Dear Readers, my dispatches will always be free and open to everyone. I am unable to use my hands and I’m writing, via dictation, with the help of my family. If you could become a paid subscriber and support me, it’d mean so much.

The flash sale will continue to the end of the month

Monthly memberships will be priced at £5.00

And yearly memberships will be priced at £50.00

If you have any questions for me, please post them in the comment section, which is open to everyone.

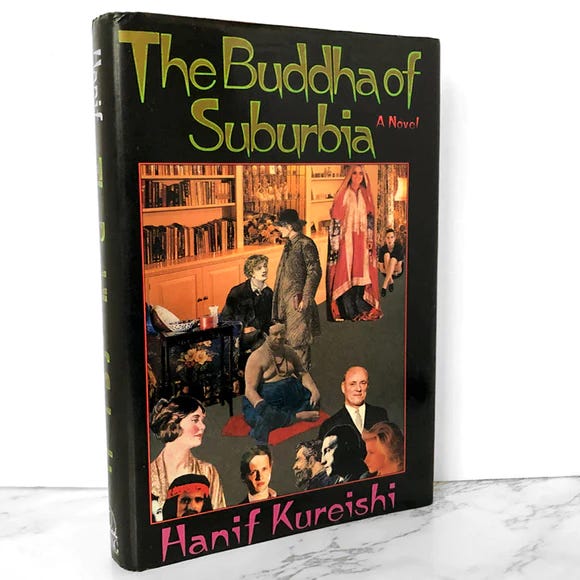

When Zadie Smith encountered The Buddha of Suburbia as a teenager, she found in its description of multiracial South London suburbs an image of her own experience. Here she remembers her first reading of the novel and describes how, on rereading it as an adult, she continues to appreciate Hanif Kureishi's sense of mischief and his depictions of race and class.

Many kinds of contraband got passed round our school: cigarettes, drugs, porn mags, video nasties, every now and then some poor fool’s diary – but books were not considered hot property. The Buddha of Suburbia changed all that. It was moving surreptitiously around our History class, it had one page folded, so that anyone who cared to could read the following line:

‘Now, Karim, I want you to put some ice up my c---. Would you mind going to the fridge?’ (ch. 13)

To see this expletive inside a book – instead of on a wall – was, in and of itself, very good value. But there was also something truly striking in seeing a name like Karim, familiar to us – though rarely seen in typeface – sitting there calmly only nine words away from the word ‘c---’. Kureishi was another familiar name; we had a Kureishi in our class (spelt with a Q), and felt we recognised the world of this novel, at least as it was depicted on the front of that first edition: the cream living room with the bad curtains, the lady in the sari, some mysterious old white people of probable renown, a lone Tory boy, a few pretty, posh English roses, and a psychedelic-looking Indian with a red headband. Word got round that there was a useful, masturbatory section depicting an orgy, somewhere around page 205 (you can go look it up now if you like; I’ll wait), and I confess I hurried down to our local WH Smith primarily for that reason. I meant to skim-read the thing, the way you skim-read Lady Chatterley’s Lover, leaping over paragraphs in search of genitals. But it was not possible to skip over those opening lines:

My name is Karim Amir, and I am an Englishman born and bred, almost. I am often considered to be a funny kind of Englishman, a new breed as it were, having emerged from two old histories. But I don’t care – Englishman I am (though not proud of it), from the South London suburbs and going somewhere. (ch.1)

This was thrilling. I had no idea you could start a book like that. In school we were reading – per the syllabus – Austen, Milton, Shakespeare, Keats, Iris Murdoch. Consequently, I thought an English sentence was a kind of cat-o'-nine tails, to be used, primarily, as a tool for whipping children into submission. I didn’t know you could speak to a reader like this, as if they were your equal – as if they were a friend. I’d had a hint of it with Holden Caulfield, but at some fundamental level Holden always remained exotic: an American prep-school kid suffering from ennui. There were Dickens’s various waifs and strays, often closer in postcode, but distant in time. Karim was different, I knew him; I recognised the way class worked in his family, the complex mix of working- and lower-middle-class realities, and all the strange gradations that can exist between these two states. And of course he was one of the ‘new-breed’, like me, like so many kids in our school, although the only other mentions of us I’d ever come across before were all of the ‘tragic mulatto’ variety. But the kids I knew were not tragic. They were like Karim: pushy, wild, charismatic, street-smart, impudent, often hilarious. Despite their relatively lowly position in the British class system they suspected they were cool, and knew they had talent and brains. They felt special, even if the rest of the world thought they were marginal. ‘Although I hated inequality’, explains Karim, ‘it didn’t mean I wanted to be treated like everyone else’ (ch. 10). Yes, exactly that. But how did he know so much about us, this Kureishi person, born in south London, 20 years earlier? Yet he knew:

Past turdy parks, past the Victorian school with outside toilets, past the numerous bomb sites which were our true playgrounds and sexual schools, and past the neat gardens and scores of front rooms containing familiar strangers and televisions shining like dying lights. (ch. 5)

He seemed to be walking through the neighbourhood. He knew the school (‘One day the woodwork teacher had a heart attack right in front of our eyes as one of the lads put another kid’s prick in a vice and started to turn the handle’. In our school, it was the kid’s head.[1]) He had certainly visited the high street: ‘They were fanatical shoppers … Shopping was to them what the rumba and singing is to Brazilians.’ (ch. 5) And he was in my house. I cringed through Eva’s pseudo Buddhist evenings; they reminded me, unfairly, of my own mother’s recent forays into sophisticated culture, especially the (perfectly innocent, I see now) attempt to gather some friends for dinner to offer them what she believed, at the time, to be sushi. Pretentious young Charlie with Keats in his pocket (‘The book was extracted and opened … Charlie imbibed a beakerful of the warm south’ (ch. 8)) reminded me of, well, pretentious young me with Keats in my pocket. As much as I laughed, at times it was painful to read, and some of the most painful details were, paradoxically, the ones that seemed invested with the most love. I owe a lot, both personally and professionally, to Kureishi’s account of the strange relationship that can exist between first generation immigrants and their children. Back in 1990 many self-serious think-pieces were being written on the subject, but none of them were more psychologically acute, or more intimate than his fictional version. ‘I like having you with me, boy’, explains Karim’s father, ‘I love you very much. We’re growing up together, we are’. (ch. 1) The child is trying to find his way through adolescence; the father is trying to find his way through a country. These two events are happening simultaneously. You’re growing up together. What a beautiful, painful way to put it.

