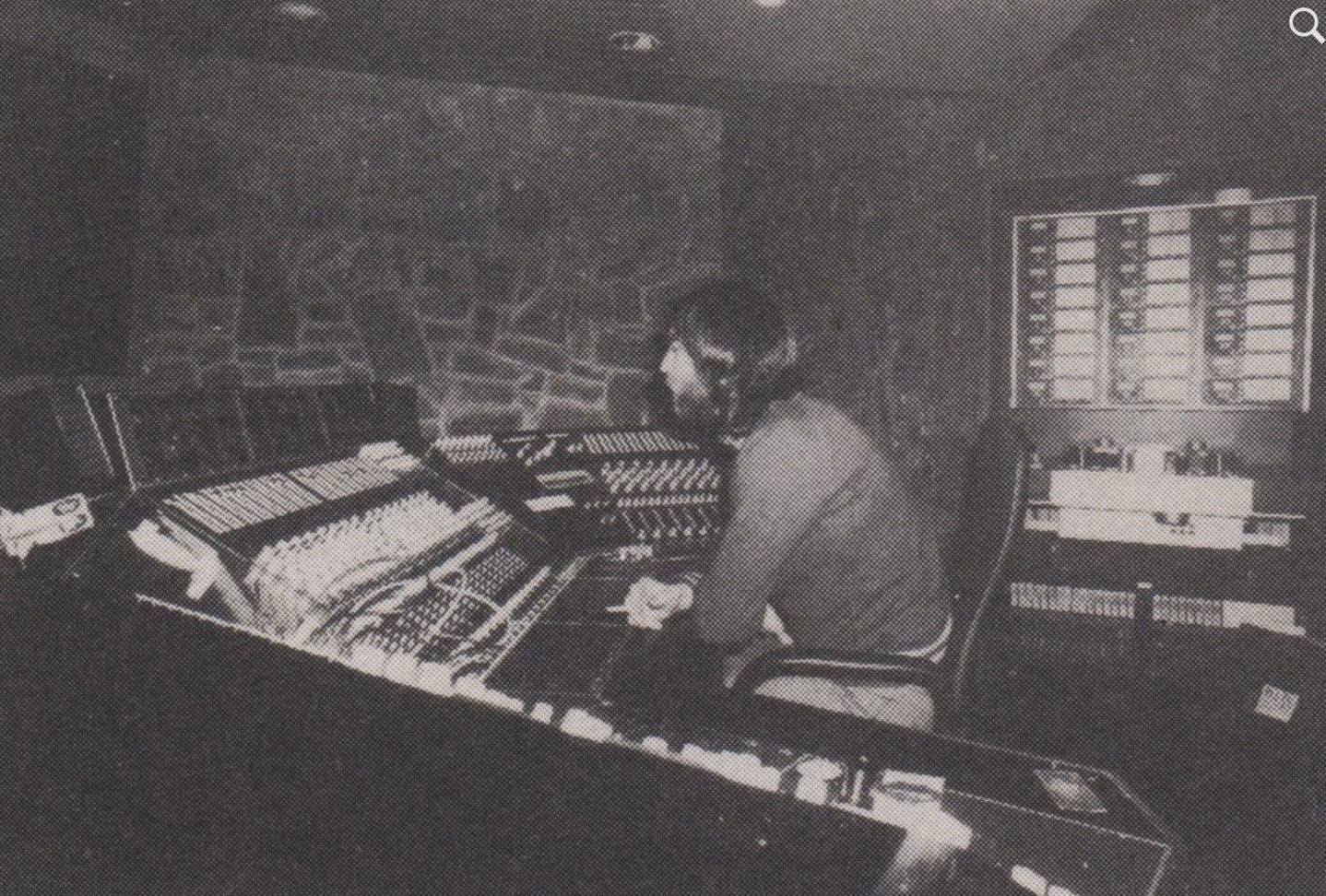

I was hanging out with a guy named Ted, a sound engineer. After I finished a job, I would go to the recording studio and stand around in the back while Ted worked the console. Behind the control board was a thick, glass window. On the other side musicians tuned guitars and techies adjusted gear and foam baffles. Ted sat in darkness; the musicians were lit. “Ready?”

