Dear Readers and Writers,

First and foremost, we’d like to thank you for your wonderful and elegiac short story entries. Over one-hundred of you contributed with the most beautiful, unreservedly personal stories from all around the world.

That you were all so willing to share your writing with us and the community was deeply touching, and we hope to read more from all of you in the future.

It’s said that there’s more that unites than divides us, and these stories provide powerful evidence for this. Love, trauma, grief, excitement are alive in every one.

Of course, it was impossible to choose one winner, and so tomorrow our three finalists will be announced.

Below are our runners up.

We selected these stories because of their strength of voice, economy of language and command of form.

We hope you enjoy them as much as we did,

The Kureishi Family.

NEOLOGISMS

“Waddletwat!”

“You’re Queen of the Waddletwats!”

“You’re Lord Waddletwat of Waddletwat Manor!”

Maureen Eagan and I had a game: we would make up stupid words and mock each other with them. We were Catholic schoolgirls on the precipice of our 14th year, and in the time honored way of all such unfortunates we avoided the oncoming freight train of puberty by acting like idiots.

The coup de grace flew into my head. “You’re Pope John Paul Waddletwat the 23rd!” which too was unfortunate because Sister Mary James Patrice was coming around the corner ahead of us. Her eyes were lasers. Her fury was such that she could speak but two words: “POPE…WHO?”

We were sure our punishment would be horrific and we were right. We were, twice a week, to clean the nun’s convent. On separate days, lest we have secret fun making more neologisms.

I was taught how to dust things that did not need to be dusted, particularly the wooden pews in the chapel. My last task before leaving was to take the little Dustbuster vacuum and clean the stairs that went up to the nun’s private quarters. But under no circumstances was I to even think of touching the top step.

The job wasn’t as onerous as it first sounded. I grew fond of seeing the elderly nuns sitting in the living room making doilies. They were cute.

One day, as I vacuumed near the top step, I heard a noise. I turned off the Dustbuster and heard sobbing. The nuns were all in the dining room, who could this be? Of course I went on the forbidden step. I found myself in a long hallway of a row of rooms with doors closed. Except for the one on the end from whence came the sobs. Of course I went to take a little peek. And what I found shocked me beyond words and left me breathless. I dropped the Dustbuster.