***************************************************************************************************

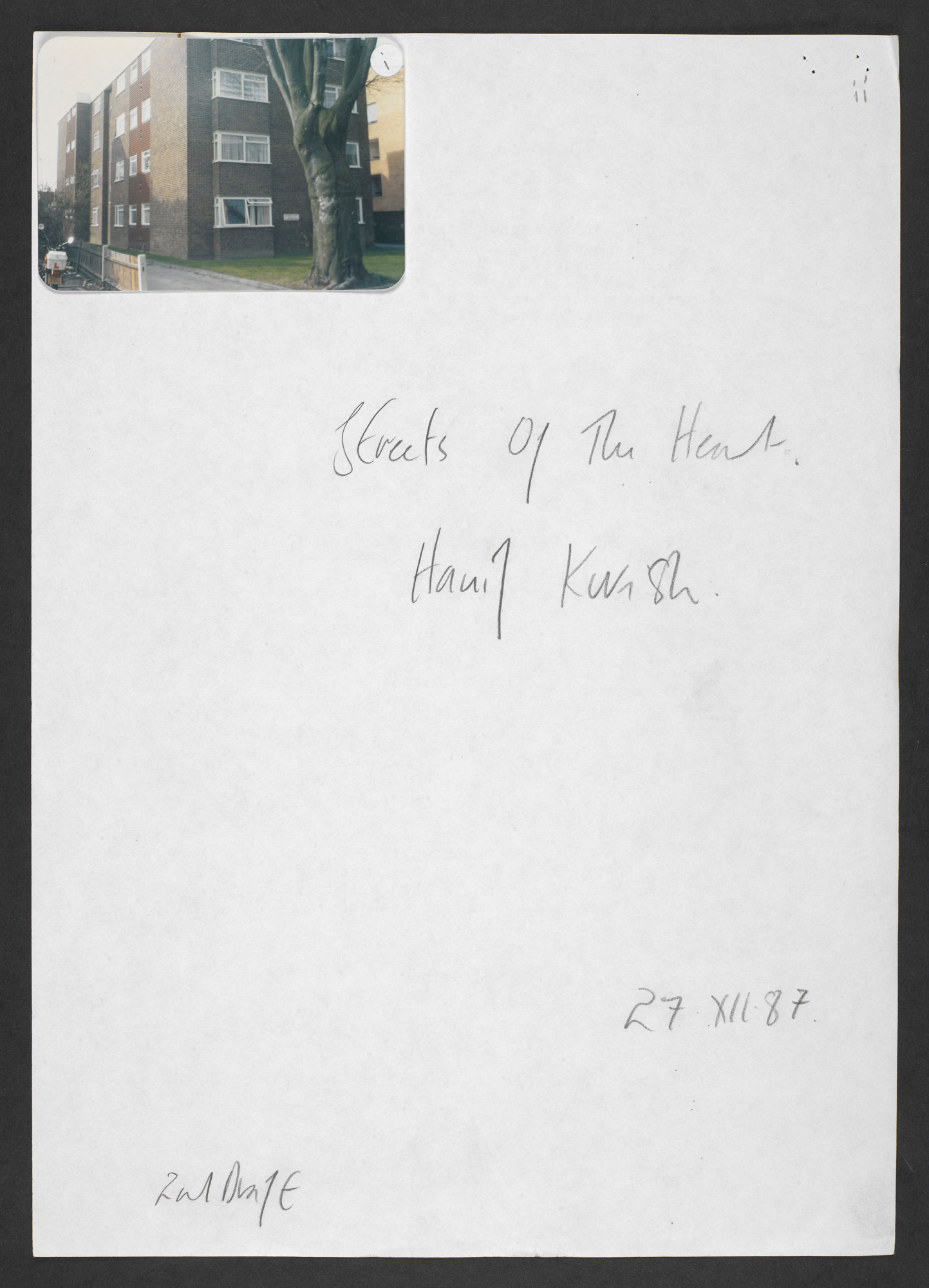

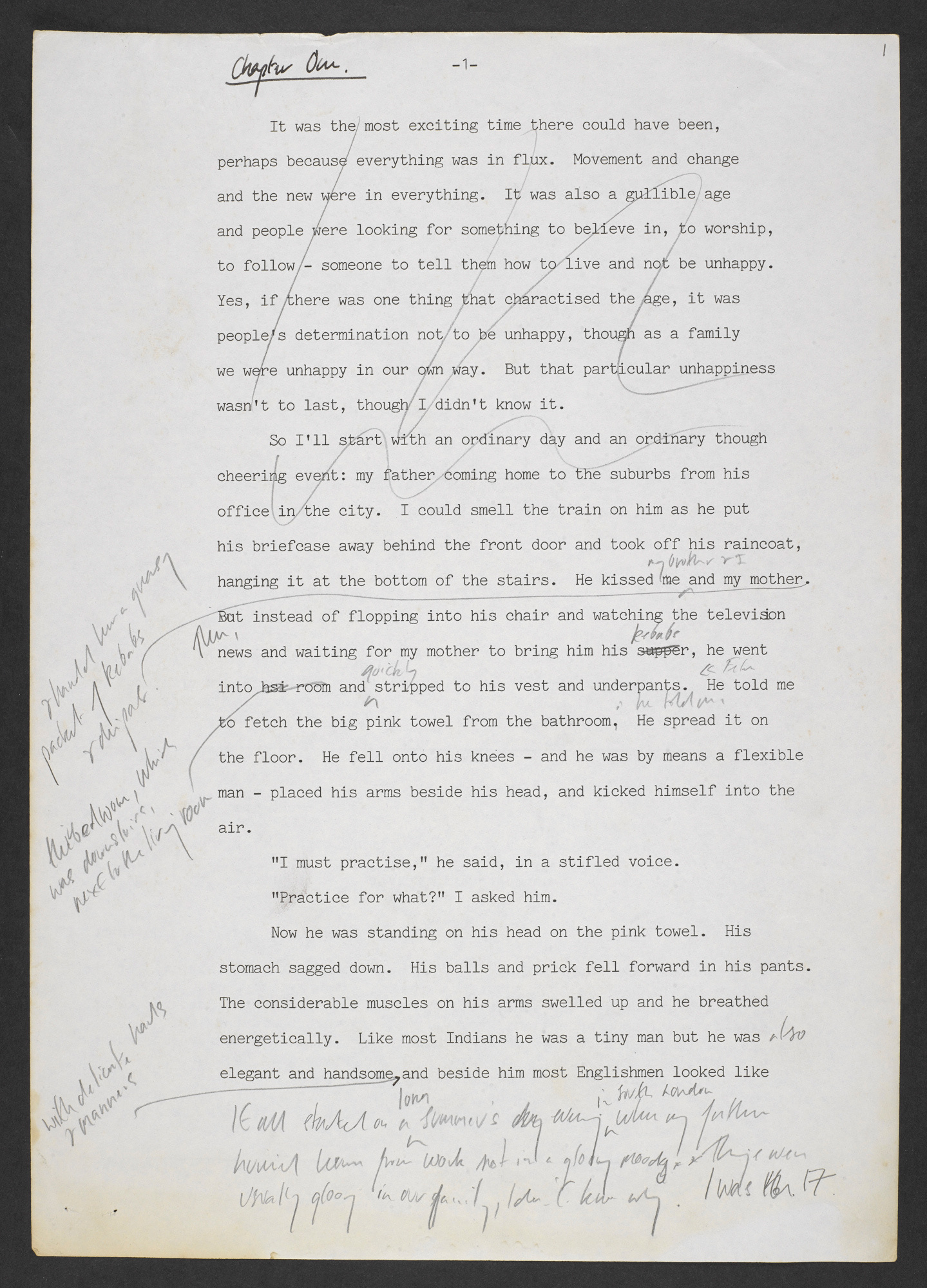

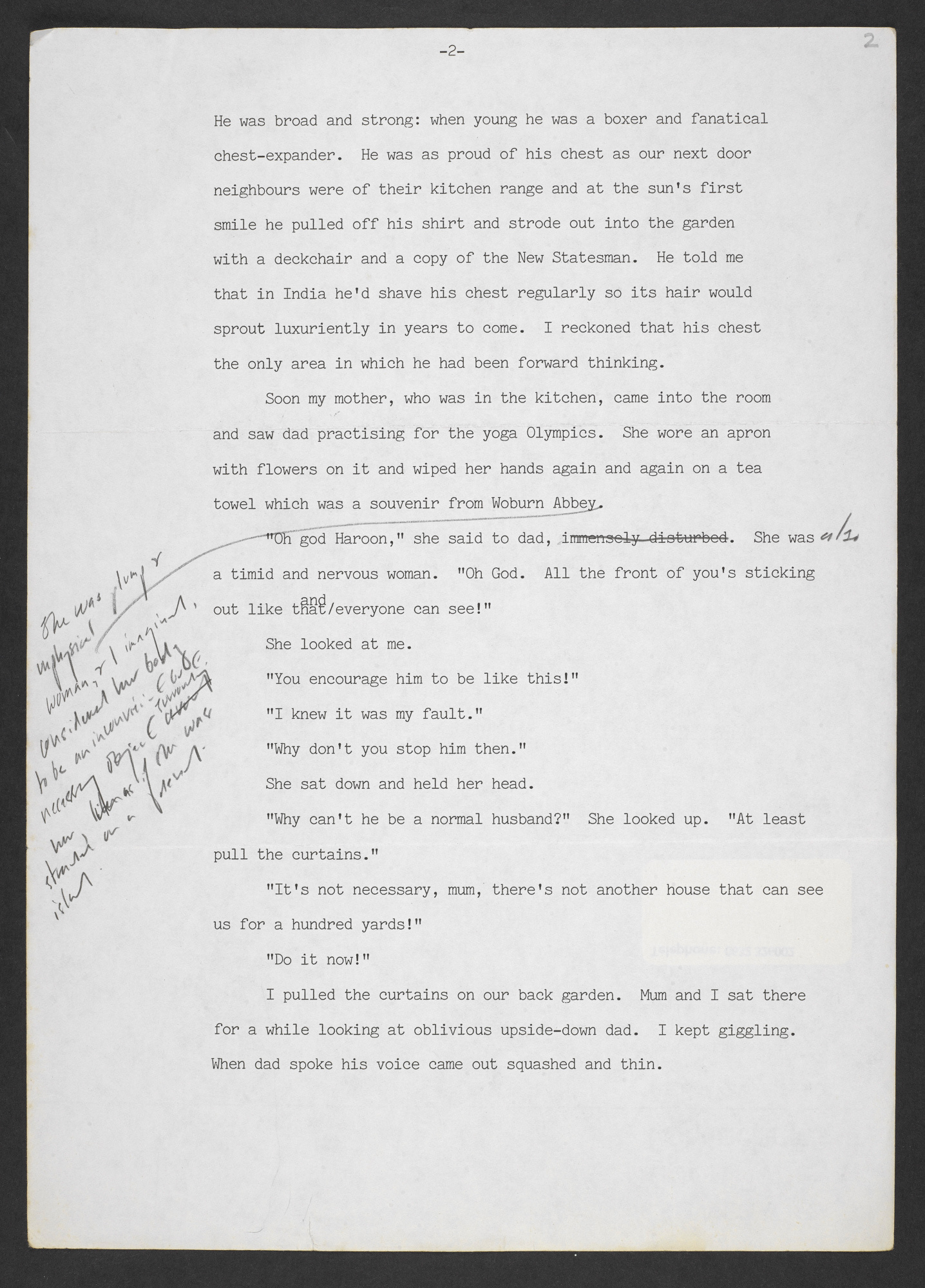

Opening paragraphs, heavily revised in Hanif Kureishi’s hand, from the second typescript draft of The Buddha of Suburbia (here titled ‘The Streets of the Heart’), 1987.

Held by: British Library

****************************************************************************************

‘The cruellest thing you can do to Kerouac’, Eva informs Karim one evening, ‘Is reread him at thirty-eight’. (ch. 1) Rereading Kureishi now, at exactly that age, I find the opposite. I get the same thrill, the same perverse pleasure, all of it made a little stronger by nostalgia. Perversity. Perversity is the central sensibility of The Buddha of Suburbia: it’s a book that refuses to toe the party line. In his role as narrator, Karim is rude where you might expect piety, fractious where you were counting on peace, and