I thought all a girlfriend had to do was be cute and quiet. Presence was enough. I didn’t have to talk. In fact, in Ted’s control room, you couldn’t talk. But the scene outside the studio; in the hallways and stairways, was a crush of agents, musicians, and groupies, hustling to score.

Ted was cold and quirky and British. There was something about him that was faintly repellant, and his respect for me wouldn’t have budged a needle on his console. I thought he thought I was a bit of hippy trash. He had no measure of me; my inner life was sealed off, even to myself. I had long, sun-streaked hair, black eye liner, a mini dress and bare feet. I was an easy laugh, I liked the intoxicants, I liked to party. I was a good enough girlfriend for the short term, he was a good enough boyfriend.

Until I met Geoff in the hallway. He was the bassist in the famous band that was recording in Ted’s studio. Our eyes kept finding one another and finally I moved close and asked him if he wanted to fuck. We left in a car full of bandmates and at Genesee Avenue just the two of us got out and climbed my wooden staircase to the billowing India prints.

I had another thing going on with a red headed biker from Texarkana. I kid you not. Can’t remember his name, it was a nickname, a biker nickname. He would show up from time to time, clomping up the wooden stairs and we’d get high and physical. I felt sorry for him. Why? I have no idea.

I was bored. Terribly, terribly bored. And numb. And dumb. And lonely, terribly, terribly lonely.

In my perpetual daze of numbness, some synapses connected; better get some birth control pills. I was also smitten by a married second cameraman and though things weren’t going well, the situation suggested that I should take the pill even if it did make my hair fall out.

The health care available was the LA Free Clinic. I wandered over there one summer evening and was given a cup to pee in. After an hour I was ushered into a treatment room by a Hollywood handsome doctor. He asked me why I was there, and I said to get birth control.

He said, “You’re too late for that. You’re pregnant.”

The shock left me in shock.

Some friends invited me over to watch the moon landing that night. It held no drama for me. A little astronaut had just landed in my uterus. I told them I was pregnant. They wanted to pay my way across the border to Mexico for an abortion. No, I couldn’t do that. I believed that if I went to Mexico, I wouldn’t come home alive.

Back in my apartment I listened to Joni Mitchell and daydreamed about a baby who would love me forever, who would become my best friend and my companion for life. I wouldn’t be alone, and I’d have a purpose.

So, I stayed pregnant, moved back to Chicago, went on welfare, and had the baby.

She was born early with hydrocephalus. She survived, and the plates of her skull eventually fused. In her early twenties she was diagnosed with schizophrenia, a not uncommon outcome of hydrocephalus.

I named her Bronagh; Gaelic for tears.

Who was the father? We will never know.

She changed her name to Deborah, the biblical warrior-prophetess, and married the mentally ill grandson of a holocaust survivor. Somehow, they survive, though they don’t thrive.

She calls me every day. Sometimes I answer, sometimes I don’t.

My companion for life.

ALICE PROGRESSES

Alice is laid out on the bed, her left knee bandaged and raised. Her right side is draped with one of those honeycombed hospital blankets that give off an odour of convalescence and disinfectant. I’m looking at her sidewise – an awkward angle but I couldn’t, somehow, bring myself to orient the chair so as to stare at her fixedly as if she were some injured bird I’d just brought in from the garden. Her body was damaged but repaired. War child that she was, she’d tried to tough it out until she’d been unable to get out of her chair and Francis, her husband, had no choice but to call 111.

I’ve called her Alice ever since she left (actually, was ejected and no longer thereby just a parent but to my mind a victim and besides, parents don’t act this way), her flame-red hair and her forest green Renault disappearing together down the road to parts unkown. I learned afterward she was having an affair with a lecturer with the requisite foppish trilby and a little MG. Only toward the affair’s end did he start taking open-handed swings at her, blurry with scotch. That was back then. Now I don’t quite know where that woman, that person, that parent has gone - or mostly gone. Is that a distinction without a difference? Gone or mostly gone. Can someone continue to be who they were just some of the time? Lately, she’s become at times foul-mouthed and irrascible, muttering as she processes around the house, bent over shuffling in her nightgown, lining up old medicine bottles, pens, silverware as she sifts through her life’s objects, sorting friends, acquaintances, family members according to their present value: sons, lovers, friends, husbands, mothers-in-law, and those who emigrated or just drifted away. Now and then she’ll launch a barrage of text messages – florid with accusatory pronouncements in a sanctimonious style not authentically hers. I read them, reluctantly, compellingly, and then I must sit and breath out slowly to dispel the bolus of rage, sadness, and shame and what else besides. Then I remember how it was when I decided to exit my own marriage when the nightmare of conflict and rage didn’t seem to be tapering. Distress has a way of shifting us subtly into another dimension: we’re permitted no longer to be of the world; we find ourselves on the other side - an isolation ward to keep us, and our pain, from leaking out into the world.