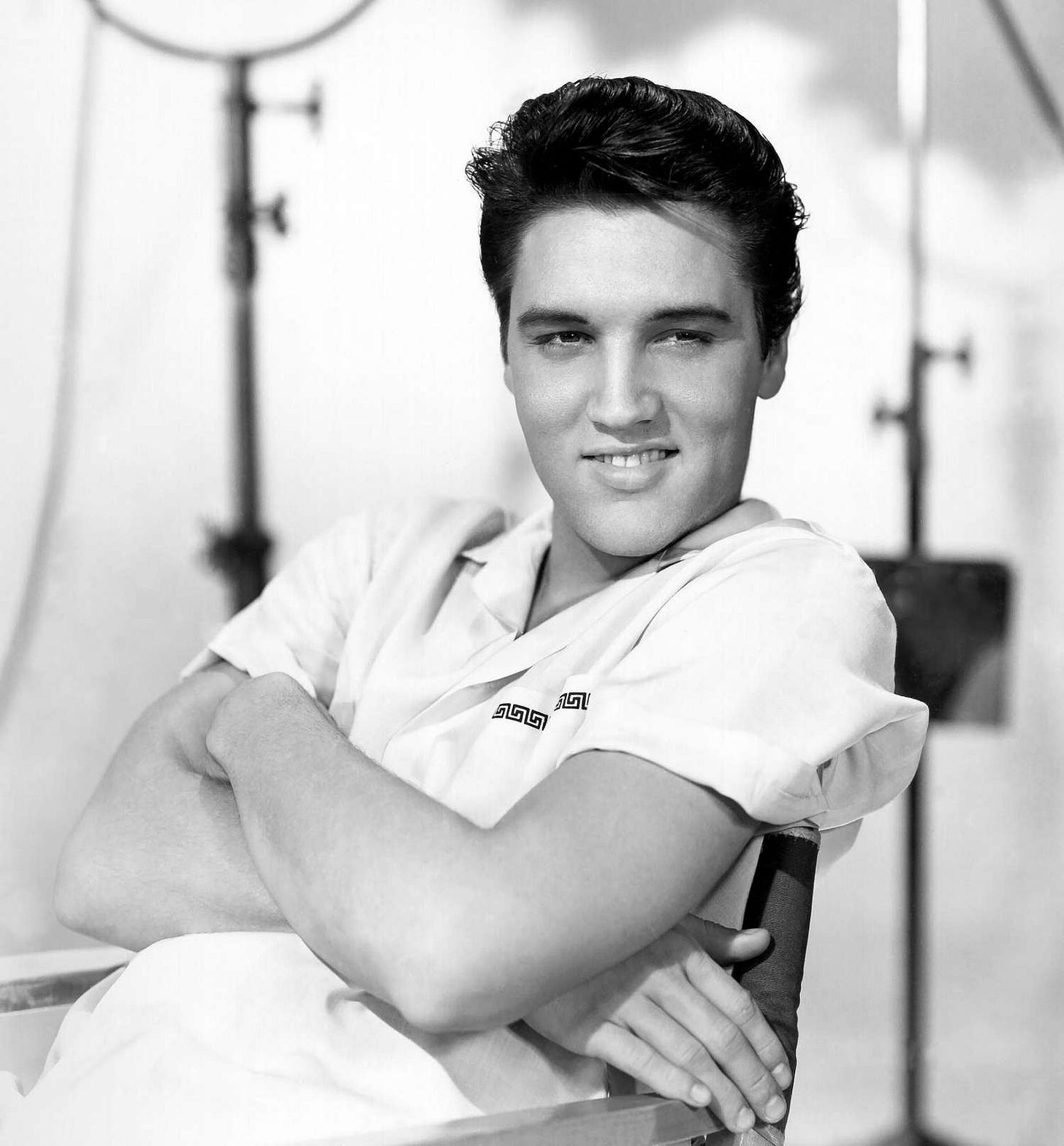

There was a nun with gray hair sitting on her bed sobbing, rocking and by all appearances praying, in front of – I swear to you – a velvet painting of Elvis. She had it propped it up on her dresser next to her figurines of the Virgin Mary and The Infant of Prague.

She threw Elvis back under her bed, pulled a tissue out of her sleeve and mopped up her tears. She asked the obvious. “What are you doing here?”

“I’m...cleaning.”

Her eyes flew wide with horror as she asked “You aren’t thinking of becoming a nun are you?” “NO!” I said loudly and with such conviction that she calmed down immediately. Curiosity made the words come unbidden. “Why do you ask?”

“Well, it was a long time ago, but girls your age used to enter the convent.” I may have acted the idiot but for a girl who knew nothing of the world, at times I was able to put things together fairly quickly. “A long time ago…like in the 1950’s? The nun’s lips tightened. I had no idea what to say next, so I blurted “I like Elvis a lot too.” Not entirely true, but I had heard Dad play Elvis when he worked in his garage. She gave me the side eye. “Oh yeah? What’s your favorite Elvis song?” I did what I always do when I felt awkward. I acted goofy. “Well of course, it’s Hound Dog.” I paused, trying to read the room. I couldn’t. So I bopped my hips from side to side and sang “You ain’t nothin but a hound dog, a-cryin’ on a tire” This sent the mysterious nun into paroxysms of laughter. Next thing we started a raucous singalong to “Hound Dog”. We got through the first verse and were happily bopping. “Well you ain’t never caught a rabbit and you ain’t no friend of mine!” Then I felt it. The long shadow of Sister James Patrice. Laser eyes. Could hardly form sentences. Finally yelled: “Get out of here Siobhan Kelleher! Get out! Don’t ever come back!” I went to grab the Dustbuster but Sister James said “Leave it! Just go!” The mystery nun said, “Listen to sister,” and I swear I could see the hint of a smile.

I ran down the stairs and out the front door as fast as I could. I ran until I couldn’t run anymore. Finally, panting with my hands on my knees, I found the words. The mot juste.

“Holy Elvis Jesus McFuckburger!”

LATEXES

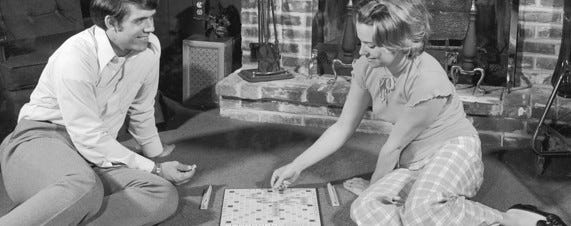

Latexes. He could play latex - if happy to leave fifty points on the board. Is latex a collective noun or a specific thing, some kind of plastic or rubber or other man-made material destined for landfill?

In his early thirties and these were the lengths to which he went to avoid having sex. To which they both went; it takes two to Scrabble. They could have sex and sometimes they did. It had been tentatively scheduled, as it was most Tuesday evenings, and that, perhaps, is why they chose not to. Sex was cold, as was the flat, and forced, until it became warm and easy. And it would after ten seconds under the covers, after the first lingering kiss, but, who has the patience? Scrabble would take an hour longer but would neither require any mention of psoriasis, except to challenge the spelling, nor require an unwanted core workout. Scrabble would not make it hard to put his boots on in the morning.

