Dear Readers, a small note before we begin. Since my accident in December which left me without the use of my hands or legs - a considerable inconvenience - I have been writing, via dictation, a weekly dispatch, which you all read and respond to with such love and thoughtfulness. You have kept me a live. As we approach six months, I kindly ask that if you have the means, it would mean a great deal if could support my writing by becoming a paid subscriber, and keep this show on the road.

Of all the questions authors get asked, the most puzzling but persistent is what others might think of what the writer has produced. These potential disapprovers could be the writer’s spouse, family, colleagues, community or neighbours. It doesn’t matter exactly who they are. Yet the question of these opinions is clearly a crucial one for apprentice artists. When they begin to work a chorus of censure and dissent, if not of hate, starts up. The writer becomes inhibited by concerns about the effect his or her words might have. The writer could become anxious, stifled or blocked. They could begin to hate their own work, or become phobic about beginning.

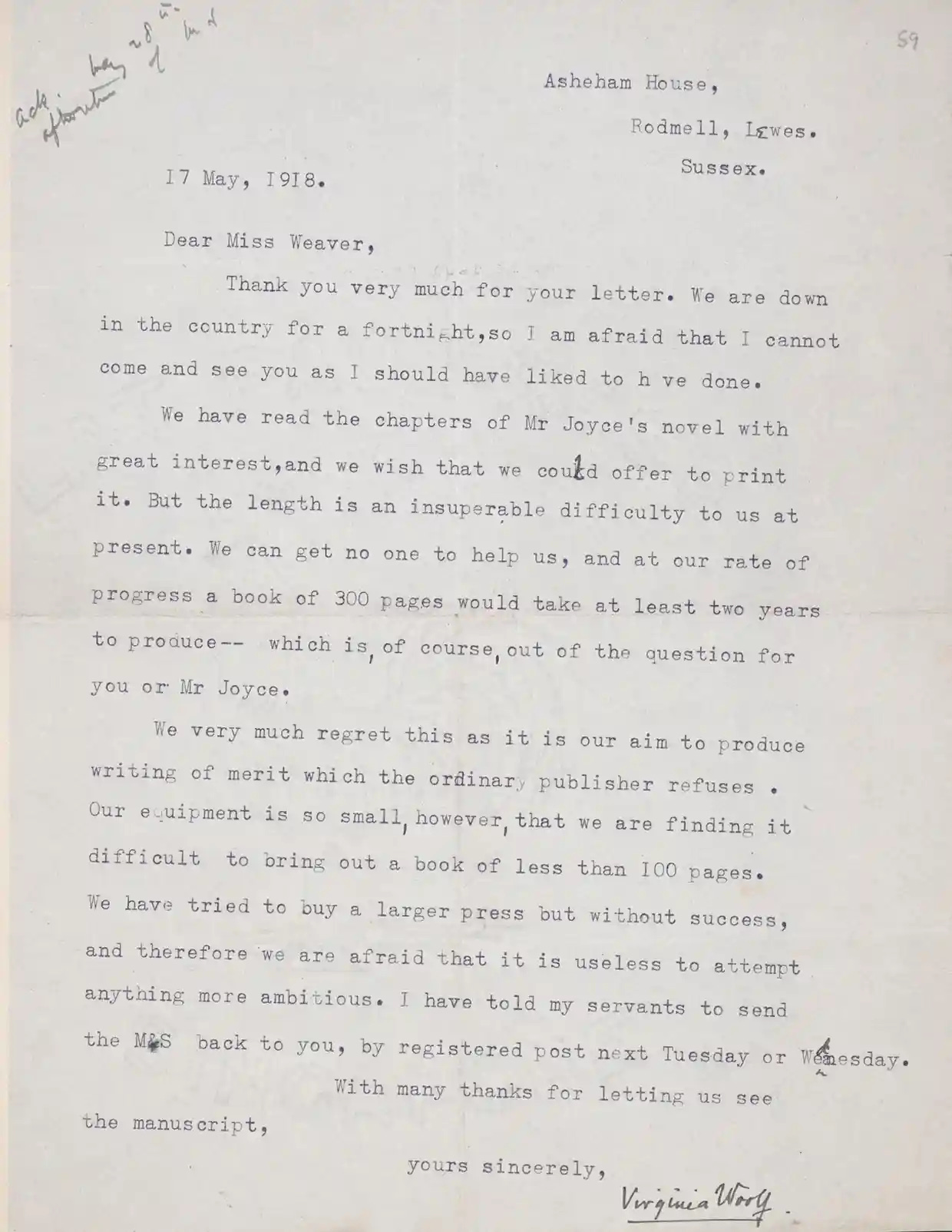

Materials put online by the British Library this week detailing the lives of 20th century writers are testament to this; we see TS Eliot worrying about The Waste Land – “I do not know whether it will do, and must wait for Vivienne’s opinion as to whether it is printable …” – and rejection letters to James Joyce (from Virginia Woolf) and George Orwell (from Eliot), which show even these literary greats had to overcome early criticism and disapproval of their work.