And it does seem a little ironic, looking back, that at the very moment my father began flinging those suitcases down our stairs my stringy little nubile self lay stretched out on the dining room floor listening to that unforgettable staccato theme of Jaws on my record player? Cut-cut - cut-cut -slash-slash–rip-rip. Unexpected dismemberment from below. The end of tomorrows being much like todays.

Our sporadic conversation finally peters out. I have my phone with me. I check my email and watch a video of a glacier collapsing in Chile nineteen hours ago: small mountains of ice shearing themselves off, easing themselves into the water like cautious winter bathers. The tumult, the irreversible loss of form and dignity feels haunting and poetic, a slow but violent dance and then it is done.

The surgeon appears, jaunty and solid. “Hello Alice. How are we this afternoon?”

“I’m okay, yes... . I think,” Alice replies faintly.

“Well, don’t worry. We’ll have you out of here soon I should think. Sit tight for now.”

I notice the golden hour sunlight has crept across the pillow on which Alice’s head lies. For a moment it irradiates her hair.

There is a photo of her somewhere, seated on the grass, intent, silent, entranced by the distant Malvern Hills she adored. Well, adores still. Finding herself as a woman; too late; energetically; clumsily; hurtfully. Hurtfully, let’s be clear. And yet my later self - the one who replays over and again those tumbling suitcases and the door banging shut kicked from the outside and the dismal never-ending Sunday afternoon visits - can’t help but posthumously cheer her on for escaping them both, the husband, and the lover. Only now to lose herself once again. We do, we so do , spend a lifetime learning how best to live our life before it’s rudely yanked away. Mistakes are inevitable.

The duty nurse swishes back the curtain: “How are you Alice, you alright?, she says. You’ll be going home soon.”

DIVIDED

Terry had not ventured down into Tanhill Valley for years. “Full of poncy f****rs and students now” was Terry’s opinion of it. He preferred to spend his days drinking on the local high street (‘The Road’) that lay cut off on the other side of the bypass. This street, once a thriving shopping area, had become notable for graffitied shutters, pubs with chipboard windows, and mingling groups of the drug-addled and permanently drunk. As The Valley thrived, The Road was dying.

Terry had been drinking solidly now for three days since his father’s cremation and had been ejected from even the high street bars. Since the cremation, he had thought about Tanhill where his father had worked in a small scrapyard. Barred from his usual hangouts, he bought some cans and decided he would go to the valley to drink and reminisce; he felt the need to be near where his Dad spent his working and drinking days. “Why shouldn’t I? I’ve got the right to be there.” he said to himself. “I’ll lie on the grass with me cans.” He thought he would try the Boatyard where his Dad had bought him his first pint at fifteen and drink to his memory.

On the steps leading down to the burn he sat and rolled a cigarette and clipped open a can. He looked down and took in the scene. He recognised the old warehouse, now converted into artist studios; a bistro that was once the mechanic workshop and the cleaned-up Boatyard.

Terry had always thought and dreamt about this place in monochrome and browns. Now he saw it in colour. It was leafier than he had remembered it, with an abundance of wild vegetation and flowers. Trees overhung the burn; Terry remembered that the Gut, as it had been known, used to be lined with columns of tyres and car parts. It used to fester - black, oily, menacing, too ill to move toward the river. Now it flowed healthily toward the river.

Here Terry had grown up with his friends from the estate exploring the old tanning yard and the iron smelter with its rusty, lethally jagged equipment. They used to look for danger and adventure; played ‘dare’ across the old mineshaft or over the Gut; broke into land fenced off for contamination; chased the Gut rats with bricks. By the burn was the spot where one evening they found the body of a man who had jumped from the bridge spanning the valley; for weeks he had nightmares of the wizened face, spatula teeth and bent-back limbs. In his teens, it was the place where they hung out with girls. At the back of the tanning shed, now a micro pub, they had built an elaborate den, with mattress, chairs, a brazier. Here they all at some point lost their virginity.