This was easier he told himself, if not in this precise moment as the questionable word overrode his ability to see anything else on the tile deck.

He considered floating it aloud but knew this would bring immediate challenge. A confidently played word could sneak under the radar but prior-warning would elicit a defensive response. If he’d had the required audacity to go for it, without consideration, the Scrabble board would still be nestled in the TV stand and they would be lying together, naked, flushed and spent.

It had always been this way. They were better, he thought, than young lovers. Better because the connection between them was seamless. Two that did not need to become one but had practically been one from the start. Sure, they’d bought under the bed restraints early on, they owned a ‘massage’ wand. He had even suggested they try out a strap-on on him before it arrived in an unmarked box, lest the neighbours sign for it, and it had turned out to be an order of magnitude bigger than he could accommodate. He could feel his piles burn at the thought.

They could have sex. They were just no more defined by it than they were by sitting in judgment of other patrons over a pint, cooking a five-dish feast from scavenged online Ottolenghi recipes or by planning trips to the concrete capitals of the former Soviet Union.

He was thirty points behind with around twelve tiles left in the bag. The big hitters were all already on the table, barring, of course, the ‘X’. The fifty-point bonus for playing his whole hand was likely to be the difference between winning and losing. It was now or never.

Her hand was moving to the official dictionary before he’d finished placing the ‘L’, building backwards, as he had been, from the adjoining plural he’d created on the board in as quiet a flourish as he could manage. It isn’t possible to play all of your tiles without some ostentation. She opened the book, flicking through the pages and skimming, skimming, skimming until she was deep in the LATE-s. Her face inscrutable she gently closed the dictionary and stood offering him a hand. A smile was creeping across her face as he took it and she encouraged him up and off the cheap IKEA chair at the kitchen table.

She kissed him slowly, her hand drifting to the back of his neck and up, through his hair. A Tuesday evening kiss. She led the way, the short distance, to the bedroom and pushed him down onto the bed before retreating to the bathroom.

This was good, he thought. When one schedules an activity, one should follow through, it was the whole point of scheduling. Sometimes you don’t know what you want until you start doing it. He undressed and laid back down. He could hear her in the bathroom as he felt at the scabs on his back. He resisted the urge to pick at them, the bedsheets already dotted with blood from ill-discipline.

The toilet flushed, the sink ran and the door to the bathroom closed. He turned on the bedside speaker and put on an algorithmically generated playlist. He made a mental note to try and improve the playlist quality for next Tuesday.

She smiled again as she joined him under the covers and he knew two things for sure: He was still in love and you can pluralise latex.