queer where it would have been far easier, at the time, to play it straight. Even the most innocuous sentences never quite end as you might expect: ‘One day Anwar made a serious mistake in the betting shop and won a lot of money’ (ch. 2). Or: ‘I was in my usual state; I had no money. Things were so desperate it had become necessary for me to work’ (ch. 14). The immigrants here are not always good and hardworking, and Karim is neither consistently right-on nor especially grateful. There is an equal opportunity policy here when it comes to bad behaviour – everyone is shown to be capable of it. Received ideas – especially about race and class – are gleefully upended in such a way as to annoy both sides of the usual debates:

Ted and Jean never called Dad by his Indian name, Haroon Amir. He was always ‘Harry’ to them, and they spoke of him as Harry to other people. It was bad enough his being an Indian in the first place, without having an awkward name too. (ch. 3)

It’s a funny idea, and familiar, now, as a comic trope – but Kureishi was the first to note it. He saw that the highest compliment a white Englishman can give himself is the assertion that he is ‘colour-blind’, by which he means that he has been able to overlook the fact of your colour – to look past it – to the ‘you’ beneath. Not content with colonising your country he now colonises your self. So, anyway, ran the new dogma, in 1990, but re-reading the novel you remember that Karim questions the blanket application of this liberal piety, too. Here he is considering his cousin Jamila’s relationship with a teacher at her school:

Jamila thought Miss Cutmore really wanted to eradicate everything that was foreign in her. ‘She spoke to my parents as if they were peasants’ Jamila said. She drove me mad by saying Miss Cutmore had colonized her, but Jamila was the strongest-willed person I’d met: no one could turn her into a colony. Anyway, I hated ungrateful people. Without Miss Cutmore, Jamila wouldn’t have even heard the word ‘colony’. ‘Miss Cutmore started you off,’ I told her. (ch. 4)