Terry slowly made his way down the steps to the Boatyard. Coming through the speakers there was the sound of a young woman singing, accompanied by acoustic guitar. He could smell spices, chargrilled food, bread, pizza; as a kid it was the smell of oil, burning rubber, rat piss, paint with the invigorating sound of crashing metal, drills, hammering.

Outside the Boatyard the beer garden was full and vibrant; laughter, gushing conversation from the young, vibrant and hopeful. A few of them had noticed Terry as he approached the garden entrance staggering with can in hand. The bouncer by the pub door, who had also spotted the dishevelled and staggering figure, straightened his back and, with wrists crossed over his crotch, went to face Terry at the entrance to the beer garden.

“ You alright mate?”

“ Aye, just leave us, I’ll be alright. I just want a drink.”

“ Sorry but you can’t come in here. You’ve had enough. You’d better get off home.”

“How man. I used to drink here with me Dad.”

“ Well not tonight you’re not.”

“ Who are you like? You weren’t even born when I used to come here man.”

He threw his can toward the bouncer. This action threw him off-balance and he fell full length on his front. He lay like a religious novice prostrate in front of an altar.

“Come on mate, you’ve had enough. Get yourself back to where you belong.”

“Where I belong? You cheeky bastard. I know one thing …. I don’t belong here anymore. Full of tossers.”

Terry got up and made his way back to the bypass.

FRACTURE

Adam had been driving for days. Outside the dusty windows of his pick up truck, the fields had changed from corn to rape to cattle to wide blue yonder and back again. His fat companion, Chito, a dog of inexact breed and taciturn nature, occupied the passenger side. More often than not, he was asleep and snoring – his drool freely laminating papers and maps and electronics.

Every so often, they pulled over to answer the various calls of nature, but mostly they drove – because Adam had somewhere to be and he had to be there before it was too late.

He was headed for a little town called Fracture, and it was a difficult place to find – but everything depended on him getting there in time.

Adam was, by trade, a seeker after mysteries – a job made possible by youtube – like everyone in the 21st century, of course he had a channel.

His channel featured him and his best friend Vesta, travelling around, filming themselves investigating mysteries.

They started with the usual suspects – bothering poor old Bigfoot, raising ghosts, visiting UFO hotspots. They were amazed when it took off, delighted that you could make a living by having fun with your friend. For him, it was the joy of being with her.

It was the same old story with them – he loved her but he pretended not to because he was scared of wrecking what they had and because, at heart, he was probably a coward. He was always going to tell her but then, one day, doing research for their next video, Vesta disappeared, and the bottom fell out of the world.

The last time he talked to her, she was excited – she had found a new mystery – she was going to check it out. It was all to do with a little town called Fracture, out near enough in the middle of nothing. Wasn’t on the map. You had to get to near it and then ask the locals. But she had to go today- couldn’t wait for him to come down from college to join her.She said if she was right it would blow his mind. He was hurt and abrupt. That was three years ago – she left to drive to Fracture and never came home.

And that was how Adam truly became a seeker after mystery. He began to piece together the secret research she had been engaged in before she left. Vesta loved strangeworlds – would talk to anyone, crawl into any fissure in pursuit of the inexplicable. She lived for the world between the lines.

As he began to understand what she had uncovered, his mind boggled. He would have dismissed her theory out of hand, except that no one could deny that Vesta was really gone. Didn’t the very fact of her disappearance give credence to the whole idea that there might be something hidden that should not be uncovered in the town of Fracture?

Adam began to believe that he was the only one who could find her and that by doing so he could save them both.But to save her, he needed to find his way to the place where he believed that she had vanished - and he had to find his way there tonight.

Outside the buick, the dying sun had pulled the colours from the land and everything was sepia and somehow drained. A hundred metres down the road, a man was standing in the front yard of a wooden house in the shadow of a persimmon tree from which he was eating the fruit.

Adam stopped and wound down the window,

“Can you point me in the direction of Fracture?” he asked. The man took a bite of fruit. His grey eyes were narrowed but not unfriendly. Chito stirred in his sleep and his paws jerked.