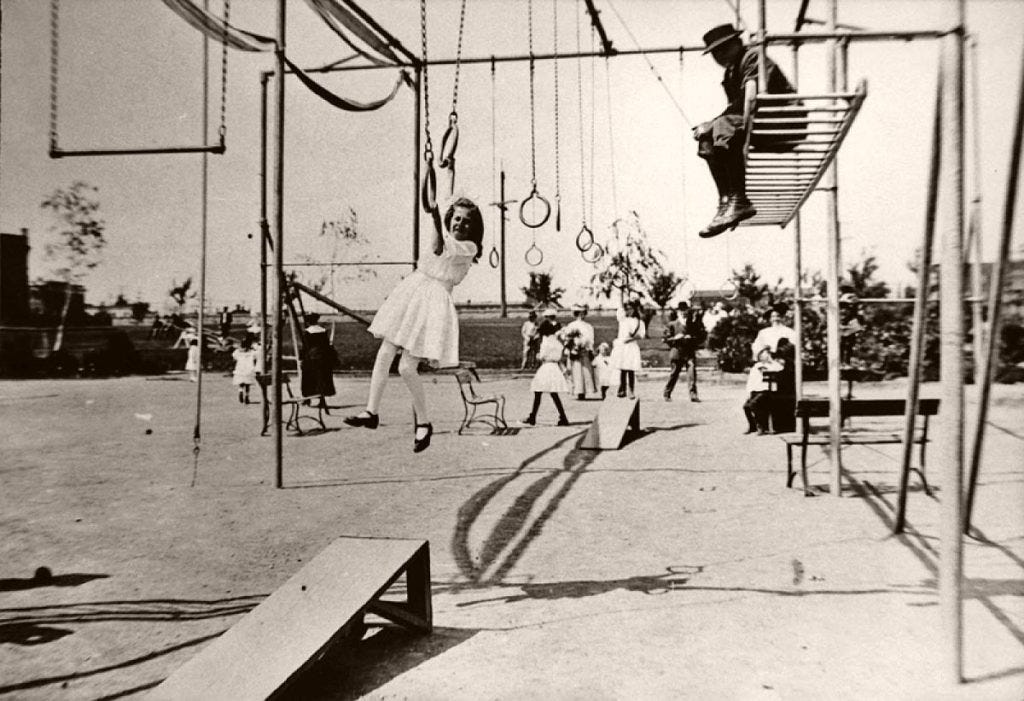

CRAZE

A new playground craze would bubble up from nowhere. First it was French skipping, then jacks, then two hard balls on a string that the girls called clackers and the boys called knockers, and then it was whirlers which looked like plastic elephant trunks and girls would twirl them round above their heads and the whirlers made a noise like a quiet scream. Then, as mysteriously as it had arrived, the craze would fade away. It was hard to join in if you didn’t have any jacks or clackers or a whirler – which Annette didn’t because, as her mum said, they had no money to throw away on passing fads. And hard when you didn’t have the guts to say, ‘Can have a go?’

After the whirlers came the hitting craze. It was the summer term of Annette’s second year at junior school. In the playground’s shelter, and over at the far end of the tarmac, girls and boys would say ‘give me your arm’. They would roll up the sleeve of the victim, hold out two fingers like you do to make a gun, they’d lick these fingers, then thwack them down on the bared wrist. It was called a Chinese burn. Annette watched from a distance.

The hitting craze spilled into Annette’s home. Morecambe and Wise started it. The family sat on the settee in size order: Annette's mum Anna on the left, then her brother Ian, then Annette and at the other end was her sister Lisa, up past her bedtime as a treat, Mum knitted and the kids watched Saturday night telly as Eric Morecambe, the bigger one, slapped Ernie Wise, the smaller one. With no warning, Eric would tap both hands on Ernie’s shoulders and, in a flash, slap him hard on both cheeks. The shoulder tap distracted Ernie so he had no time to protect himself. It was an amazing trick that worked every time, as Annette discovered on Sunday when Ian went tap-slap on her. As soon as her cheeks stopped stinging, he’d do it again. And when she least expected it, he’d tap-slap her once more. On Monday Annette tried it out on Lisa and it worked a treat. Lisa kept laughing to stop herself crying.

One day in the summer of the hitting craze, Annette and her mum Anna were watching telly together. The telly was boring, it was the News, they were still looking for the missing girl.

‘Do you want to play a game?’ Anna asked her daughter.

‘Ok,’ said Annette.

‘Hold your hands like this.’ Anna put her hands together as if she was saying a praying, her fingers intertwined.

Annette copied the pose.

Anna gripped Annette’s wrists and said, ‘Don’t hit yourself.’ Anna’s eyes were serious, staring and unfamiliar. ‘Whatever you do, don’t hit yourself.’

Anna’s gripping hands flew upwards taking Annette’s prayer-fists up too. Boof! Annette hit herself hard on the chin.

‘Why did you hit yourself?’ demanded Anna. ‘Try again, try really hard. Remember, do not hit yourself.’

Annette braced herself, but it made no difference.

Boof!

And boof again.

The familiar Anna was back. A usual mum again. She looked sad. ‘Grannie Annie, used to play this game with me. She wanted to toughen me up so I’d stand up for myself.’ Anna reached out to stroke Annette’s hair.

Annette flinched.

‘It never worked,’ said Anna looking sadder still.

Annette tried out the hit-yourself game on Lisa. She only did one boof. It wasn’t a fun game.

After that, Annette belatedly joined in the Chinese burn craze. In her bedroom she rolled up her sleeve, pointed her two fingers into a gun-shape, licked these fingers, and thwacked them down on her own bared wrist. She liked the sting. And the red mark. And liked watching how the mark, like the crazes, faded away.

MY MISSPENT YOUTH

‘There you go, Maureen. Not as young as I once was!’

Mr ‘O Patrick set down her cases on the dirty lino.

Red in the face after climbing twenty flights of stairs.

Damp patches under the arms, belly fit to burst his purple shirt.

‘You’re only as old as you feel!’

Maureen leaning in to hug the boys and Josie.

‘Steady!’

The change in her. The eyebrows now arched in faux surprise. Like she’d only just discovered she was the mother to three kids.

Josie unable to tear her eyes away.

Little Callum studying her hard, thumb in mouth.

‘Where’s Mammy?’

They had just returned from a week in Latvia, Josie, left in charge of her two younger brothers.