For Karim, what passes between black and white people is never quite black and white. In the case of Miss Cutmore and Jamila, it turns out colonisation and genuine education may indeed have some overlap; in the case of his white uncle and Indian father, the essentially racist concept of ‘colour-blindness’ and real human affection are able to coexist, too. Readers who prefer their ideologies delivered straight – and straight-faced – will find Buddha a frustrating read. To him the world is weird and various, comic and tragic. If this mixed reality can’t always be fully admitted while standing on soapboxes, sitting in Parliament, or marching down Whitehall, it should at least be allowed a reality in novels. There’s a sharp section of Buddha where the old argument between politics and art – the problem of ‘responsibility’ – is dramatised. Karim is an actor in a radical drama group, and has chosen, as his subject, to play a version of his own uncle, Anwar, who is on hunger-strike, for the purpose of forcing his daughter, Jamila, into an arranged marriage. Tracey, a black female actress in the group, objects to the portrayal:

‘Two things Karim,’ she said to me. ‘Anwar’s hunger-strike worries me. What you want to say hurts me. It really pains me! And I’m not sure that we should show it!’

‘Really?’

‘Yes.’ She spoke to me as if all I required was a little sense. ‘I’m afraid it shows black people –’

‘Indian people –’

‘Black and Asian people –’

‘One old Indian man –’

‘As being irrational, ridiculous, as being hysterical. And as being fanatical.’

‘Fanatical? … ‘It’s not a fanatical hunger-strike. It’s calmly intended blackmail.’ (ch. 11)

Such light, comic work is made here of several well-meaning debates of the 1980s, battlegrounds of racial categorisation and alliance, language, political responsibility. I don’t think Tracey is exactly wrong: she is trying to be responsible – but Karim is on the side of irresponsibility, and needs to be, in order to tell his story. Tracey’s arguments belong to another sphere. She may win the argument but fiction can’t be written to comply with winning arguments. Tracey continues: ‘Your picture is what white people already think of us. Why do you hate yourself and all black people so much, Karim?’ (ch. 11) It’s a familiar, crushing double admonition, and so many aspiring ‘minority’ artists have crumbled before it. The first part means, basically: ‘Don’t wash “our” dirty laundry in public’. The second: ‘For beware, if you do, you are then a self-hating _____’ (fill in the blank). Bellow was told the same thing; Roth, too. And Zora Neale Hurston. Once upon a time they even said it to Joyce, back when the Irish were thought of as a ‘minority’ rather than as a poetic stand-in for all humanity. Writers with a sense of humour seem to get these warnings more than most, perhaps because irresponsibility is an essential element of comic writing. Some, like Karim, try a high-minded argument against responsibility (‘Truth has a higher value’ (ch. 11)) and find it knocked down easily, as Tracey rightly knocks it down here, critiquing its abstract tone and specious subjectivity (‘Pah. Truth. Who defines it? What truth? It’s white truth you’re defending here’ (ch. 11)). But there is another truth, particular to writers, that in order to work with any effectiveness you will have to abandon, at least for a time, these familiar battles. If you want to create that ‘one old Indian man’, you will have to take liberties, you will have to feel free to write as you like – even if Tracey is right, even if it is irresponsible. All the great energy of Buddha comes from watching the liberty of creative freedom being taken, over and over again – as if it were a right – without too much concern for what that (perhaps entirely imagined) unified group called ‘white people’ will think about it.

****************************************************************************************

In the memory, Buddha is a lot about race. In the rereading it’s actually far more concerned with what Karim’s director, Pyke, calls ‘the only subject there is in England’ (ch. 1) – class. Again, right and left get an equal satirical poke. To his fellow actor – and committed Marxist – Terry, Karim has this to say: ‘I wanted to tell him that the proletariat of the suburbs did have a strong class feeling. It was virulent and hate-filled and directed entirely at the people beneath them’ (ch. 12). On a posh girl called Eleanor, also from the group: ‘She always did whatever occurred to her, which was, admittedly, not difficult for someone in her position, coming from a background where the risk of failure was minimal; in fact, you had to work hard to fail in her world’. My favourite example is when Boyd, another white actor in the group, who has watched Karim’s rise through the ranks, falls into a well of self-pity and spite: ‘If I weren’t white and middle class I’d have been in Pyke’s show now. Obviously mere talent gets you nowhere these days. Only the disadvantaged are going to succeed in seventies’ England’ (ch. 10). When I first read this, in 1990, it seemed to be absurdist parody. Twenty-five years later we can read similar sentiments all day long on the Internet, as armies of Boyds gather under any article online concerning brown-skinned artists of any kind. Here – as in so many matters of English life – Kureishi has proved a kind of seer. And hugely influential for a generation of writers, me included, of course. What he gave us most of all was a sense of irresponsibility, of freedom, in the smallest things as well as the biggest:

Auntie Jean really knew how to give you frightening looks, so much so that I found myself struggling to suppress a fart that needed to be free. ... But it was no use. The naughty fart bubbled gaily out of me. (ch. 3)

This is a naughty, bubbly book. It says things frankly and with delight. Nothing is agonising to Karim, really – not race, class or sex – it’s all interesting, it’s all worth talking about, without shame, and without making heavy weather of it either:

It was unusual, I knew, the way I wanted to sleep with boys as well as girls. I liked strong bodies and the backs of boy’s necks. I liked being handled by men, their fists pulling me; and I liked objects – the end of brushes, pens, fingers – up my arse. But I liked c---- and breasts, all of women’s softness, long smooth legs and the way women dressed. I felt it would be heart-breaking to have to choose one or the other, like having to decide between The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. (ch. 4)

It’s all a little naughty – but is it nice? The novel itself is preoccupied with the question. ‘I thought about the difference between the interesting people and the nice people’, writes Karim, ‘And how they can’t always be identical’ (ch. 7). When it comes to writing and acting Karim is concerned not only with the political risk (which might, as Jamila puts it, ‘expose our culture as being ridiculous and our people as old-fashioned, extreme and narrow-minded’ (ch. 5)) but of the personal risk, which – as every novelist knows – involves hurting the people you love. The Buddha of Suburbia is, among other things, a first novel and a Bildungsroman, and that form usually plays fast and loose with authorial experience. Real uncles and aunts are combined into one paper person, siblings change sex, living parents die, and so on. For his part, Karim stridently defends his right to base a dramatic character on his brother-in-law, Changez, but he also – perhaps not entirely consciously – reveals the deep psychological peculiarity that compels him to do so:

There were few jobs I relished as much as the invention of Changez/Tariq … I uncovered notions, connections, initiatives I didn’t even know were present in my mind. I became more energetic and alive as I brushed in new colours and shades. I worked regularly and kept a journal; I saw that creation was an accretive process which couldn’t be hurried, and which involved patience and, primarily, love. I felt more solid myself, and not as if my mind were just a kind of cinema for myriad impressions and emotions to flicker through [my italics]. (ch. 14)

It’s what actors and writers are said to have in common: this personal sense of immateriality that becomes, perversely, more solid when they pretend to be someone else. Karim notices this tendency himself early on, long before he is an actor, in his sexual passion for his own stepbrother, Charlie:

My love for him was unusual as love goes: it was not generous. I admired him more than anyone but I didn’t wish him well. It was that I preferred him to me and wanted to be him. I coveted his talents, face, style. I wanted to wake up with them all transferred to me. (ch. 1)

It’s not nice. But it is interesting. And funny. In Buddha, cruelty, humour and affection work hand in hand to make character, and even the smallest walk-on part is brought to sharp, momentary life by means of this potent mixture. I love Karim’s poor uncle Ted, DIY genius and clinical depressive, and the way Kureishi makes us cares for him, and laugh at him, in the space of a paragraph:

He can talk and work at the same time, can’t he?’ said Dad as Ted, sometimes in tears, inserted rawl-plugs into brick – as he made a shelf for Dad’s Oriental books, or sanded a door, or tiled the bathroom in exchange for dad listening to him from an aluminium garden chair. ‘Don’t commit suicide until you’ve finished that floor, Ted,’ he’d say. (ch. 3)