“You sure that’s where you want to go?”

Adam nodded.

“Well, keep going, son,” the man told him, “The signs will appear when you get close. But you’re cutting it fine.”

A few miles more, and Adam finally saw it - Fracture. It was already beginning to become insubstantial, like the heatwaves from fire. Adam gunned the engine and flew into town. His heart leapt as he saw a girl with raven hair, raising her hand in delighted greeting.

“Adam! You made it!” she screamed and began to run to him-as the whole town and everything in it disappeared through another fracture in time to travel to who knows where?

BREAK

“Fracture eh?...”

He chuckled….

“wtf?” I thought. Yeah I did actually think that, probably in this faking typeface …Faking? ”Fcking”, I think, but autocorrect wouldn’t allow me the screaming replacement!! Daft can’t!... sheesh…

Faking indeed… I can spell ya donut, jast canny type straight… I am in your world now ain’t I?? ’Sup AI? Can’t swear yet?? Jesus, catch up dickhead, beating Magnus at Chess is shit hollow if you cunt manage swearing..

Swearing.. We English excel at it…. spesh with a shandy in us and a belly full o bile and a wiggle in our stride…Scottish are world champions too. Broad blade profanity. Americans can Ssshyyyyyitt!!” all day long, but can’t “cunt” for love nor money…

Expressions.

Moons passed… in a kitchen prepping for corporate events’ Christmas do’s. One of the chefs breathlessly reporting “…just seen one of the Coors breastfeeding..”

Yeah right, Deutschebank. Spunking holocaust gold at the Coors for their Christmas do… Fuck sake, we’re in YOUR world now ain’t we?? The fuckin Coors…. Shit me.

Money, is that IT??…

Like a heartbeat drives you mad.

….summed up perfectly by a French Chef, said to me “ I love how you English swear, you even swear in the middle of a fucking word! “absofuckinglutely” he said and chuckled..

Shit, where was I…?

Yeah…”wtf??” I thought… this is no situation worthy of a chuckle, inappropriate at best, downright unprofessional one might say, maybe just trying to put me at ease, but seemed too casual, too bored with my predicament to really care, or maybe just jolly?

Sanitised gallows humour in the post -hangin’ age.. I had friends at Med school.. ‘Ash cash’ they used to call it, getting paid for a stint on the incinerator.

Threads. Broken. Joined.

All the accidents are real, a coupel are fakes, but mainly shit typing trying to get the words out before they exit forever.. Don’t even know what I stand to gain… a thumbs up emoji?? A prize? A pat on the back from a well-respected author who is lying in a bed unable to move his body and is somehow still writing… still creating…still surviving… shit… “ A pat on the back..” sorry mate.

I feel callous now as these harsh words spill out, but spill they do, a train of thought with no brakes.. I don’t even know his work, lazy reader notwithstanding, just clicked on his substack amongst all the other shit now cluttering up my inbox that I feel duty bound to get through..

I’ve started writing the end because I had a good last line I didn’t wanna forget…shit, now I’ve got to steer the fucker.. break the train…

Freedom. Inhibition.

Still, I’m not the poor fucker who cannot move …one fine day… Praying for science fiction to slam the brakes on and get rear-ended by the present in a staggering cacophony of shattered glass and airbags and hope that one of the broken collarbones is the miracle that can give him his body back…. Sorry pal, Sci-fi is a thing of the past. Ask Lazarus.

Shit, I’m sorry man, you’re living my worst fear, but how the fuck would I know?? You don’t either I guess.. trying to make sense of a second that has been split by a life.

And what you had. And what you’ve lost.

Your son, literally lending you a hand.. Your hands, holding his tiny body, blinking. Lovingly you wipe your tear from his forehead lest it roll into his eye and birth a tear of it’s own.

Moments. One inside the next.

Hands. One holding the other.

How many other people lost feeling that day? It was just a day after all. Something happened. Somewhere. Seemingly….SHIT, we don’t know anything do we?

At the exact same instant a heart somewhere exploded with the thrill of first love…

An acorn, trampled by chance into a goldilocks mattress of worm filtered loam began to unfurl it’s green aerial through the sharp, damp, leaf litter eiderdown, and in the snap of a century laid down it’s mother’s bed for its own scattered infants..