Mr O’Patrick’s treat.

‘Help your Mam get over it, Josie. It’s been a year now.

She’s old enough. Twelve going on sixteen, she is, Maureen.

Quite the young lady.’

His eyes running over Josie like hands.

Mr O’Patrick, now man of the house, hard to resist.

Time stood still. Mam’s presence lingered in the flat. Je Reviens

They skipped school, watched movies.

The three of them tucked up on the settee.

Josie careful as to what they saw. The Lion King. A favourite.

Hiding under the blanket, the three of them.

Scared and safe all at once.

Evil Scar, Rafiki comforting Nala.

‘Simba still lives, infinite, in you.’

Sean’s asking ‘What’s infinite? ‘

Josie hugging them closer.

‘We are.’

The Circle of Life.

No bed-time, no getting up time. Cheese sandwiches breakfast lunch and dinner.

There was a pie one day.

The boys, (butter wouldn’t melt), perfect decoys. On cue, felling a tower of toilet rolls at the supermarket exit.

And now?

‘How do I really look, Josie?’

Mam’s doll face in the cracked mirror.

‘Not a day over twenty, Mam. ‘

(Hello stranger).

Clinging the lie. Mam saying:

‘May the good Lord take a liking to me – but not too soon.’

Though there was Mr O’Patrick to be considered when it came to liking.

Telling Josie stories of his athletic prowess as a boy.

‘A sure contender for the Olympics - if it hadn’t been for the flatness of me feet.’

Josie couldn’t imagine him young.

So unlike Da. His innocent delight.

They never mentioned him. Which made him more alive, is presence felt.

Da had loved what he called the fillims. Taking Josie to see On the Waterfront. Her suddenly all grown up. Disappointed it was in black and white, but what a story!

‘I could have been someone.’

Electricity pulsing between them, Da squeezing her hand in the dark.

Da worked for Mr O’Patrick.

On the side, like.

Then one day he disappeared.

Mam stalled the bailiffs.

Urgent family business in Ireland, you know.

Mr O’Patrick winked at Josie.

‘At Her Majesty’s pleasure, more like.’

Now Mam cried all the time.

Until Da returned. Him working all hours for Mr O’Patrick.

‘Debts to pay.’

That last time.

Da’s kiss on Josie’s head, in passing.

Why hadn’t she looked up?

Too busy, posting selfies. Balcony shots, blue sky.

Majorca?

‘Living the life!’ (Heart emojis.)

A knock at the door.

The police.

Lilies, stiff as wax on top of the coffin.

Was he really in there?

Josie pressing her ear to the polished wood.

‘Talk to me.

A word?’

Mr O’Patrick paid for Da’s funeral.

‘Taken from us too young, Maureen.’

He’d cornered Josie at the Wake.

Stuck his tongue in her mouth when no one was looking.

Delivered the eulogy.

Topic; Da’s misspent youth. Mam fifteen, pregnant. Elopement. London.

The downward spiral.

Lessons to learn.

Not Da’s stories of a childhood by the sea in Cork.

‘We had a grand old time of it, Josie’.

Mr O’Patrick stayed over now. Josie slept with the light on.

One night, a meaty hand interfering under the duvet.

Was it her, screaming?

Mam in her nightie.

Wild.

Pans flying.

‘Mind you don’t hit the door with your arse on the way out!’

The social services visiting.

Now they all went to school. Mam included. Dinner lady. A meal on the table.

A regular life.

Mam’s face,her own again. Lines etching when she smiled.

Squeezed between them on the sofa of an evening showing them an album of photos.

‘So young! Innocents abroad.

‘We were, weren’t we? What did we know?

Everything and nothing.’

Josie’s homework assignment - ‘Youth is wasted on the young.’ Discuss.

Her essay short and to the point:

‘Is there a choice in the matter? Discuss.’

SOMETHING IN THE WATER

The three boys stood in a tight huddle under the bridge, staring intently at something in the water.

Perhaps it was one of the brook’s few fish. Emma had never been fond of them, translucent and bug-eyed as they flashed against bare ankles and struggled vainly against being scooped up into jars. Oliver had even tried to build a river in the garden for one of them, spending all day digging a rough channel into the grass that ran in a ring, an inch deep at most, all but ensuring the thing spent its last days choking on mud in pained confusion.

‘What are they doing under there?’ Marjorie set down her beer. It scraped against the damp stone, dislodging a minuscule red spider that ran into the nearest crevice. ‘It’s never good when they’re this quiet.’

‘Yeah.’ Emma’s throat was dry. She picked up one of the cheese and tomato sandwiches balanced precariously on the stone, the food and drink inches from the sluggish brown water. ‘Never good.’