Here the artist is generating a kind of lurid fantasy, and not one that is of use. In truth, when you begin writing you will have no idea what anyone will think. If the writer has some level of integrity, he or she will always do her best work and will eventually discover whether others are indifferent, wildly enthusiastic or something else altogether. But the assumption of the nervous writer engaged in this doomscript – this omnipotent view – is that she has already aggressively provoked or hurt someone. Not only that: these “neighbours” will retaliate. There will be guilt and a terrible conflict, so why bother at all?

This rigmarole implies that words are dangerous – that they can upset, thrill, provoke and change lives, which is useful knowledge. Good writers are aware that they work not for themselves, but to do something to a reader: words are powerful magic which must evoke strange and terrible worlds.

But what of these “neighbours”? What are they doing in this internal scenario? Will the wrong words persuade them to abandon you? François de La Rochefoucauld describes this fallacy well. “That which we call virtue is usually no more than a phantom formed by one’s passions.”

From one point of view, this virtue could be called conscience. To put it kindly: here the writer is considering others, and how could anyone argue with such benevolence? Nevertheless, conscience is a less effective description of what is taking place than the notion of the superego, an idea Sigmund Freud developed after the first world war, linking it to hate, depression, masochism and what he called the death instinct. Conscience implies concern, if not decency. The notion lacks the devilish, if not sadistic dimension that the idea of the superego has, where the “good” becomes an obstacle to the truth. It is not that the writer has committed a crime of speaking, but rather that she is already guilty and always will be.

Ultimately this is not a moral question about doing harm to others. It concerns self-harm, the enigma of self-persecution and how you can begin to fear your own imagination. The writer might be a voyeur who likes to exhibit herself. This is partly what it means to present something to an audience – the wish to be known, to inhabit a persona, accompanied by a certain shamelessness.

But even as we speak we also wonder if we are more monstrous than we can bear. We believe that if we were good we wouldn’t have aggressive or violent thoughts, forgetting that monstrousness is useful in art, which, to be effective, has to be pushed to an extreme, making the audience tremble. Art emerges from what Friedrich Nietzsche called “inner anarchy” and never from so-called decency.

A critical faculty, one of judgment, is essential. Any artist must be able to look over their work with a clear eye, reading it through and dismissing this or that, and retaining the other. But the form of ferocious superego activity that Freud noticed is not part of the interesting difficulty of the work. It is not part of the struggle all artists have with their material and subject. It has nothing to do with the engineering of art. It is outside it, throttling it before it begins, telling the writer that she must always produce brilliant work and that she cannot make mistakes or endure failure. It is only destructive.

But why would anyone have such a killing machine inside them? For Freud, one of the most fascinating and impassable enigmas was people’s self-destructiveness, their masochism and their sadism. Indeed, he called the death drive “mysterious”. And you only have to look into the mirror to see it.

The ears have no lids. It is not just the so-called mad who hear voices. Who isn’t possessed by them? The superego isn’t just an obscure psychical function, it is more like an involuntary voice of command, involving a threat which states that if you think or do a particular thing, you will be punished. And imagined punishments are always worse than the real thing.

Not one of us didn’t spend years of our young life under the command of others, an order of adults who guaranteed our safety. It is important not to forget the sheer amount of fear all children endure. So the origins of this ever present threat are our parents and other authorities, plus the fury we felt about their instructions.

This internal social order is a narrow zone within which disruption and unpredictability – speaking or writing freely – is continuously punished. It is hard work being an oppressed victim of your own internal savagery. Parent-like, the superego appears to provide a form of protection, a limit, a boundary. But this promise of stability is of less use to the adult artist who must work with uncertainty, clearing a path for the new. You’re in a dark forest with just a torch. If you know what you’re doing, it isn’t art.

Liberating oneself from self-slavery cannot be a permanent achievement. But good things get done, terrors are overcome, guilt is borne and these self-created phantoms are chased away, at least for a while. If we have some intimacy with ourselves it is possible to track these persecutions and dispute with them.

Knowledge may, on occasion, trump the promise of terrible enjoyment. The return will be a clear channel of good communication between the unconscious and the conscious. This is where the work is achieved.

Dear Hanif, I write but as a social scientist. I submitted my PhD and had a psychotic break which nearly killed me because it devolved into severe involuntary self-punishment. My PhD was passed with no corrections whilst I was devolving into madness. I had childhood trauma but had thrived in life until over the course of a week weeks it was all taken away. Doctors admit they can’t understand my case. What you have written here today is probably the truest explanation of what happened to me. It was all exacerbated for me by being at the time in avery conservative form of Christianity. I persecuted myself. The saddest part is that the psychosis has taken so much of the creative, alive and driven soul I was away. It’s hideous and I need to recover. A person cannot vanish from the world like this.

Yes isn’t the boy a dish? Great piece O Handsome Hanif. And hugely amusing to read dear Virginia slagging off Joyce. Well it was probably only in private that she said it was like a boot boy in Claridges squeezing his pimples. Or something like that. And Eliot! Wanted to make the Soviets a less offensive animal than pigs. Speaking personally I would have told the old pseudo to burn the Four Quartets. Keep it coming Hanif. I really look forward to each instalment love Nige