Better get back to the story, go back to the beginning… the French chef…no, before that..

Before. After.

There is no Time.

Shit…7.32…I’m larte for work… back to it tomorrow.. Stay the fuk out of it autocorrect.. You’re in my world now… Eight words left.. What to say? And how?

I remember saying, “…I think I’ve fractured it..”

“…no, my friend, he chuckled again…THAT… is broken.”

SLAB CITY

I met Calila on my first trip to the city, and I liked her, though I felt I shouldn’t. Calila was seven years my junior: she was sassy and sharp and had a vulnerability about her. She had a volley of orange curls and eyes like a bush-baby and she didn’t shave her armpits. I had never been to LA and always thought it wouldn’t be for me, but her corner of it was nothing like the one you meet in movies. Ramshackle, cosmopolitan, it was woven from bars and taquerias with hoardings above shops that said things like ‘Owl Rexall Drugs’ and ‘Zendaya is Beautiful.’ Her house on Snug Street was shaded by rows of mountains that receded into the sky in a belt of chevrons.

Calila had moved to LA to join a lab working on a new model for measuring patterns of climate. She was ambivalent about it: she kept saying she wanted to write a novel. We got breakfast at a Guatemalan place and she buried her face in her hands as she told me that the ecological costs of their research were huge – the stacks in the data centres that run these models were hot, hungry monsters sloshing away hundreds of thousands of litres of water and burning up millions of megawatts, even for simple calculations. “We’re creating the harm we’re supposed to counteract,” she said. I moved my beans across my plate. Her curls spun over her shoulders; lifting her head, her eyes teary, the overhead lights reflected in them like a row of planets.

Moses had lost his house in the fires and moved into the shed at Snug Street, he’d been there for a few months when I got there. A forty-something Mowgli with frosted tips, he’d lived in London for a few years with his half Sierra Leonian, half English aristocratic girlfriend – a far cry from the Moreno Valley where he grew up. He caressed his stomach as he talked, his torso tattooed with a fiery ball that he said was Venus devoured by her own gases. He’d met Saskia learning portraiture in Florence: the house was littered with canvases of dramatic chiaroscuro – simple, disturbing compositions of waxen bodies and rotting fruit.

Moses brought us to a party in the neighborhood that evening. A wind collective called ‘smogg’ played free jazz in the lower reaches of a fig tree. I was sitting next to a German dude who said he used to work for Tesla. Unripe figs lay about like bullets. Split tones floated over me on the blanket as I caught the eye of a fat bird, like a mutant robin, meters away: we stared at each other a while – when I cocked my head to the left, he followed me, and again to the right. We danced like this, back and forth, for some time, and I felt happy I was born.

A fly was buzzing in my ear, but I barely registered it – I could feel Calila’s arm-hair on mine as she laughed at our choreography. When the music ended, she started to tell me about Slab City, an off-grid town by the Salton Sea which Moses had taken her to see a few weeks before. Once idyllic, in the 1980s birds and fish began spontaneously dying when the pools began to collect toxic runoffs from nearby farm-holds; now only vagrants live there, and in the summer it reaches 120. In East Jesus, walls of green and white bottles and sculptures made of trash strew the desert. One man has encrusted a hill with a kaleidoscope of latex, concrete and adobe, and calls it Salvation Mountain. God is Love, it reads.

We left at dusk: Moses drove us to Koreatown, where high-rises embossed a lurid sky. These buildings feel so recent, a tenuous mesh of concrete and clapboard, and as we drove through Skid Row, we passed thousands upon thousands of people living out of their cars. Moses said the palm trees stubbed across the city were reaching the end of their natural lives – low dwellings were slated for reinforcement or else they’ll be crushed. Cackling, he muttered something about Chicken Licken – the whole city, Moses said, was built over deep fault-lines that made places like Beverly Hills and Altadena, just razed by the fires, some of the most dangerous and unsuitable places in the world for building homes.

We’d heard of a new spot for dinner, and when the car pulled in, we joined the line.

Dear Hanif

How unexpected but longed for - an affirmation of my story. Thank you. May you heal completely and continue to write out your singular, illuminating thought pieces. With love, Sharon W.

I enjoyed reading the stories. Congratulations to you all!