‘Remember the frog?’

That tiny thing, breathing with its whole body as its severed leg twitched a few feet away. ‘Don’t make me remember it.’

This was the last picnic before school, before uniforms and new friends and the gradual stripping away of this, the innocence that clung to their boys now like the droplets of water shimmering on Oliver’s knees. Nothing in life was certain apart from changes of this kind, sad ones, so when the sun came out today and Marjorie called saying come, the water will be warm, Emma knew she should do it despite her headache and the full laundry basket and the feeling, irrational but nagging like a bad tooth, that choosing idleness today was unwise.

Oliver bent down. Marjorie’s sons clustered around him, silent.

‘It could be flowers again.’ Emma swallowed the sandwich and forced a smile. She shouldn’t sound so defensive. ‘Do you remember that?’

‘The bouquet?’ Marjorie closed her eyes, smiling. ‘God, they were sweet.’

Who knew why the flowers had been floating there that afternoon? Marjorie had always maintained they were due to a spurned lover, a supermarket bouquet chucked in a fit of passion, but to Emma the source was unimportant. What mattered was the joy of their discovery; the boys had been small then, too small to have learned that they weren’t supposed to find beauty in daffodils and damp purple irises. They had swum and played and thrown the flowers up in shining arcs, taken fistfuls of dripping petals to make crowns.

Wonder. Such wonder in their faces as they played with the flowers, and such wonder as they looked down at the dying frog. Innocent then and innocent now; how frightening innocence was.

One never knew, when looking at one’s child, if the next moment was going to be full of wonder or horror. They were so very capable of both.

‘Have they found something in the water?’ Marjorie craned her neck. ‘I can’t see.’

‘It looks like it. Maybe a fish?’

‘I hope so. God forbid it’s an injured bird, or some other animal that’s fallen in.’

Oliver had scared Emma once, just after Lacy had been born. He had a cold that week, a brutal one that left him scarlet-cheeked and covered in snail-smears of mucus, so Emma had sat him down and told him very seriously that he couldn’t play with his sister, couldn’t even touch Lacy until he was better, because if he did Lacy would get very sick and have to go back to hospital. And Oliver had nodded solemnly, had understood completely—which meant that when Emma discovered him crouched in Lacy’s cot that afternoon, coughing onto the baby’s face again and again, she couldn’t pretend to herself or anyone else that her son didn’t know exactly what he was doing and why.

‘Oh, God.’ Marjorie stood, brushing the crumbs off of her jeans. ‘They’re coming out.’

I don’t want a sister. An innocent, dreadful answer from Oliver upon questioning. She can go back.

‘Mummy.’ Oliver climbed onto the stone. His face was wet, his eyes like stars as he held out his hands. ‘Look. Look.’

GIOVINEZZA

Linda McCall Ricci

Ernesta woke to the sound of a commotion in the street below. People were running and shouting, calling out names, pounding on doors. A cold surge of fear swept through her body as she pulled the threadbare blanket over her face in dread. “Oh dio mio, not again!” she thought. Only two months ago, the whole neighbourhood had been roused before dawn by the clamour of Nazi troops storming into the Roman suburb. Lorries had come thundering down Via Tuscolana, German soldiers marching in strict unison, their jackboots hammering against the pavement, shouts of “Raus! Raus! Everybody out!” echoing through the streets.

It was still very early, but the midsummer sun had already begun to rise and was threading its rays through the slats of the green shutters, casting a stripy shadow on the wall of her bedroom. It reminded her of the shuttered hall where they used to hold Fascist Saturdays when Mussolini was still in power. All the youngsters had to attend back then for the obligatory gymnastics and singing of anthems. “Giovinezza, giovinezza, primavera di bellezza…”, they would bellow out as if their lives depended on it. “Nel fascismo è la salvezza della nostra libertà”,

“Youth, youth, spring of beauty, in fascism is the salvation of our liberty”.

“Hmm, so much for that!” thought Ernesta, turning the words over in her mind and curling up in tense anticipation of whatever was about to happen. But as she listened more carefully to the noise from outside, she was hardly able to believe what she was hearing. No, these were not German voices. There was no hostility in them. These people were locals. And, incredibly, they were laughing!

Leaping out of bed, she flung on her cotton shift dress and shuffled barefoot into the kitchen to see if anyone else was up. She found her mother there holding in her arms the youngest of her siblings, just two years old, his belly swollen and distended from malnutrition, his arms and legs dangling like fine threads of yarn. Also out of bed and positioned, as he always was these days, right in front of the stove, was her middle brother, the nine-year-old Luciano.