At the time Kureishi’s first novel was celebrated for possessing the same punk spirit that the novel itself documents, but there are many quieter moments too, of elegant and beautiful prose, which rereading reveals. Here is Karim on his mother, whose one outlet from domestic drudgery is her sketching: ‘Her mind had turned to glass, and all life slid from its sheer aspect. I asked her to draw me’ (ch. 7). That could be Woolf. And this could be Forster: ‘So this was London at last, and nothing gave me more pleasure than strolling around my new possession all day. London seemed like a house with five thousand rooms, all different; the kick was to work out how they connected, and eventually walk through all of them’ (ch. 9). Karim is making the new out of the old. Keats and Shelley and Donne are nestled in these pages, and the shadow of Kipling, and the even longer shadow of Dickens. Karim’s own new angle is that he’s, well, Karim: he’s got a different walk, a different talk, a fresh sensibility. He knows perfectly well he’s the kind of kid never before seen beneath the covers of an English novel, and like any smart-arse kid from the suburbs he’s going to use that and everything else. When he finds himself cast as Mowgli in his first big role, he knows it’s ludicrous – but it’s still a break. ‘I’ve found my little Mowgli at last’, says the director:

‘An unknown actor, just right and ready to break through … Isn’t he terrific?’ The two women examined me. I was just perfect. I’d done it. I’d got the job. (ch. 9)

The job of course, is the job of the exotic. But like Bellow, Roth, Hurston and Joyce before him, Kureishi sees, in this role, more comedy – and opportunity – than tragedy. Karim is nobody’s victim. And though it is certainly often tiring and usually offensive when people mistake you for such cultural types as the ‘Comical Urban Jew’ or ‘Soulful Black Woman’ or ‘Mystic Indian’, Kureishi’s point in Buddha is that it can also be very amusing. From the point of view of our 21st-century world, where the only possible reaction to anything seems to be outraged offence, I find it a relief to go back to more innocent days and remember a time when we were not all such delicate flowers that every man’s casual idiocy had the awesome power to offend us to our very cores. ‘To be truly free’, argues Karim, ‘we had to free ourselves of all bitterness and resentment, too. How was this possible when bitterness and resentment were generated afresh every day?’ (ch. 15) In Buddha this remains an open and unanswered question, for Karim is both free and not free at the same time. For him England is, in so many ways, impossible – but it is also his playground. Both versions of his experience are true. That is the great discomfort and irresponsible charm of this lovely, funny, honest novel.

The agreed 3,500 word extract from the introduction to The Buddha of Suburbia by Zadie Smith. Published by Daber Modern Classics, 2015. Copyright © Zadie Smith. Reproduced by permission of the author c/o Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd., 20 Powis Mews, London W11 1JN

I am little envious that Smith got to experience a convergence of literary filth and teenage hormones, sufficient to generate an updraught that was capable of carrying a book from horny teenager to horny teenager in her peer group. That kind of heat generates sparks, and sparks can take you anywhere.

I attended a violent comprehensive school where reading was not prized. Looking back, it is astonishing what a cultural desert it was. Where you might expect allegiances to form around bands or football teams, there was instead a bannerless tribalism, crumb-fed on fragments of pornography of the pictorial variety, and later in the form of a primitive gif file of a woman performing oral sex, that would crash the school computer network whenever it was run. We were brutes. It is a miracle that our floor-dragging knuckles overcame their own friction and gained a semblance of altitude.

From the perspective of a white, British man, my experience of this book was obviously very different from Smith's. She saw elements of her own life reflected in the novel.

For me, this was my first insight into a world that I had long coexisted with, but knew absolutely nothing about. The Asian kids at my junior school tended to be studious and insular; smart enough to pass the 11+ and vanish over the educational horizon. My interactions with the Pakistani community in my home town began and ended at a newsagents, close to my home, that would open on Sundays in a time when nothing else did. I would go in there sometimes to buy sweets.

My staggered discovery of The Buddha of Suburbia began with the David Bowie song, then the TV drama, then the book. It was a while before I made the connection with My Beautiful Launderette and Sammy and Rosie Get Laid, which I loved, and which had Roland Gift from Fine Young Cannibals in it.

'In Search of Genitals' could easily be the title of a Victorian travelogue. The account of a bespectacled, sandy-haired English missionary, who has fallen foul of a practical joke played on him by a malevolent translator:

“Another day where I hoped to catch a glimpse of the girthy palace spire, that I am told occupies the absolute centre of the city of Genitals. My guide blames sandstorms to the east. He assures me that, by the week's end, I will surely lay eyes upon Genitals, and be the first Englishman to do so in many centuries...”

A great book and great analysis by Zadie.