“How come…?” the boy was saying without looking away from the stove. “How come the other kids, they get to eat “mortadella” and lovely fresh “rosetta” bread rolls every day of the week, while all we get here is watered-down minestrone?” Luciano had got into the habit of spending hours on end staring at the stove, his big brown eyes fixed intently upon it, every now and again licking his lips as if savouring the dishes he imagined it was being used to prepare, sumptuous feasts conjured up in his mind, food he had never seen, let alone tasted.

“Eh, how come?”

“What on earth are you talking about?” his mother snapped.

“They told me, Mamma”, he said. “They told me it was a whole “mortadella” sausage, this big!” He stretched his arms wide to demonstrate. “They said they gobbled it all down and were so full they couldn’t eat another bite.”

“Oh, you silly boy! They’re just pulling your leg. Believe me, “figlio mio”, nobody has seen a “mortadella” of any shape or size in these parts since ‘39!” she scoffed.

“Mamma, I think something’s happened,” Ernesta interrupted. “There were people cheering down in Via Tuscolana. Did you not hear them?” The kitchen looked onto a courtyard, so the sounds from the street had not reached her mother’s ears. At that instant, her older brother Carmelo came rushing into the room, out of breath and talking thirteen to the dozen. He too had heard the laughter and had been up onto the rooftop balcony to see what was happening further down the road.

“They’ve gone!” he shrieked. “The Germans have gone! It’s over! They’re coming to liberate us!” Their mother made the Sign of the Cross and kissed the limply slumped head of the underfed baby on her arm. “There are hundreds of people heading down Via Tuscolana, Mamma. It must mean that the allied armies are on their way up from the South. That must be why everyone is going that way. It has to be!” With that, he lifted his sister up off the ground and spun her about in a full circle. “You see, Ernesta? We did it!”

Ernesta and Carmelo did not ask their mother’s permission to go and join the crowds but simply slipped out of the apartment while she was still busy teasing the hungry Luciano. “Mortadella indeed!” they heard her mock.

FOR ONE LAST TIME

This was it. She thought. The brand-new dentures made of the purest Mother of pearl had arrived that morning. They sparkled like a diamond tiara. The new claimant would arrive by new moon.

For one last time, she picked her dentures. Years had dented them slightly. It was hard to tell that once upon a time, these dentures too lit up like giant diamond drops.

She cleaned them religiously using an ointment made of age-old herbs and a cloth napkin woven by 15 weaver girls from a village in the far south of India.

For one last time, she ran her fingers over every dent, every memory. She thought of all the lusty young men that had fallen victim to her fake teeth. Their warm hands cupping her ice-cold cheeks, their lips moist, and their eyes bright and eager as they followed her to the hollow of the tree where she lived. Later, after she had had her fill, they would lie cold and lifeless on the forest pathway until Mother Nature claimed what was hers.

Today, those memories made her sad. She knew her time had passed; even her milk-white sari no longer caressed her curves and her thick black hair no longer remained so without her many herbal oils. She held her temples and closed her eyes when from a distance she heard the howl of a wolf.

She hobbled out of the hollow of the tree into the forest, and up in the sky, a big white moon bloomed. From far she spotted a silhouette of what looked like a man.

For one last time, she wanted to feel their sweaty hands around her and their warm blood slide down her throat.

The tree, too, had stirred to life. Trinkets of white Alstonia flowers dangled from its leaves; its heady smoky smell filled the air. She took a deep long breath, slid her tongue over her dentures to check if they were in place, and adjusted her sari. She was ready for the hunt.

FRUIT

He remained in bed. He lay motionless and listened to the sounds that came from the adjacent kitchen. The babble of the water running through the coffeemaker, the scratch of a lighter, igniting the gas stove. He recognized the opening of the French window and felt fresh air wafting up to his bed. He heard the neighbors on the street, greeting each other. Their soft consonants making him wonder if it was the same language he spoke at home. There was yet another lighter and the faint smell of burnt paper, just before the flame reached the tobacco. She was smoking. He pictured his aunt standing halfway in the open door, a cigarette in her right hand, the other one propped up against her elbow. Tightening her faded rose colored dressing gown as if it was not summer but early spring and still cold outside. Looking out across the backyard her gaze would not wander very far. The dark gable of the next house, a line of outgrown spruces and a low brick wall above the mossy streak of grass would close the horizon.

He drifted into sleep again. He had gone to bed on time, albeit somewhat later than the curfew his mother had left with her sister. Whenever he came to spend the vacation, his aunt would move to the couch in the living room. He then would sleep in her bed, under smooth sheets smelling of detergent. Last night though he had stayed up late. There was a second TV set in the bedroom.

Television was a different matter in this household. Much more about entertainment and less of the only occasional educational device it was at home. In the afternoon they had watched the reruns of the Olympic Games in Los Angeles from the previous night. In clear daylight, without precedent discussion. In fact, she had suggested to watch television.

That’s why he had gone to bed just a little late. It had been already shortly after dinner, that the prospect of watching television in bed had excited him more than he had been able to handle. His heart had raced when he had flipped the switch after he had said goodnight. He had held on for a minute or two, carefully making sure the volume was completely down. First, he had watched a crime show. Elderly men in beige-colored trench coats had interviewed frightened elderly women in brownish living rooms. Then he had noticed his aunt getting ready for bed and finally settling on the couch. He had waited again for a while before he slipped out of bed. When he had been sure that there was no sound from next door, he had turned up the volume a bit. He had listened again and had turned the knob further until he had been able to understand what was being said.

Later, the program had changed from detective stories and other rather family-friendly shows to a different sort of entertainment. As soon as the word “playboy” had appeared on the screen he had realized that by now he had reached the inner realms of the forbidden territory. He did not know exactly what the word meant, but he had heard his mother use it to describe the new conductor of the church choir. Her voice had been full of the resentment. A nuance he noticed whenever she talked about certain things. Things that children were told were yet beyond their comprehension. He had watched a short film which apparently had been shot at somebody’s home kitchen. A woman had been baking an apple pie. He had seen women baking apple pies before, but none of them had acted or moved in the way the woman on the screen did. She had kept smiling and waving at the camera. Halfway through the recipe she had taken off her apron under which she had not worn any clothes apart from her underpants. He did not understand why she was being told to rub some of the flour on her breasts, to push them toward the camera. He could not make out why she would be asked to so such a thing. There was no possible connection to the pie she was baking. He had not made it to the end of the program, afraid he would fall asleep with the TV still on. He had turned it off, put the set back into its original position and had gone to sleep.

YOUTH IN THE '70S.

Two lads are approaching me in the corridor outside the science lab.

“She’s got dead eyes, that one. Go on. Pretend to punch her in the face. She won’t blink”, says the tall one.

“OK”, says the short one.

I see them. It’s my party trick. I know blinking doesn’t actually help if you’re hit in the face. I appear self-reliant, aloof, disconnected. I like it like that. No-one gets to me. Taunts don’t penetrate. They’re just raindrops on a cabbage leaf.

The short one throws a play-jab at me.

“Hi Sean”, I say, and carry on walking.

“Ha. The bitch didn’t even wince”, says the tall one.

I have a cello endpin in my coat pocket. It’s about 18 inches long. If I ever really felt under threat, I’d brandish it. It’s quite blunt actually, but it would be fun to see the reaction.

Because I play the cello a lot, I don’t have finger prints as such on my left hand. Well I do on my thumb, but the other fingers are pretty calloused, from fingering the strings. I think this would be useful if I ever committed a crime and forgot my gloves. The thing is, I’d need to feel pretty angry to commit a crime, and I don’t. I don’t feel anything much, truth be told.

Mum says it’s because I’m at an age where I like Kafka and Camus and their existential philosophy. That I’ll grow out of it and not to worry.

Dad says why can’t I be more like Pangloss and see the positive and be grateful for what I have.

They’re both right. They’re both wrong.

We had a talk at school about epigenetics this week. The teacher said that trauma can be passed from one generation to the next because trauma changes the genes and then, when you’re born, you have some of those genes in you. I think that’s silly. People spend too much time overanalysing and labelling each other with syndromes and victimlike diagnoses. I keep my own counsel, thank you very much.

But there is one thing. I don’t think Dad is happy. He appears all jolly and flirty but somehow it doesn’t seem real. He never talks about his youth but I know came here on his own when he was 14, just before the war. And then he was immediately shipped to an internment camp in Canada. He’s got a scar on his neck. I don’t know how he got it. It’s safer not to ask.

If I’ve inherited the effects of Nazi hatred, then I’ll always have it lingering and there’s nothing I can do about it. And if I haven’t inherited it, then I’m just intrinsically disconnected and separate, no reason, and there’s nothing I can do about it. Isn’t that what they call a Catch 22?

I’ve got choir practice after school today. I only really go out of habit, Wednesday and Friday evenings. But this evening, if that baritone Mr Lewis comes up and strokes my back again, I’m going to pull out my endpin.

I'm fascinated by the current that runs through these stories; I can't quite pin down what it is in words, but there's a feeling here. Well done to all!

Such lovely news! Thank you for choosing my story :-) Really looking forward to reading all of these stories